Losing My Religion

Finding Salvation in Death Cab for Cutie

I needed her to tell me that it was okay to doubt, to yearn, for the lyrics in our headphones to mean something sacred—with or without God.

A Painting of Eve as a Brown Woman Brought Me Back to My Faith

When I looked at her, I simultaneously saw divinity, and myself.

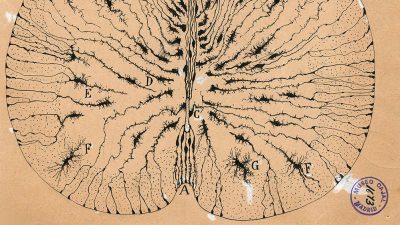

Finding God in Science

The grounding I felt in organized religion was substantial: the loss, acutely painful. I found temporary relief in all the ways nature found me wherever I lived.

My Body Is an Archive

I’ve published articles on examining the archive’s margins and gaps to recover women’s stories, but that won’t help me understand that girl who left her family when she could no longer live in shame.

Becoming My Own Woman, Without the Faith of My Childhood

I had always found a gathering of women sharing their stories and wisdom an effective way to touch the divine.

Why I Left My Orthodox Community in Buenos Aires

I spent so much time watching and trying to understand secular women that I never bothered to try to understand the others, the ones who never left.

When I Left the Cult I Was Raised In, I Learned What a Family Could Be

Spending my childhood preparing for the Apocalypse exacted a price on my ability to trust, particularly in the concept of family.

A Heathen’s Love Affair with Churches

Most of my formative adolescent experiences took place in churches, but it was never about god. What drove me was a feverish desire to belong.

True Love Waits: How “Saving Myself” Made Me Lose My Faith

To your church and to the world, there is nothing more dangerous than a woman wanting.

Glory in the Floorlamps: How the Theatre Became My Church

Both church and theatre demand from their followers the suspension of disbelief, and the ability to inhabit an imaginary set of circumstances in lieu of the known.