People Losing My Religion

Becoming My Own Woman, Without the Faith of My Childhood

I had always found a gathering of women sharing their stories and wisdom an effective way to touch the divine.

In rural Massachusetts, those in the outside world could call us unworthy because of where we came from. But once the door was locked and the shoes were off, we could safely be Nigerians—boiling codfish for okra soup, shoveling coal into the fireplace, singing Nigerian gospel songs. This was the only Nigeria I knew. I was born and raised in the States. We didn’t have the money to stay with a doting grandma and laughing grandpa in Nigeria every year, so we pieced together a homeland of our own making.

As I grew, I learned the values of this makeshift homeland: An African is smart. An African woman takes care of the house and works. An African sings her favorite gospel songs, and—most importantly—an African prays.

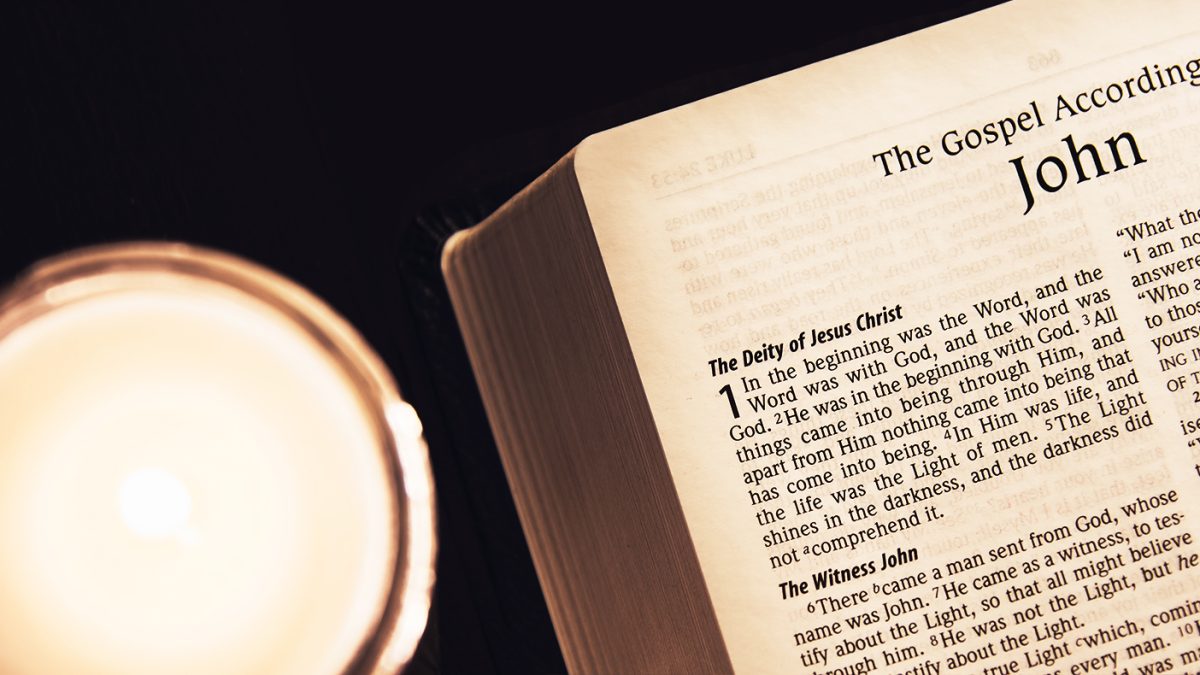

We prayed at night and in the morning, too, because that looming sense of displacement one feels when one is always on the outside gave us much to pray about. We prayed on our hands and knees, in front of a white candle and a heavy Bible. Oh God, please help us with the bills. Oh God, please change the heart of that lady in my workplace because she is terrible to me. Oh God, help our family back home. Oh God . . . It seemed that to be African, especially to be a contemporary African woman, meant not just having children, maintaining a house, and getting my PhD, but also binding myself to a supposedly merciful God who left us at the mercy of everything. When I bowed in prayer, all I could think was: How will I get free of all this?

