Legacies

What Does a Multigenerational Mixed-Race Family Look Like?

As biracial people, my husband and I should know how to raise a mixed-race child. But I find myself wondering just how much I’ve figured out.

Speak of the Dead: Seeking the Stories of My Refugee Family

The first generation of refugees have the power of selective memory. Children like me learned early to tiptoe around our families and their traumas.

“The Community Is Hurting”: Why We Need to Talk About Colorism and Bias in Asian American Communities

It feels jarring to deal with “model minority” stereotypes in non-Asian American spaces while facing negative stereotypes within some Asian ones.

Losing Whiteness When You Lose Your Father

To lose whiteness is to compress the white half, to describe it awkwardly, to never know how to address it.

I Defend Survivors to Keep My Grandfather’s Legacy Alive

If my grandfather could remain optimistic into his eighties, then how could I let myself become jaded in my twenties?

I Wanted to Know Why the Ocean Ate My Grandfather

As a child of many cultures, I wasn’t sure I could lay claim to one. But I learned that identity can grow and stretch, widen and encompass more than a single country or language.

Our Mothers’ Violence and What’s Left After

Our mothers wanted to protect us. So they hid us, beat us for having opinions, for being too inquisitive in a world that doesn’t permit girls to be curious about things.

What Is Common, What Is Rare: Why Extraordinary Events Cannot Eclipse Everyday Racism

We’d denounce the marches and torches and chants. When that moment passed, we’d continue to live with the ghosts of our country’s peculiar legacy.

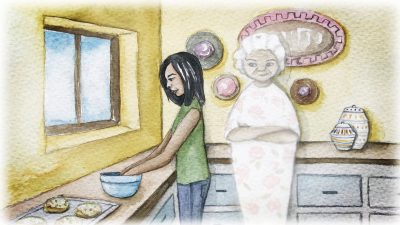

I Named My Daughter After the Woman I Wish She Could Have Met

Something unexpected cracks me open every year: Tonight, it was my daughter, recognizing the name I’d given her because I couldn’t give her the woman herself.

Unheard Grief, Unmovable Men: How an Old Mexican Folktale Speaks to Our Pain Today

All the wrong people are crying, and all the people who ought to feel something do not.