People Generations

Reconnecting With My Grandad’s Heritage As He Began to Forget It

My connections to the country and its people, my family, didn’t require control or even words. Touch, color, and togetherness were enough.

My grandad once pulled my mother aside for a stern word. He’d noticed my secretive yet obvious attempts to avoid eating the curries he’d lovingly prepared for us. I’d mash it with the rice, push it around the plate, and invest all my attention into the garlicky delight of naan. Spice was the enemy, I’d decided. Why couldn’t I just have fish fingers?

This reluctance grew with time as I learned that being brown made me different from everyone else at school. I’d fantasize about getting married so that I could change my surname from one that doesn’t fit in designated boxes on forms. I wasn’t ashamed of my Indian heritage, but I wasn’t particularly interested either.

I knew we had family that lived abroad that would visit us from time to time. I’d watch them marvel at the rolling Scottish hills while I guzzled the raspberries we were supposed to be picking. I knew that my dad generally went with an anglicised version of his first name—it’s just easier. And I knew that, in a past that seemed distant, his dad—my grandad—lived through something called Partition.

I didn’t know what Partition meant. I didn’t know that my young grandad and his family were forced to flee their home in East Bengal (now Pakistan) to Kolkata, because of rising violent tensions surrounding their Hindu faith. I had never even heard of the term “refugee,” nor how it might relate to my own family.

Grandad loved to talk, often dispensing with pleasantries in favor of diving into my career prospects before I’d even had the chance to say hello. He’d fascinate with tales of his family back home in India while conjuring curries in the kitchen, coating the surfaces with oils and spices, to my grandma’s dismay.

I’d nod along, letting the songs, food, and stories wash over me—enjoying their sensations but ignoring their effect. Our relationship existed in the present and future tense, not the past. It wasn’t until my twenties that I began to pay attention—when my connection to my heritage felt under threat. My grandad began to show signs of dementia, an illness that notoriously creates a fog that obscures and corrupts memory.

Sitting at the dinner table, his words looped back, over, and around themselves as they began to confound him. His voice would trail off, leaving disrupted thoughts and memories hanging in a cloud around him as he slowly sank into his armchair.

Grandad’s stories began to fade just as I began to gain interest, and I felt the bite of shame as I realized how little attention I’d paid. Suddenly, an invisible force was slowly untying my family’s connections to its past.

As I drove home from one of my weekend visits to see my family, the road ahead stretching into darkness, I found myself wrestling spiraling thoughts. My connection to India was built on fading foundations, and I was unable to connect meaningfully with a culture that was becoming increasingly important to me. Looking backwards wasn’t working.

