People Health Mental Health

Covid-19, Memory, and Remembering My Grandma

Can I trust the sparse memories in my long-Covid brain? If I don’t record this, will my Frankenstein-ed memories escape, just like Grandma’s did?

When reminiscing or when prompted, people often say something along the lines of oh my god, I totally forgot! as a way to indicate something, ironically, that they had just instantly remembered. For me, that moment of recognition doesn’t always arrive anymore.

Ever since I got Covid in March 2020, the landscape of my brain became the first “new normal” I was forced to navigate. My sense of taste and smell, my mood disorders, and my memories have all been impacted by the virus. I spent about two and a half weeks waking up every day, frantically sniffing my scented hand soap and hoping that today’s breakfast sandwich would have flavor rather than just texture and the sensation of too much hot sauce (as an attempt to feel something).

At the time, I was one of many gay millennials in New York City with a celebrity crush on Alison Roman and a daily habit of watching Bon Appétit Test Kitchen YouTube videos. I couldn’t bear the thought of losing my sense of taste. My taste, thankfully, came back, but it returned distorted. Peanut butter tasted charred. Coffee required far too much brown sugar to be palatable. Mint toothpaste tasted chemical on my tongue. Maybe the most distressing change of all was that, every time I cooked or ordered any meat, it either tasted rotten, undercooked, or like bleach.

I tried cooking around the problems: I avoided peanuts and mint, and I mostly made pescatarian dishes. Every month or so, I’d test the waters with a chicken or lamb recipe, making sure to create flavorful condiments in an attempt to anticipate and drown out any unwanted flavors created by my post-Covid brain. I remember roasting a chicken for my partner, absolutely paranoid that I was inadvertently poisoning us. She said everything tasted and smelled good, but I couldn’t tell if she was just being nice. I could still taste bleach and had been in the kitchen so long I figured I’d just become desensitized to the smell of garlicky roasted chicken with vegetables and oregano. Aren’t all Greeks overly exposed to that scent, anyway?

One day, about six months after my Covid case, I cooked brunch, cleaned my kitchen, and went to lie down in my room. I don’t know how much time I passed in the dark, but when I opened my bedroom door, my apartment was filled with smoke. I couldn’t smell the smoke from my room. That’s one way to learn you need to change the batteries in your smoke detector.

After I addressed the situation, I saw that, before I went into my room, I had started lazily re-seasoning my cast-iron skillet by coating it in a thin layer of canola oil and allowing it to come up to a smoke point on the stovetop. I had no recollection of starting that process, so I had no reason to remember to turn off the burner.

This wasn’t normal forgetting.

I panicked. I cried. I thought of my grandmother.

*

From what I remember, Grandma always seemed a little forgetful. But I had always chalked that up to her age and the fact that she was hard-of-hearing. I didn’t think anything was out of the ordinary. It’s normal to have to repeat things to older relatives, right? After all, I spent my childhood and adolescence moving all over the country, only seeing my extended family once or twice a year, so of course she wouldn’t remember details like the fact that I’ve never gone by the name “Madison.” Most of my relatives routinely forgot this detail, too, so it didn’t seem notable at the time. Whenever we walked into my grandparents’ house, we’d instantly smell her cooking filled with warm butter and oregano, then we’d inevitably start flipping through George Carlin books on the coffee table. We’d hug and kiss on the cheek, but also routinely refer to people we knew as “rat bastards” (said in a New York accent—my first real curse word!).

As my grandparents aged, Grandma’s mobility didn’t deteriorate as much as my grandfather’s, so it seemed egalitarian that his mind seemed sharper than hers. He would sometimes get impatient with her if she wasn’t moving quickly enough to stir the eggs into the avgolemono to stop them from curdling. I never knew if she forgot how quickly she had to move during that part of the recipe, or if she was just getting older. After dinner, though, my grandfather would sing dirty songs to Grandma in Greek while accompanying himself on the mandolin. She would smile slyly and laugh, telling him to stop being inappropriate. She remembered the music and lyrics—and two languages!—but it must have just slipped her mind that none of us, her grandchildren, could speak even the basic Greek required to understand those songs.

According to family legend, my grandfather always said he hoped he would die the day before Grandma did, so he wouldn’t have to live a day without her. And, in a way, he got his wish. His body did stop before hers did. Grandma was in the house in the days when my grandfather was taken to and from the hospital after years of pain, avoiding doctors, and then discovering that cancer had spread all over his body.

Hours after my grandfather died, she looked around, confused. She asked where my grandfather had gone. Still, she insisted, he should be returning home soon.

She had been there as family members filed in to say goodbye to him. She was there as his body was taken away on a stretcher. She was there when we drank gin and tonics with lemon as we cried, laughed, and grieved together. Still, she did not remember that her husband had died that morning.

This wasn’t normal forgetting.

