Family Health Parenting

How I’ve Changed as a Parent in the Wake of My Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis

On the heels of my diagnosis, I feel there is no way to construct a narrative around what’s happening to me—a deep betrayal for a writer.

For Mother’s Day, my six-year-old daughter came home from school with a questionnaire about me, a page full of sentence fragments that required her to fill in the blanks. The first: “If I could give my mother a gift, it would be ____________.” I was delighted that she knew to complete this sentence with books. The second read, “My mother likes to: ____________.” My daughter had written just one word: rest.

It’s a word I’ve never associated with myself. So much of my identity is bound up in my work as a writer, and I’ve written forty hours a week for twenty years now. I didn’t know my daughter had noticed how tired I am—nothing in her demeanor changes when I say I need to rest, or am too tired to take her somewhere. But of course she’s noticed. We reveal ourselves more than we think we do.

Since my twins were born three years ago, I’ve increasingly experienced time as quicksand. I drag myself through it, a distressing experience that’s increasingly hard to hide. My fatigue reached new heights several months ago, around the time I was diagnosed with the neurodegenerative autoimmune disorder multiple sclerosis.

I’d accumulated a number of multiple sclerosis symptoms in the year preceding my diagnosis: an icy hand on my cheek and arm that transformed into pain that spread around my eye socket, pins and needles in my feet and hands, lack of balance, vertigo, severe dizziness, difficulty emptying my bladder, difficulty paying attention, difficulty staying organized, increased irritability. Getting diagnosed was a slog that entailed the doctor ruling out other conditions and me convincing them that my strange symptoms warranted an MRI. In 2011, I had developed a brief spell of blindness, optic neuritis, and learned with alarm that it was an early warning sign for multiple sclerosis; I had a brain scan, but there were no lesions back then. When I received my diagnosis in 2019, I felt as though I’d been quietly expecting it for years.

I am a person who once had a phenomenal short-term memory; now, during a bad flare, I may travel to a destination and not remember the purpose of my errand, or need to read a page several times to remember what I read. By temperament, I’m intense and driven and sensitive, but over the last couple years I’ve felt increasingly detached from the world, as if the events that I experience are not quite real and I’m viewing them from afar through a telescope. I’ve become, relative to who I was, quick to not care about certain things because every tiny sound or move I make seems wearying, and caring as passionately as I used to care is a whole other level of commitment I can’t afford. My daughter is right: I just want to rest. But sometimes I’m sad this is how she’ll remember me.

*

My aunt, a doctor, died in Chennai from progressive multiple sclerosis when I was a child, leaving two children behind. The prognosis for most multiple sclerosis patients is much altered from what it was then, but it’s still common to become disabled toward the end, even of a normal lifespan, and remembering all that is possible is what frightens me. I remember seeing my aunt not long before she passed, observing how her fine motor skills, previously deployed to crochet intricate baby dresses, had disappeared; how she lacked the memory to hold extended conversations, her legendary intelligence no longer manifesting due to the invisible workings of her immune system—something meant to protect her that was instead destroying her nervous system. I remember her tremors, like a leaf shaking uncontrollably in a wind, and I remember wondering whether something like that could ever happen to me.

When I received my multiple sclerosis diagnosis in 2019, I felt as though I’d been quietly expecting it for years. Having seen the ravages of this illness, I am terrified in a way that people who know nothing but the term “multiple sclerosis,” and a list of symptoms associated with it, cannot be. Words cannot contain experience. I feel as though I have been handed dread, dread in the form of a timer that has been ticking without my knowledge, counting the time that is left for my mind to function as it has; the time I have to spend fully cognizant with my children—but I don’t know when the timer will go off. It’s the unpredictability that terrifies me.

For the last six months, there’s been no moment without symptoms, ever fluctuating. These symptoms are mild compared to what they could be, but it’s a struggle to retain a sense of proportion when the disease is so unpredictable; when I don’t know if I’ll be physically able to supervise a play date or whether I can take on extra work. Nowadays, in most cases, doctors can stave off lesions through infusions, but it’s likely that eventually I will be unable to work. My family financially depends on my ability to work and my clear thinking, since my income is the primary one. I wish I hadn’t already seen what this illness does, how it can leave children effectively with one parent.

I try to remember the mother I wanted to be with my children before I had any. I wanted to be the kind of mother who baked cakes for their birthday parties and arranged playdates and read to them every single night. Gifted or cursed with a big imagination, I’ve been imagining my children’s hobbies, sports events, graduations, boyfriends and girlfriends, and the birth of their children since the first days I held them. In all of those visions, I’d pictured myself as strong, healthy, and most of all being able to say something helpful. But thinking about the year I’ve had, full of fatigue and brain fog, when I can only achieve clarity with a measure of effort I’ve never before had to expend, I fear I’m not going to be that parent after all. Right now I’m not even a mother who can pay full attention as they try to learn to bowl or hit a baseball. When I go outside with them in our neighborhood, I often sink to the sidewalk to watch them playing, unable to stand for long stretches.

It will be enough of a challenge for me now, I think, to stay a mother who is kind, who helps them with their homework, who teaches them how to get along with other people and survive difficult situations. I worry there won’t be energy left over after that. I worry I might not even be up to those basic tasks. I often feel a sense of urgency around parenting now, like I can’t wait until they’re old enough to learn what I have to teach them. How much time do I have left to see my children grow up?