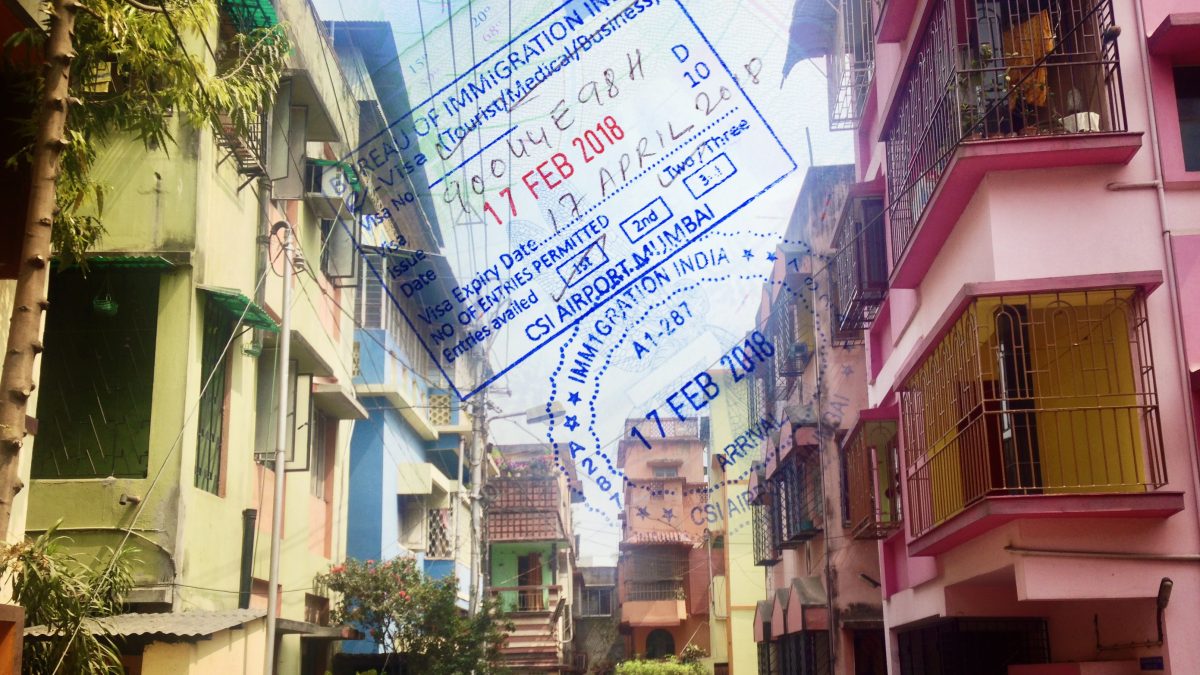

Somewhere on the motorway, it struck me that perhaps I was looking in the wrong place. Perhaps this bond was something ahead of me, something I should be forging myself. In an uncharacteristically spontaneous act, I resolved that the best way forward would be to travel to India. I would reconnect with my heritage by immersing myself in the culture I’d neglected. Even better, I’d travel by myself.

Arriving home near midnight, I dived headfirst into planning and by the morning had drawn up a month-long adventure across the globe.

Grandad’s stories began to fade just as I began to gain interest, and I felt the bite of shame as I realized how little attention I’d paid. *

After a whirlwind of organization, immunization, and travel, I was spat out into the fierce, dry heat of Mumbai. My internal temperature immediately rose at least twenty degrees and I felt my shirt stick to my back, where it stayed for the next few weeks.

On leaving the airport, I was struck by a wall of noise. The air was thick with engines and horns, the horizon reached by houses built into and atop one another, and my nose full of a heady mix of incense, dust, overripe fruit, and fumes. My senses were overwhelmed, my brain struggling to comprehend the complexity of what it was experiencing. I felt a surge of adrenaline, which masked my nerves with a sense of curious awe.

Aware that traveling alone to unfamiliar territory was unwise, I had persuaded my close friend Dominique to travel with me—immediately being rewarded for this decision when she successfully haggled a driver down to what we smugly thought was a reasonable fare to our Airbnb. Blissfully unaware we’d been totally ripped off, we packed ourselves and our belongings into the back of a cab before bounding up the stairs of our tower block with glee, picturing longed-for showers.

Opening the door to the apartment, we discovered the advertized three rooms were actually one, complete with smashed windows, a dead rat in the curtains, and a burnt-out kettle. Investigating the bathroom revealed something living in the toilet, and there was no electricity in the plugs.

My bravery left me all at once. Exhausted, I couldn’t hold off the anxiety that had been clawing at the edges of my brain since we’d arrived. I fell apart, perched on the edge of a bed I was too nervous to rest my full weight upon.

The city outside continued to stampede at an intimidating pace. People fired past the window in every direction, speaking in a multitude of languages, none of which I could understand. I felt foolish and stranded in a place where I clearly did not belong, a far cry from the emotional homecoming I’d longed for.

As is always best in these situations, I called my mum. Stealing Wi-Fi from the flat below, I sobbed down the phone. She lovingly and patiently pointed out that there was no way I could leave the country immediately (as was my wish) and that perhaps we should find a place to sleep, at least for one night.

One thing to know about Indian families is that there is always a cousin nearby. We managed to make contact with one such cousin, Mimi, who redirected us to a hotel that had solid walls, complete windows, and a lock on the door.