In the five years between my grandparents’ deaths, Grandma was moved into care facilities specific to people with dementia. My mom and uncles lived nearby and often visited. I heard stories about Grandma waking up in the middle of the night, getting dressed, not knowing where she was, feeling distressed, and then forgetting that the entire episode had ever happened. I visited one of the facilities one time and was asked to sing for the residents. They knew every single word and note to the Rodgers and Hammerstein and Great American Songbook songs, even if they didn’t know where they were or who they were with.

This wasn’t normal forgetting. I remember one of my last conversations with Grandma: We were looking at some sort of kitchen supply catalog. She had no clue who I was at that point, but we could point to pictures and say short pleasant things about roasting chicken legs and potatoes, or layering pasta, sauce, and bechamel for pastichio. It occurred to me that, at some point in my teenage years, I’d had my final dinner cooked by Grandma and didn’t know that it was happening.

As I write this, just after the one-year anniversary of my grandmother’s death, I’m questioning my own account. One day in 2020, I said with my full chest that there are ten months in a year; is this the brain of someone who should be entrusted to remember anything or anyone? Most of my first pass at writing this essay has been a litany of questions without answers: How many of these memories were lived experiences, and how many of them are creations patchworked from remnants of sense memory, clumsily pinned together by my adult understanding? Can I even trust the sparse memories in my long-Covid brain? If I don’t record this, will these Frankenstein-ed memories of mine escape, just like Grandma’s did?

*

It turns out that both Alzheimer’s disease and Covid-19 can impact the olfactory bulb, a part of the brain that sends signals about smell from the nose to other parts of the brain. The olfactory bulb also has connections to the temporal lobe , which is the region of the brain impacted by dementia, since that is where the hippocampus is located. The hippocampus is noteworthy in the context of dementia, because it is the center of the brain responsible for memory and learning. Anosmia, the loss of taste and smell, is a common symptom of Covid, but it is also an early symptom that can predict the onset of Alzheimer’s disease .

As my grandmother got older, she would write down her famous chocolate-chip cookie recipe for her children, nieces, and nephews. Over the years, the salt measurements in that one recipe would change, each handwritten card inconsistent with another. We used to joke that it was deliberate, so none of us could ever replicate or usurp her cookie glory. Now I wonder if her sense of smell and taste were changing on a neurological level, for the same reason that her memories faded.

Connected to the olfactory bulb is the temporal lobe . The temporal lobe and the parietal lobes are responsible for working memory , which is the pieces of information we only hold onto for short amounts of time, like remembering how many cups of chicken stock are in the recipe in the moments between reading the cookbook and getting out the measuring cups. This type of memory can be impacted in early stages of some types of dementia. This type of memory also can be impaired by brain fog as seen in patients with chronic fatigue and long Covid.

Maybe that’s why Grandma couldn’t remember where her husband had gone on the night of his death; she may have already forgotten he had been taken out of the apartment within minutes of it happening. Maybe that’s why I still couldn’t remember that I turned on the stove even after I knew that I’d filled my apartment with smoke.

If I don’t record this, will these Frankenstein-ed memories of mine escape, just like Grandma’s did? The hippocampus provides temporary storage for episodic memory , which is the autobiographical and emotional recall of events, like when you’re trapped in small talk and being asked how your weekend was. Eventually, certain long-term memories are relocated to the cerebral cortex and do not involve the hippocampus as heavily; this is why you might remember this most recent weekend and a particularly significant past birthday weekend, but you don’t remember every single weekend you’ve ever experienced.

Maybe that’s why, in the last years of her life, Grandma couldn’t remember what she’d had for breakfast but she could remember dates she went on with my grandfather in the 1950s. The part of her brain that would have been holding that morning’s quotidien toast and jam was compromised, but the part of her brain required for recalling a night with the love of her life about sixty years prior remained intact. Maybe that’s why I can’t reliably comprehend a text message I’ve read only once, but I can remember Grandma.

Semantic memory accounts for general knowledge, language skills, and other types of information that are not tied to personal events. If you’ve ever participated in a spelling bee or played a game of Trivial Pursuit, you have called upon semantic memory, which is typically associated with the temporal lobe and hippocampus. Patients with semantic dementia and early stages of Alzheimer’s can experience difficulty with finding the right word, which is often a result of damage to the left temporal lobe.

During and after my Covid case in 2020, I began losing words, furiously tapping my thumb and forefinger together, trying to remember the word for the thing on the table in front of me, knowing that the words folding typewriter weren’t right. It took me longer than I’d care to admit to conjure the word laptop . But I had a newfound understanding of Grandma. The day after my grandfather died, Grandma couldn’t find the word lesbian when she asked me if the blonde lady in a suit on the television (Ellen Degeneres) was “one of them” (yes). No homophobia, just forgetting.

When I began researching to write this essay, half the Google results already had purple links and “Last Visited” dates that I couldn’t recall. In a case of cruel irony, I read months ago (and subsequently forgot) that brain scans showing differences between brains before and after mild to moderate Covid cases have been examined in a large-scale preliminary study out of the UK . These findings indicate that the brains of patients who had tested positive for Covid experienced an increase in tissue damage in the olfactory cortex and/or a reduction in gray matter thickness in the temporal lobe, among other significant effects on the brain associated with Covid. The findings in the UK study have not yet been peer-reviewed as of this writing, but this type of research sets a precedent in the long, winding road to understanding the long-term impact of this pandemic.