When the God you are told to love is either a brute or woefully withdrawn from the deepest stirrings of your heart, you can become frozen to life. I’ll never forget the day my father prayed about my clothes. I was fifteen or sixteen, experiencing a rapid growth spurt and experimenting with makeup, bared midriffs, and platform shoes. One afternoon, my father stood as the mighty patriarch, doling out a prayer for everyone in the family. Finally, he got to me: “Oh God, please take away the spirit of looseness from Itoro.”

I hoped someone would speak up on my behalf. Where was my mother? I thought. But by that age, I had grown tired of wondering. Her body was there, her lips were moving, but it felt as though she had emotionally checked out. I learned another unspoken way of being from her: An African woman shuts down her emotions. Which is what I tried to do that day, too. My father might as well have been God, and if this was God’s estimation of me—that I was a loose girl who was so lost no one would speak on her behalf—then I was doomed.

I yearned for a closeness to my parents and my culture, but I also wanted a life free from denial and religious absolutism, where I could feel at peace as I truly was. If disinheriting myself was the trade-off, I wanted out. Day after day, I carried my frustrations to my bedroom, where I said prayers of my own. Oh God, if you get me out of this town and away from what I think it means to be an African, I’ll make a success of myself. Oh God, please free me from my parents—I love them, but they don’t see me. Oh God, I’m not sure of my purpose, but I know I’m not here to do this.

*

At age thirty-one, I found myself in the bustling city of Nairobi, Kenya. I had traveled there for a writing fellowship and deliberately missed my flight when it was time to leave. I enjoyed the routine I had established for myself—riding in brightly colored matatus blasting everything from Burna Boy to TLC, chatting with the women in my neighborhood salon, haggling about whether the avocado at the produce shop should be twenty or twenty-five cents.

My days in Nairobi felt peaceful and carefree, though perhaps others in my place would have worried about having no secure employment and a dwindling bank account, being a woman alone, daring to think I could make a life in Africa. I stayed and risked the simple act of feeling good because anything less felt intolerable—well-being is a kind of god, too.

One day, a friend I had met in Nairobi—I’ll call her Muthoni—asked me to join her at what she described as “a gathering for women to share and learn from one another.” I was excited, as I’d been there for four months and was still trying to make meaningful connections. I pictured something like the sister circles I’d attended during the seven years I lived in the Bay Area, with chakra cleansings and a goodie bag of healing crystals. I had never stopped believing in a higher power; I just craved a faith that accepted me as I was: someone who was lovable no matter her flaws and proclivities, who believed that skipping church service for a good brunch with friends was fine, who wasn’t getting married anytime soon. While figuring this out, I had practiced Zen Buddhism and meditation, attended nondenominational church gatherings, and tried acupuncture and reiki. I had even worked with an intuitive healer who would’ve made my parents question if the daughter they raised was becoming a witch—the worst thing a well-bred Nigerian woman can be.

I had always found a gathering of women sharing their stories and wisdom an effective way to touch the divine, and I was eager to experience a similar gathering in Nairobi. Also, I liked Muthoni. Ten years younger than I, her gentleness and quiet exuberance reminded me of myself at that age. She had an openness to the world that had not worn her down. I was happy that she had found a supportive community, and at such a young age. I told her I would go with her. “I’ll stay for an hour or so. Then I have a birthday party to attend,” I said.

I yearned for closeness to my parents and my culture, but I also wanted a life free from denial and religious absolutism.

“Sawa,” she replied—a short response capturing the ease many Kenyans harness, no matter the circumstances.

Perhaps when you are attempting to create distance between who you once were and who you hope to become, something must arise to test your resolve. Muthoni and I took two matatus to reach the gathering in the Central Business District. Then, at the last minute, the organizer texted to tell us the location had changed from a hotel to her home. “Twende!” Muthoni said, slightly exasperated. We got off one crowded bus and crammed into another. Soon we arrived at an apartment complex perched on a narrow street. “We have to go up five flights of stairs,” Muthoni told me.

