People Arts & Culture Fifteen Minutes

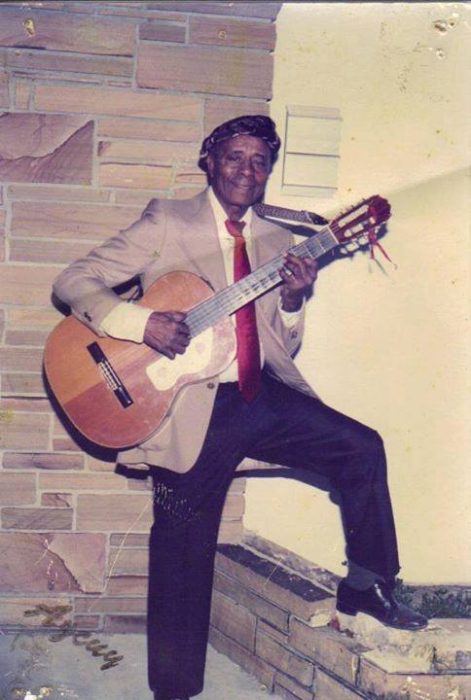

The Radio Repairman Who Started a Movement in Cuban Music

He begged his mother to let him buy the guitar. When she refused, reminding him that it was half of the month’s rent, he wept.

On a fateful afternoon in 1939, Alberto Menendez was walking home from his day job as a radio repairman in the eastern Havana neighborhood of Jesus Maria. He was only twelve years old, but he was already financially supporting his family—his father, who was from Cuba’s central farmlands in Camagüey, was accustomed to living in bateyes, settlement housing for laborers at the Cunagua sugar mill, and was not used to paying rent in the big city; his mother was a domestic worker reeling from the pain of an opened varicose vein, an untreated condition she had resigned herself to living with. Driven out of their rural home in Camagüey after the 1933 Brownsville hurricane, they spent years frequently relocating around the slums of Havana, until Menendez found a trade with steady promise.

He stood outside a neighborhood repairman’s shop and peered through his window, until he was taken in as an apprentice making radios at the start of World War II. At first, he made five cents a week, but worked his way up to five pesos a week, more than enough to cover his family’s rent.

Though Menendez was the second oldest of four, he was always the most practical of his siblings, and little could shake his sensibility.

But, on this afternoon a man was walking down the dusty streets with a guitar in hand. Menendez was intrigued. The man’s lungs were infected, and he was selling the guitar for two pesos to pay for treatment. Menendez had no real reason to want the guitar, but he could sing well enough to have gotten through to the second round at “La Corte Suprema del Arte”, the singing competition radio show that birthed Cuban superstars like Celia Cruz and Elena Burke. Music was a part of his life, at least peripherally. Just two houses down from his lived Pedro Izquierdo, known as Pello el Afrokan, the musician who invented “Mozambique,” an afro-Cuban style of music fusing bongos, cowbells, and trumpets. Izquierdo’s relatives were mostly Santeria priests , and on the last three nights of every month, they would play rumba without stopping. Devotees would come and go, performing in front of his indigent home. Menendez would watch from afar, entertained by the bombastic rhythms, but for him, music was a trivial pastime. It wasn’t until he saw the man with the guitar that he considered allowing himself the reprieve from responsibility.

He begged his mother to let him buy the guitar. When she refused, reminding him that it was half of the month’s rent, he wept. Izquierdo’s family eventually intervened and vouched for Menendez, reminding his mom of her son’s virtue. She acquiesced, and gave him her blessing to buy the guitar. He wiped his tears, flagged down the man and traded his hard-earned two pesos for the guitar. Menendez spent the rest of the day and the days to come sitting at his run-down home’s front doorway, teaching himself how to play.

Menendez has spent six decades refining his craft, performing with legendary Cuban artists during the Golden Age of Cuban music, witnessing history firsthand. But, his biggest accomplishment according to him is simply providing for his family and finding a space for art in his life.

“I’ve been playing guitar for seventy years,” recalls Menendez from his Little Havana apartment in Miami. “I never lived off of music, music was always just a complement for me.”

Today, Menendez is ninety-one, and spends his days playing dominoes and socializing at an adult daycare center in Miami Springs. His evenings are spent at his apartment where at least seven guitars are strewn across the living room floor. The walls are lined with framed flyers from past performances, artisanal woodwork, and photos of loved ones. By 1945, Menendez had opened his own radio repair shop where he was repairing upwards of twenty-five radios a day during the height of World War II. American jazz music had infiltrated Cuba and Menendez would listen to the station that played Nat King Cole and Cab Calloway during his long hours. When he wasn’t working, he was playing music with his friends Jose Antonio Mendez, and Leonel Bravet who could sing in English, and whose voice boasted a haunting resemblance to Nat King Cole. The three men, plus fourteen-year-old Omara Portuondo, who could imitate Lena Horne, formed a quartet called “Loquimbambia”, and the “filin” movement was born.