Mimi took us out to dinner that evening, to make sure we hadn’t retreated entirely. Her eyes twinkled at me over a mountain of food. “I never thought I’d see the day when you ate this much spice!”

We both knew she was referring to my ungrateful anti-curry phase, so I over-ate in an attempt to prove I had matured—promptly ending up in a carb coma, falling asleep at the table.

Even after a good sleep, I was still feeling shaken. I craved stability and the ability to impose some semblance of order over my surroundings. But India was pushing back. Control, one of the foundations upon which I rely to keep my anxiety in check, was being wrestled from my hands.

Mimi sensed that we might be in need of a bit of help. Over the next few days, she whisked us through the bustling streets of Mumbai, an incredible city of much traffic and many parts with wealthy suburbs housing India’s elite in skyscrapers overlooking Dharavi, one of the world’s largest slums.

Faded imperial grandeur was juxtaposed with markets selling an odd combination of spices, kettles, fabric, and flip-flops. We clung for dear life to tuk-tuks (glorified tricycles with a cab on the back powered by a lawnmower engine), which weaved through the torrential traffic. We took a boat to Elephanta Island, where to everyone’s glee I was chased by a wild cow that had taken a particular shine to me. We gorged ourselves silly on dabeli, dal vada, and bhutta. And I pretended to enjoy the myriad of Indian sweets that, to me, all taste of grainy paste (apart from my one true love, gulab jamun).

Throughout our busy days, my thoughts often turned to Grandad, who had always been a bastion of calm control in my eyes—never one to express anything other than quiet confidence. I wondered how on earth he had come from this chaos, and how he’d coped. I wished more than anything that I could ask him.

Standing on Mimi’s balcony one evening, staring out at the saffron glow of the city, I quietly shared with Dominique my fear that I might never be able to exert any semblance of control in this wonderfully unruly country, and that I didn’t know how I would manage the next three weeks. She said nothing, but shuffled in a little closer.

I wondered how on earth he had come from this chaos, and how he’d coped. I wished more than anything that I could ask him.

*

Before departing Mumbai, Dominique and I bought each other wedding rings—a safety marriage in its truest sense. White women in India often receive a large number of unwanted advances and wearing a ring helps to reduce the likelihood of such intrusion. I also wore a ring—and was careful discussing my love life, even with family. Homosexuality was decriminalised in India only in September of 2018, six months after our trip. Sadly, homophobia there is just as prevalent now as it was then; violent attacks on queer people in India are commonplace .

However, during our trip, there were men holding hands in public, hugging one another or with their arms draped over each other. At our next stop in Kochi, Kerala, two men watched the sun set while holding hands. I plucked up the courage to ask why. Their answer was simple: Because we are best friends .

Though it sounds strange that in a culture where same-sex love cannot be expressed, friendships are so openly affectionate. We live in a similar way in Britain, yet reversed. Showing queer love is, in the main, more acceptable here, but any tactile expression of friendship between two men raises more than an eyebrow.

I clearly wasn’t ready for marriage, because after losing my ring three times in two days, I then accidentally smashed it, effectively annulling Dominique’s and my fraudulent relationship. My brief venture back into the closet reminded me of how far I’ve come. I am so comfortable being openly gay now that it felt bizarre to hide it. Sadly, this is a part of myself that I likely won’t be able to share with my Indian family, an obstacle that it may prove hard to overcome.

Our time in Kochi was characterized by my growing acceptance that we’d be swept along by the ebbs and flows of the day. Time and tardiness appeared to be loose concepts. Things simply happened when they happened, and if you had to wait, then so be it. Rather than being a source of anxiety, this became oddly soothing as we whiled away days exploring the diverse mixture of religion, culture, and architecture in the town.

Relaxing my grip on the reins, we stumbled across many wonderful experiences: trips to the mangroves, kathakali performances, and the most delicious kati rolls I have ever tasted. Sitting on a bench overlooking the Arabian Sea, I suggested to Dominique that she might be rather impressed with how relaxed I was being.