“That’s fine.” We began to climb. “So, where did you meet these women?”

“Oh! At a church meeting,” she said between breaths.

“Oh. Church.” I heard my voice tighten.

“Yeah, church. Why, you don’t like church?”

It wasn’t that I didn’t like church. On the contrary, in the Bay, I had gone to many Sunday-morning nondenominational gatherings, where the preacher spoke about how Jesus was a woke and metaphysical brother; how every human carries an inner light and a voice that represents the God of our own understanding. But I suspected that what I was climbing five flights to get to was going to be more literal, and far more certain of the way to righteousness. By the time we reached the fourth floor, I felt humiliated. Here I was, this New Age hippie Westerner, thinking that a “gathering of women” meant we’d pull tarot cards together.

Instead, I had a feeling I would again find myself face to face with the God my parents worshipped. Jehovah Jireh: the one who hated looseness of spirit, the one who would wash you in the blood of the Lamb, the one who required constant sacrifice to prove your worth. The one I’d seen many Kenyans celebrate with their “God is All” bumper stickers, pictures of (white) Jesus on walls, and hymns blasting from many church speakers.

We reached the fifth floor slightly out of breath. “The group’s official name is Women of Faith,” Muthoni said, knocking on a door. “This is a prayer meeting.”

Of course it is, I thought. I had tried so hard not to live this way anymore. I had assumed I could forget how colonization and Western religion had changed the fate of an entire people. This was the legacy my parents had brought over from Nigeria, and no matter where I went, I’d always have to reckon with it. Entering this room brought me close enough to touch the wound my parents had carried and passed on to me. I could do all the mindfulness meditations I wanted; I’d still have to acknowledge what I inherited from them, and how it had shaped me, too.

I said very little as we waited for the meeting to start, mostly because I understood very little. Bits of English mixed with Swahili and Sheng (the Swahili equivalent of Spanglish spoken in Nairobi). The apartment was small, filled with the markers of a home: family pictures on the wall, comfortable couches, a coffee table where the chai and mandazis sat. Muthoni introduced me to the organizer, a woman I’ll call Sister Achieng, who was also the pastor of a congregation.

“Karibu,” Sister Achieng boomed in a rich voice fit for a preacher. She looked me over suspiciously. “I thought you were American. You look African.”

I had no energy to explain my history, so I simply bit into a mandazi and said, “I am African.”

Before she could respond, another woman handed me a mug and began pouring chai. I tried to tell her that I only needed a little—“Kidogo”— but she kept pouring. “We take large portions here,” she said, smiling. I couldn’t explain to her that milk made me bloated, and it seemed rude not to drink what had been put out, so I took a few gulps and swallowed my discomfort.

Another lady went to lock the door. “If anyone wants to come in, they’ll have to knock,” she proclaimed. “We are here to get down to business!”

The other women clapped their hands and cheered. “Yes! Getting down to the business of the Lord!”

I looked over at Muthoni, but she was deep in conversation with someone else. It was 2 p.m., and the party I’d hoped to attend started at 3:30. It was a party for a young gay man I’d met, a little older than Muthoni, who was eager to introduce me to the community he’d leaned on for support as he was trying to leave evangelical Christianity.

“Thank you, ladies, for coming to the third Women of Faith fellowship meeting,” said Sister Achieng. “We gather to hold each other in faith and prayer, because, as women, we must uplift each other in Christ when it seems impossible to hold on.” Amen s followed, with a few women clapping. “Let us stand.”

Everyone stood in a circle as another woman, whom they called the Minister of Song, began singing, and everyone joined in. At 3 p.m., when I had planned to start saying my goodbyes, the Minister of Song stopped to give a testimony. “You know, it can be so hard,” she said. The women nodded. “But what the Lord has done for me I can’t describe. I am humbled before His presence.”

