Science

My Own Personal Contagion

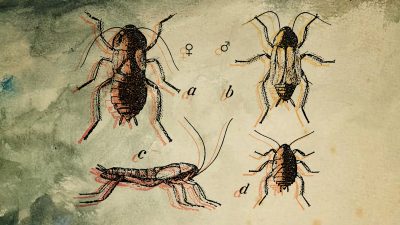

My German cockroach infestation, almost too good a pandemic allegory, forced me to confront the question of how much I could bear from New York City.

Finding God in Science

The grounding I felt in organized religion was substantial: the loss, acutely painful. I found temporary relief in all the ways nature found me wherever I lived.

Finding Biodiversity (and Chocolate) in the Forests of Ecuador

As a person who spends a lot of her time reading, writing, and teaching about endangered creatures and environments, I craved something hopeful.

Gathering Visions of the End of the World

Everyone talks about sea levels and temperatures rising, but there’s also the more tangible inevitability of the soil running out.

How Translating Annie Dillard Helps Me Attend to a Dying World

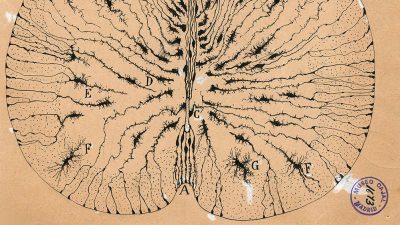

Dillard stalked a world just beginning its freefall into an unprecedented amount of change, and her response was to look, and to look hard.

When It Comes to Climate Change, Grief Is More Useful Than Empty Nostalgia

We are already living in a changed world. Giving yourself time and space to grieve is important. But grief can also be a powerful tool for motivation.

Exploring a Rocky Mountain Glacier in the Space Between Science and Storytelling

Kate Harris writes in Lands of Lost Borders, “Explorers might be extinct, in the historic sense of the vocation, but exploring still exists, will always exist: in the basic longing to learn what in the universe we are doing here.” This is exactly how I felt working at Hilda Glacier.

Less Than 1% of Military Divers are Women—I Was One of Them

Contrary to its reputation as an extreme sport, freediving has meditative aspects.

Encountering Beauty and the Effects of Climate Change in Acadia National Park

As a child growing up in a landlocked state, I’d imagined the flock of gulls as a cloud of wings, calls sounding like laughter. Now I was struggling to grasp all that we’d lost.

On Political Change, Climate Change, and the Choice to Not Have Children

My partner and I were trying to have a baby despite our climate fears. Then Trump was elected.