She arched an eyebrow. “Planning to be spontaneous is still planning,” she said, pinching the remainder of my watermelon. Nevertheless, I counted it as a win, leaving Kochi feeling slightly more equipped to handle whatever the remainder of our trip would throw at us.

After a sojourn across various other parts of India, including visiting Qutb Minar (underrated), the Taj Mahal (stunning), and the Lotus Temple (closed on Mondays—guess which day we went), we found ourselves in Kolkata, where we stayed with my grandad’s brother and his family.

Here, we discovered that there would be no Wi-Fi for this final stage of our journey, tugging the last vestiges of control from my hands. I could no longer track where I was on Google Maps, instead having to trust drivers or to simply get lost. I asked strangers to translate signs and menus. I never really knew what time it was. Rather than causing distress, this began to feel somewhat cathartic. We were fully immersed in the world around us, forced to remain in the present.

Our visit coincided with Holi, the Hindu festival that heralds the arrival of spring, where families and friends gather and celebrate with the throwing and painting of colors—an occasion for people to reset and renew themselves, casting off past burdens.

We rubbed coconut oil into our skin to prevent the colors from staining and tagged along with my great-uncle’s family to visit friends and relatives. I’d seen images of Holi online (and bastardized versions in fresher’s parties), and had braced myself for riots of music and color—but was surprised by their conspicuous absence.

Apart from pockets of intense festivity, Kolkata was a ghost town, its characteristically crowded streets conspicuously barren. The horns, engines, and exhausts that typically filled the air were replaced with a dusty silence that felt eerie. Every so often, groups of giggling color-drenched children punctured the peace, firing water guns with glee at half-heartedly tutting parents. We shared a moment of connection with each group that passed us, but rather than throwing colors as I’d expected, it was a more mellow, meaningful affair.

The first family we met were strangers. Following my cousin’s lead, we introduced ourselves before using our hands to gently brush color across their foreheads, cheeks, and arms. We murmured wishes of peace and prosperity, feeling an uncanny connection pass between us. We couldn’t understand each other’s words yet knew instinctively what was being said. I’m not a person of faith, but this felt close to a religious experience.

A still, silent moment followed where I was overwhelmed by a sense of togetherness and belonging with this family, who no longer felt like strangers, before we parted ways.

Our tour of the neighborhood was hours long and included visiting relatives that I’d only seen a handful of times. To my surprise, they knew almost everything about me. They eagerly produced photos of me as a baby, shared embarrassing stories of my childhood, chuckled at photos of me in my kilt on prom night, and fondly remembered the trips to the Scottish countryside where we’d picked raspberries together. My grandad had shared everything with them. They were so proud of the life they’d seen me live.

I felt my cheeks redden with shame for having taken so long to reach back out to them, and stammered an awfully inadequate apology. But they waved it away. Their love was not conditional on reciprocation.

My great-uncle asked how his brother, my grandad, was. They’d also been anxiously following his illness. The room paused, a quiet wave of grief washing over us all. My cousin took my hand. We sat, still, in this sadness for a moment. This sadness, I realized, was another form of love. It felt right to share it with my family.

Their love was not conditional on reciprocation. Holi truly reset and renewed relationships, tying me back to my roots in an unexpected way. India had been there all along, willing and waiting for me to reach out. I finally felt somewhat grounded, finding that my connections to the country and its people, my family, didn’t require control or even words. Touch, color, and togetherness were enough.

Now, Grandad doesn’t speak much, if at all. It pains me to know there are things about his life that will become unknowable to me. But I now understand that I will always be able to find and foster my connection to him. Our relationship exists in the songs he sings, in the stories he told, and in the family he loves. I will sing the same songs, tell the same stories, and love the same family. And in that, our bond lives on.

Our visits are quieter now. Normally, we just sit together and watch the world go by.

Every so often, I’ll make him a curry. His eyes always light up.

“Finally.” He smiles.