“Filin” is derived from the English word “feeling”. Founding member, Mendez is quoted as having said, “The word may go out of style, but the feeling won’t. Everything that is done with passion, with Cubania , with sentiment, has filin .”

“Filin turns out to be a global movement,” says Menendez, laughing incredulously. “You know why I was never a real musician? I thought these people were all descarados (shameless), they found a way to live without working, making music.”

Menendez may not be remembered as one of the Cuban greats, and he is quick to say he never lived off his music, but he did enable his son, Albert Sterling, to do that which he was never descarado (shameless) enough to do: become a musician.

In five years, Loquimbambia had a weekly filin show on the radio station CMQ and gained traction on the island. At the station, the artists formed a community. Menendez recalls playing guitar with the singer Benny More. He would cross the street to the neighborhood bar, Alaska, and buy a bottle of Pati Crusada rum that cost only twenty-five cents at the time. “One time, I smelled it and I got drunk from just the scent,” recalls Menendez. He mixed a drink for More and they’d sit in the studio together, playing boleros for hours.

By 1958, Loquimbambia had dissolved into a backup band for Bravet. On the eve of the revolution and the New Year, Menendez was playing at a party for higher-ups in Batista’s corrupt government. It seemed like a normal party, but by 1 a.m., it devolved into an orgy.

“We finished playing and then we left,” says Menendez. “When I got home, they told me, hey you know Batista left the country, and I thought, wow if they started shooting at those officials, we would have been killed too.”

In the years following the revolution, the politically ambivalent musicians fled the country while the Castro loyalists worked their way up in the few venues the state left intact. The golden age of Cuban music was decidedly over.

“I went along with Fidel like everyone else,” says Menendez. “Every person has an inner angel and demon, Fidel’s inner demon had woken up.”

Once Castro took over, Menendez pivoted again to work at the state-sponsored cinema, ICAIC, as a cameraman where he was continuously discriminated against by his white colleagues.

“They put a white man next to me and he took my position,” he says. As the revolution’s fervent idealism wore out, Menendez toiled on. He married his longtime love, Celia, who gave birth to his only son, Sterling. Menendez wasted no time teaching his son the basics of music, laying the groundwork for a trade that could inspire years of creative work and joy. When Sterling was just three years old, he remembers sitting on his father’s lap, listening to him play boleros on the guitar.

“[My father] was my first teacher,” says Sterling.

Menendez’s commitment to practicality paid off. His son entered a music conservatory in Guanabacoa at six years old. But the living conditions in post-revolutionary Cuba were difficult. Food became scarce, government-sanctioned electricity outages ( apagones) were commonplace, and political persecution was the norm. In 1980, Castro’s hasty decision to open the port of Mariel sparked a mass exodus known as the Mariel Boatlift—thousands of refugees boarded boats en route to Miami via the Straits of Florida for a twenty-four hour ride. Sterling, who was thirteen years old at the time, and his mother were among the many passengers. Menendez decided to stay in Cuba, fearing potential consequences.

“Mariel was a nightmare,” says Sterling. “There were sharks around the boat and I spent the entire time throwing up so much that only green bile would come out.”

They spent a few months at a refugee camp in Miami upon arrival, and then his mother became a domestic worker. When Sterling was not in school, he would help his mother clean. They eventually moved in with a wealthy family who had a grand piano in the living room. Sterling at first used the time away as a break, having endured seven years of rigorous practice. After settling into American life, his interest returned and he played piano for the wealthy homeowners.

“I was playing at the school thanks to my dad, but I was hating it,” says Sterling. “Not having an instrument made me fall in love with the music again.”

By 1984, Menendez reunited with his family in Miami, by way of Panama, where he earned his plane ticket fixing radios in Betania.

After retiring as an electrician in his late 60s, he decided to indulge himself and focused on his music fulltime. He spent the next fourteen years playing guitar in the back of a restaurant on Calle Ocho in Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood, and formed a band called Algo Nuevo, playing the music he saw the inception of in Cuba. His son meanwhile earned a full ride to the University of Miami’s School of Music. During the brief time that father and son were in Miami at the same time, Menendez opened for his son’s band with local musician Nil Lara.

“It was awesome, I was part of Nil’s band and my dad was a regular at the old gigs, he taught Nil how to play the Cuban tres guitar, that was really my dad [who taught Nil],” says Sterling. Upon graduation, Sterling met Shakira through mutual colleagues, and the two instantly clicked. He’s been playing piano with her for over twenty years.

“I never had to choose, because that’s what I always did, it was what I was meant to do,” says Sterling.

On Menendez’ 89 th birthday, I was invited to the party. He spent the day with his family at their home in the middle of Westchester, Miami. It was my first time meeting everyone there, but I instantly felt at ease. Four generations of friends and family convened to celebrate the life of a man who has endured so much, yet never lost that sense of filin . When it’s time to cut the cake, Sterling hops on the piano and performs a melody, later Menendez picks up a guitar and pluck a few chords, meanwhile, another member bangs on the bongos, forming an impromptu jam session that will last until the sun sets.