The minister put her hand over her heart as the room rang with Amen s, Yes es, and Hallelujah s. I looked over at Muthoni, who had her eyes closed, nodding her head in agreement. Suddenly, I was transported back to my childhood in rural Massachusetts, where the prayers were endless and escape seemed impossible because I was a child. Children were viewed as extensions of their parents. If your parents said you were going to pray for five hours, that’s what you did. If they said you had to live your life a certain way, you did. Adults may have had the right to exercise free will, but a child certainly didn’t. And what did a child know about right and wrong, anyway? All I felt I could do, then and now, was lower my eyes and mumble along.

The minister sang through tears and a cracked voice, and she wasn’t the only one. By this time, many were crying. Then the pastor raised her arms, and everyone stopped singing. “Thank you for sharing your gift with us,” she said. “Now let us pray.”

The room combusted into prayers, ones that grumbled and ones that screeched. One woman fell to her knees and began speaking in tongues. Muthoni went to some corner to commune with God, and I was left alone in this sea of prayers and tears. I tried to appear as if I were in the spirit, practicing what my parents taught me. Oh God, thank you for my good health. Oh God, please protect my family. Oh God, help me find a stable job. This was what had gotten my parents through so many hard days. If I wanted to understand them and be close to them, didn’t I have to worship their God?

And yet, hadn’t I flown to another country to free myself—to piece myself into a woman who did not have to suffer in quiet desperation? I found myself looking for that small voice I’d once heard a pastor in Oakland speak of, the voice I was told represents the God of your own understanding. How do I leave? I asked as another woman began dancing in the circle. You can’t, the voice told me. But you can listen to me so I can tell you what to do next time.

The meeting continued for four hours. Four hours of singing and prayer. Four hours of chai, white bread, and a tray of mangoes, and somewhere in the mix, the pastor gave a sermon about finding your path when no one else understands it. At the end, she turned to me and asked, “Are you saved?”

Hadn’t I flown to another country to free myself—to piece myself into a woman who did not have to suffer in quiet desperation? Everyone looked at me eagerly, leaning forward, waiting for an answer. I looked at Muthoni, who was taking extra care to spread jam across a piece of bread. My mother had dragged me to my baptism when I was twelve or thirteen. There was something about plunging backward into the water that I didn’t like, but I was told it would be over soon. I could have given these women a long explanation of how I had traded in evangelical Christianity for yoga and vegan ice cream, but instead chose the answer that would make the pastor smile and set the room at ease.

“Yes,” I said, and took a gulp of chai.

I never made it to the birthday party.

*

“Twenty years old is a hard time for a Kenyan,” Otieno, my gracious local host, said through laughter when I told him about the fellowship meeting. “When I was Muthoni’s age, I was young and broke. My family had nothing to pass on to me, but I had God. It was something to believe in.”

Muthoni was young and open. A whole world in front of her, with a yearning to find her path. I understood the road she and others were walking, but mine went in a different direction. Three weeks passed, and she was still sending me WhatsApp messages asking if I’d like to go to another meeting with her.

Will you attend? The group wants to see you.

I kept giving her excuses: I have to work, I have my period, I’m going to Mombasa . But I heard that small voice, the voice of my own understanding, loud and clear. It said no .

I asked a good friend from Georgia, a queer black woman who had also left Christianity, how she responded to folks asking her to come to church. “‘No,’” she told me, “is a complete sentence.”

It took me a week to respond to Muthoni truthfully, but I knew I needed to stop making excuses and say no. No to the shame I had accumulated for seeing things differently from my parents, no to feeling alienated from my heritage because I couldn’t get down with G-O-D, and no to prayers that may have brought solace and insight to my parents and the Women of Faith while leaving me cold. I prefer to rendezvous with the divine by listening to my neighbors talk in the salon, or driving a bargain for avocados on a busy street. Perhaps that means I am unsaved, or a hippie, or even a witch—but at least it is who I choose to be.

Perhaps an African sings the songs that make them come alive and prays only if they want to. Perhaps an African knows they carry multiple intelligences that can’t always be graded or defined in linear terms. Perhaps an African woman takes care of the house and works if she so chooses, and uses her life to work for freedom. I’d like to think that some of my ancestors embodied these principles, and that I can, too.