I often feel a sense of urgency around parenting now, like I can’t wait until they’re old enough to learn what I have to teach them. Most of the time, I can set the tick-tock , the urgency, aside. I can enjoy the evanescent moments of happiness: the delight my twins take in a chocolate buttercream frosting, the chapati doll my daughter sculpts in her own likeness, the glee of my twins as they race on their scooters, the joy my daughter finds in coding and making her own Halloween costumes. I work from home and I’m grateful to see all the ebbs and tides, the full flow of their childhoods, even if it’s through an odd prismatic lens of fatigue and telescoping vertigo. And yet there are other moments when I’m alone, working, wondering what to do with the grief I feel because my children will remember me struggling, desperately needing to rest. They might never think of me as the parent I hoped I would be.

Where do I put these feelings and fears? We live in a culture of relentless positivity and denial. People toss off, “It’s not as bad as thirty years ago,” or “Maybe it’s not multiple sclerosis?” And because of that urge to immediately try to have an answer, to comfort me, or to tell me—the person experiencing this illness—how I should see things, I live alone in a state of mourning everything I once imagined.

*

Your mind is altered with multiple sclerosis. When every thought takes more time, when your personality doesn’t feel like your own anymore, when you perceive the world so differently, life itself feels different. The old methods don’t work anymore. My experiences are contingent on something entirely outside of my control. And there’s nothing I did that caused it, nothing I could have done differently.

What I love about writing fiction is the ability to make meaning out of the events I make up, to show how one event caused another. But in the case of my own mind, there’s no meaning there; just the body doing its own thing, breaking down without my consent.

Where do I put these feelings and fears? We live in a culture of relentless positivity and denial. Parenting, of course, has been a years-long lesson in just how much is beyond our control. Children are born with temperaments and develop their own personalities and interests, strengths and limitations. Whatever we imagined for them is a pale shadow compared to their lives and how they actually unfold. But in most situations, we can also rationalize and justify and see how things fit together for our children. We get the satisfaction of choosing our response to them and what they do, and in turn we get to share ourselves, our real selves, with them. We can help them construct a narrative of their lives, a story about who they are and how they feel, and this can help them feel the world is a little safer.

In my case, the veil is off; the pretense of control, of cause-and-effect, is over. On the heels of my diagnosis, I feel like there is no way to construct a narrative around what’s happening to me, a deep betrayal for a writer. This is the part that is so challenging to explain to people: My life story now is chaos. There’s no predicting how this disease will affect my children.

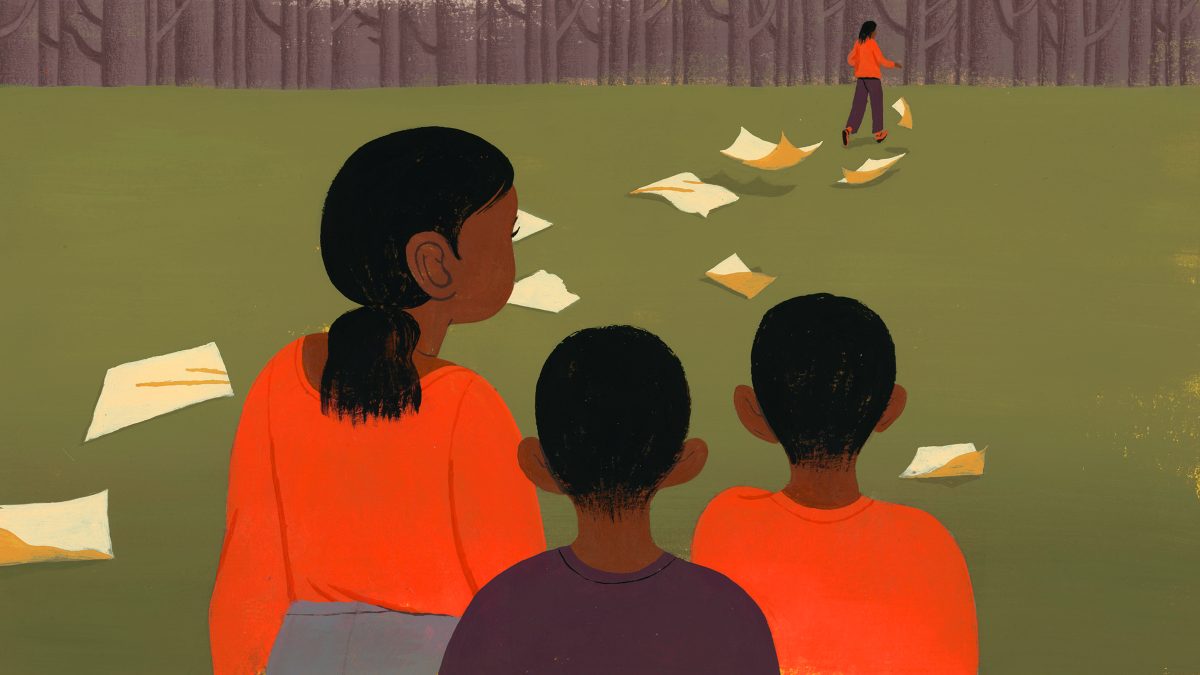

I often think of Hansel and Gretel, without their parents, wandering in the woods. Now, when I write, when I speak, when I am with my family, I am conscious of trying to lay a trail of breadcrumbs—in my writing, in our home, everywhere—for my children to find, perhaps in some future when I am not recognizable to myself. I do my best so that they will remember, but I don’t know if they will ever truly find me the way I was.