Family Adopted

The Thing About Being Gay and Adopted

“In moments like this, natural childbirth seems like magic to me.”

In the afterglow of Thanksgiving dinner, everyone’s a little drunk. A few lines of gossip float across the table—something about my cousin, who is having her third kid. My aunt plays a Facebook video of the birth announcement. We see a warmly lit living room, with my cousin on the couch in sweatpants. She hoists her younger daughter onto her lap and tells her, in the calmest voice, that she’s going to be a big sister.

“Ahem,” Mom says, looking at me with that I’m-about-to-embarrass-you face. “I want grand-child-ren.” She stretches the last word, as if it’s a punch line.

I smile reflexively. It was a joke. Moms make this joke all the time—it’s #1 in the Mom Joke Book, the joke that says I love you and I support your life choices, but I also want to make sure you keep this thing going. I laugh—or try to; I blow air through my nose in a way that could be construed as laughter. I know this feeling: the urge to fast-forward a conversation, to edit the script.

Someone across the table says, “Aww.” It’s one of my parents’ friends. Acquaintances? I’m not sure; I haven’t seen them before tonight, and I don’t think my parents have told them I’m gay. Or single. I look back at Mom. Does she not want me to comment on how inappropriate this is? Does she not understand what she’s implying?

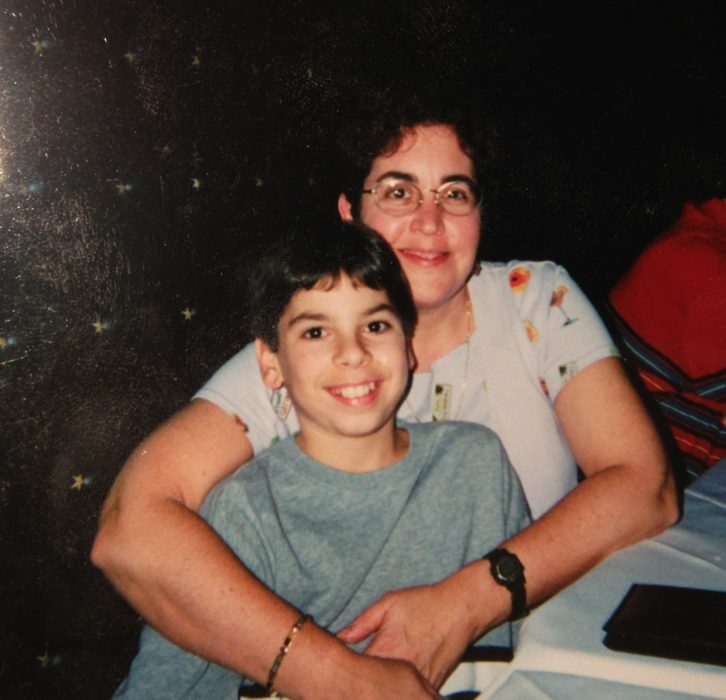

Mom taps my shoulder and brings me in for a slightly awkward—but adorable—tableside hug. I know what she’s going to say, because she always says it in semi-performative moments like this. She calls me “our gift from God,” and someone across the table (the same person, I think) says, “Aww.” I laugh and accept a turkey-greased kiss on the forehead.

*

It might be an ambiguous phrase to everyone else, but those four words—“our gift from God”—unlock a specific story in my family. My mother endured five years of infertility treatments in the mid-1980s. She still tells me stories about “life-draining” hormones. Headaches, nausea, inexplicable shoulder pain, and the emotional confusion of not knowing when—or how—she’d have a baby of her own. A week of excitement at the beginning of a new treatment, a new drug, a new clinic. A month of holding her breath and crossing her fingers, feeling superstitious in the tiniest moments—washing a dish or staring at a shadow on the ceiling before bed. And then the news, broken by doctors in low, even voices in the middle of the afternoon. The drive home, the silent dinner, tears during a commercial break in Jeopardy . Trying again. When the infertility treatments didn’t work, my parents spent the next five years shuttling between adoption agencies and attorneys, searching for a healthy American infant.

“It took us ten years to find this one,” Mom says. She messes up my hair, making it stick up a little. I pick up my coffee cup and take a sip. The cup belonged to my maternal grandmother, part of a set of heirloom dishes that only come out at Thanksgiving. White with little painted grapes. The cup feels light, thin. Breakable.

We’re sitting in the dining area of my parents’ new one-bedroom condo, and from my seat at the table I can see a few cardboard boxes half-hidden behind the couch. My parents just moved in six weeks ago. Family photos that used to spread across every bookcase and coffee table in my four-bedroom childhood home are now huddled on a few shelves. One of my baby pictures half-conceals a photo of me standing in front of a limousine on prom night. My date and I are sticking our tongues out at the camera. I was still in the closet.

Most of the other photos are the same: I’m standing in the middle of my parents. The three of us, a family. My mom always wanted a big family. Children and grandchildren and nieces and nephews, with rowdy family vacations where all the kids dribble food on themselves and the adults laugh and wipe it up.

After they adopted me, they tried a second time. I almost had a sister. We’d named her Ariel, and for a month our living room was a labyrinth of wooden furniture and baby blocks. Ariel’s mother changed her mind the day before delivery. My parents never tried to adopt again.