Because the areas of the brain impacted by loss of taste and smell in Covid cases are also those impacted by dementia, any possible connection between Covid-19 infection and onset of dementia is currently being researched as well.

*

Ever since my taste came back, I’ve been trying to preserve my limited memories by attempting to cook my grandmother’s recipes. I don’t have any of her handwritten copies because I was not astute enough to realize that I had a limited window of time to ask for them before her memories had begun to fade. I have to recreate them from vignettes of hazy afternoons spent almost half my lifetime ago, and I don’t trust my own memory or my taste buds.

Ever since my taste came back, I’ve been trying to preserve my limited memories by attempting to cook my grandmother’s recipes. Once meat stopped tasting like bleach, all I wanted was the braised lamb and orzo that I associate with visits to my grandparents’ apartment. I never got to watch her make it. I never got to ask her about the proportions of tomato to orzo to water. Did she use canned tomatoes or fresh ones? Was the warmth just from cinnamon, or did she add cloves, too? What cut of lamb did she buy?

I can’t fully remember what it tasted like anymore, but I know I loved it.

Even if I get it right, will I ever truly know if I did? Sometimes I’m just so grateful that my attempts don’t taste like bleach that I can’t quite make out if what I’ve made actually tastes close to how Grandma would make it. I ask myself if she’d approve of using my second hand Le Creuset dutch oven to make this a one-pot affair rather than dirtying a pasta pot, a saucepan, and a Pyrex—wasn’t that how she did it?

I don’t have anyone in my day-to-day life who ever got to meet Grandma, so I cook for them—my partner, my roommate, and the occasional indoors-approved friend—knowing they’ll never truly understand the context for what I’m chasing. I think I’m getting close. I could say the same of most of my memories in general.

The final time I visited Grandma, my mom greeted her:

“Do you know who I am?”

A sly smile. “Of course. You’re my sister.”

“I’m your daughter.”

A delighted gasp. “That’s even better.”

I hope, despite my flaws and fumbling, I will land on something that feels like family.

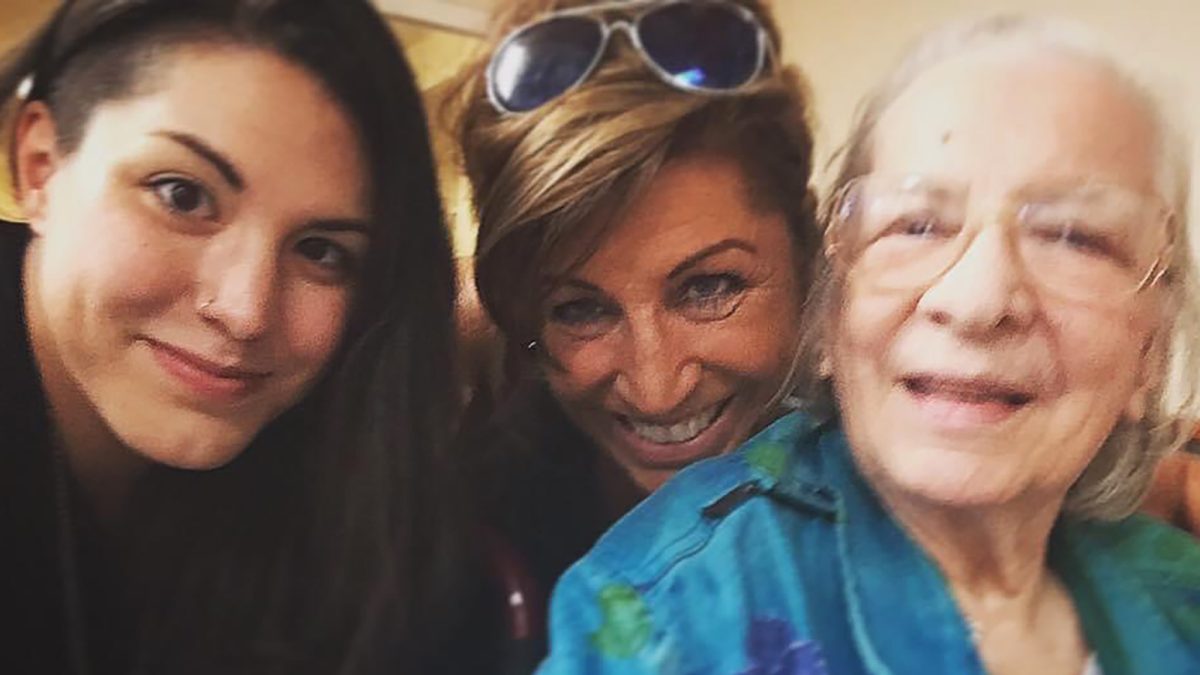

Photograph courtesy of the author