*

At my parents’ house, the conversation skips to dessert. My great-aunt says I must be lucky to have a mom who can cook so well. Mom starts to slice the apple cake.

In my mind, for a sliver of a second, I’m sitting at a circular table in the corner of an unfamiliar coffee shop. I’m thirty-five, maybe thirty-seven. My husband is with me, and we’re meeting a surrogate. Everyone’s trying to act nonchalant. I break the ice with a line about traffic, or how warm it is for mid-December. The surrogate tells us about her job, her commute, and the best time for her to take a break from work. We laugh generously at each other’s jokes, tiptoeing around the fact that we will have to negotiate, together, the life of a tiny new person. We know it will be hard, expensive, and emotionally complicated. We know it will continue to be hard, expensive, and emotionally complicated, probably forever. But we don’t talk about that yet. In this movie in my head, we’re just trying to enjoy our coffee.

I’ve played this clip thirty or forty times—whenever someone mentions children, family, or the future. I’m twenty-eight. Single. For now, I can’t fast-forward past that opening scene.

Which is not to say I don’t know how the movie might end, or how it might feel. I do. I feel it in my mom’s stories about clinics and doctors and hit-and-run prescriptions. I feel it in the word “gift.” I feel it in those semi-performative hugs and retellings of the decade it took my parents to get me from someone else’s family into this dining room. I feel it in unanswered questions about my birth mother and birth father—unasked questions, too, because it’s difficult to ask about something you know so little about. In a hundred tiny awkward pauses at family dinners and innocent small-talk attempts, I know exactly how it might feel.

*

Mom squeezes my hand. I drift back into the room, laughing at another family joke. The chins. Everyone on my mom’s side of the family has the same chin—boxy toward the top and rounded at the bottom. My cousin’s littlest has it, too. I don’t have that chin, though I don’t exactly not have it. Depends on how close you look.

“He’s got your eyes,” someone said in the ACME checkout line yesterday. It was a younger mom—she was standing behind us, with three toddlers tugging on her capris. In her cart were four boxes of Kix, a case of fruit roll-ups, and a small pyramid of Ziploc sandwich baggie packs.

Mom smiled and looked down at her box of stuffing mix. Small talk. A specific kind of mom-to-mom small talk, which mine has been navigating for years. Steering conversations around the jagged ridges of potentially awkward backpedaling. Wrapping ten years of trying and losing and trying again into a smile and a neighborly nod.

“He does, doesn’t he?” Mom said, half-smiling.

“Just the one?”

“Just the one. One and only.”

“I wish,” she said sarcastically, bending down to pick up one of her boys.

My parents tend not to mention my adoption in front of strangers. We look alike, ish : We all have dark hair, dark eyes, and arms that can barely reach the top cabinets in my parents’ new kitchen (we’re all on the shorter side of 5’6”). I understand not wanting to come out as an adoptive parent to a stranger in the ACME checkout line. Wanting to be normal—to buy stuffing mix without explaining the existence of your own kid.

Ten or twenty years from now, if I’m in the same position, I won’t really have a choice. A gay couple with a kid can never pretend to be conventional. In parent-teacher conferences and sleepaway camp drop-offs, emergency contact forms and supermarket checkout lines, we’ll be coming out all the time. And if we adopt—or if we find a surrogate, because there will be complications either way—we’ll need to make sure our kid feels okay. Maybe not normal, but okay.

*

The hardest thing about adoption is fitting together all the overlapping stories—biological, legal, hypothetical. Telling a coherent truth from so many asymmetrical, half-known truths.

The story was simple when I was little: Couple, seeking family, receives gift. As I got older, it splintered into sharper, more hazardous stories. My parents were always honest with me, but they also didn’t want me to feel like an afterthought. I was always their son, never their adopted son. No qualifiers or adjectives or caveats—and I’m thankful for that.

But there are some things we don’t talk about, like the implication that I might have to adopt, too. Even if I don’t, I’ll experience some version of the legal wrangling and bureaucratic energy it took to bring my parents and me together. My adoption should be proof that it’s possible. And it is possible. But it’s also confusing, exhausting, and something I’m not sure I would want to do unless I had to. Sharing my reservations about it might make my parents think that I view my adoption as problematic, somehow. My mother already worries she’s made some kind of mistake telling me too much or too little about her fertility odyssey, or glossing over some of my questions with the phrase “gift from God.” I don’t want her to regret what was always out of her control.

*

After dessert, we move to the couch. Football is on, but my aunt is passing the Facebook birth announcement video around one more time. In moments like this, natural childbirth seems like magic to me. An open highway, a straight shot to a destination I’d love to visit, but I’ve lost the map. I’m wandering through difficult conversations and cold, unfamiliar places and wondering why—God, why —it has to be this hard.

I think of the years my parents spent driving from clinic to clinic, zigzagging between possible outcomes. I think of my cousin calmly telling her daughter about a new baby. I think of my own life, and the years I could spend trying, or not trying, to become a parent. I wonder if some people are just meant to be a part of other people’s families, instead of starting their own.