People Family Legacies

My Family’s Relationship with the Unseen

Maybe my dreams were trying to tell me something. Maybe I had what I liked to call, jokingly, “the ElGenaidi Gift.”

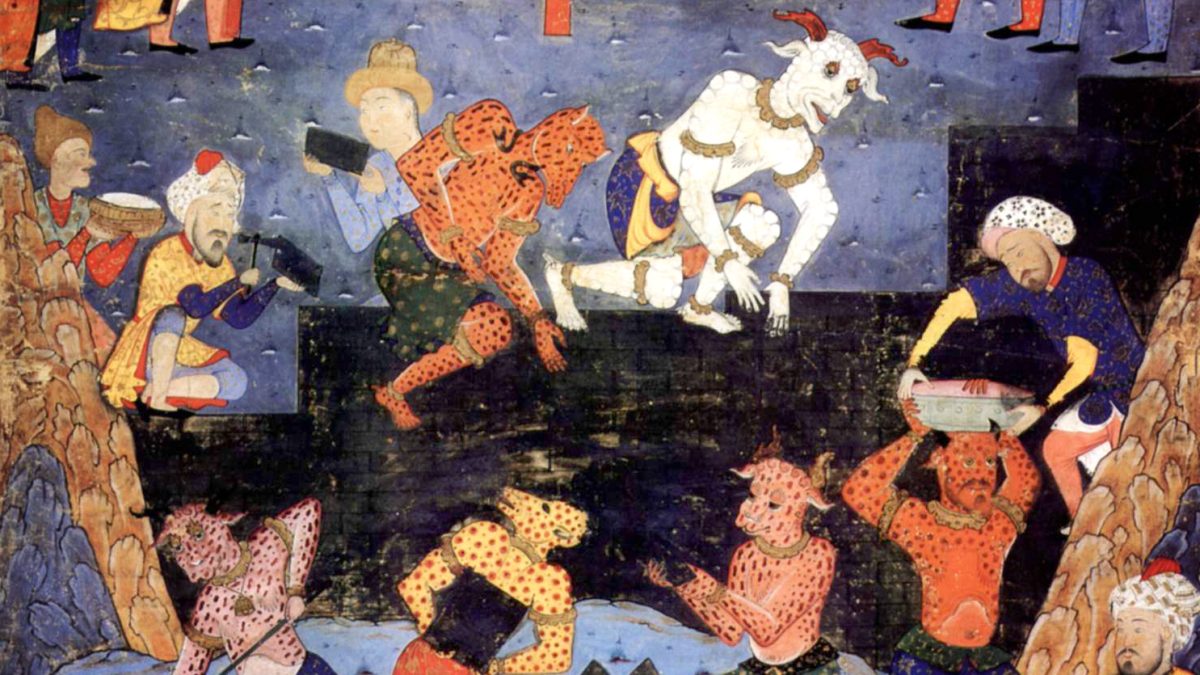

Every religion, every culture, has its own folklore, its own mythology, its own take on the supernatural. In Islam, we believe in djinn. A quick Google search for djinn surfaces a series of stereotypical images, all akin to the genie in Aladdin —blue with a goatee and ponytail.

But djinn are just like us. They live among us—invisible entities who existed on Earth before Adam, created by God out of fire. They resemble humans: They have children, lives. At the end of the world, they will be judged like humans too, condemned to either heaven or hell. At least, that’s what I was taught growing up.

In October 2000, the 1973 film The Exorcist was re-released in theaters. My family was all geared up to see the film. I insisted on going to the movies with my dad, aunt, uncle, and cousins that day, even though my dad told me to stay home with the younger kids.

“Kareem is going,” I said, eleven years old and pleading to tag along, “and we’re the same age.”

My dad gave in, and we all piled into the car to head to the theater.

Scenes from the film remain vivid in my mind. Regan tells her mom that her bed is shaking, and her mom doesn’t believe her. Later, Regan’s bed violently jerks up and down, with her and her mom in it. Even later, Regan, possessed, screams and shouts expletives as her body contorts in odd positions atop her bed. A few scenes later, Regan races down the stairs backwards on all fours, blood spurting out of her mouth.

At that moment, unable to take even another minute of abject horror, I turned to my dad and said, “I want to leave.”

My dad and I exited the theater and waited for the rest of our family in the empty lobby. It was quiet; all the concession employees had already gone home. When my dad left to use the restroom, I sat there alone, my chest growing heavier, my heart beating faster. The hair on my arms prickled up. I was afraid some supernatural presence was there with me.

Under my breath, I recited a prayer—a verse that my parents had me memorize from the Quran.

Bismillah al rahman al rahim

Kulhu allahu ahad . . .

In the name of God most gracious, most merciful

He is Allah, the one and only . . .

At the time, I didn’t even know what the Arabic words I was saying meant, the dialect different from the one my family spoke, but I hoped more than anything that the prayer would protect me.

After we got home from the movies that night, I was too afraid to go to sleep. My dad had to come and sleep next to me. I pictured the bed shaking, a demon entering my body, blood pouring out of my mouth. I kept feeling an eerie presence in the room, and again, I murmured every verse I knew from the Quran.

“ Bismillah al rahman al rahim . . . ” I began to whisper at an inaudible volume alongside my dad’s snores, right up until I fell asleep.

My dad took me back to my mom’s house at the end of the weekend. Again, I was too scared to sleep, afraid that something would possess me—that a demon lurked in my home. For three months after that, I slept with the lights on, took quick showers so as not to be alone for too long, avoided looking in mirrors in case I saw something behind me.

In those moments when my heart would start racing and the hair on my arms would get prickly from the goosebumps, I began praying again—usually repeating the same three Quranic verses until I felt safe. It was unlikely that there was anything actually there, and that, instead, my own childhood imagination and fears were getting the best of me. But seeing those first thirty to forty minutes of The Exorcist marked the beginning of my journey with faith and djinn.

*

I was raised Muslim. As a kid, my mom would have me recite verses from the Quran, and eventually, my parents hired an Arabic and Islam tutor to teach me reading, writing, and religion. Though my parents weren’t militant about it, they’d occasionally have me pray with them, bending down, standing up, reciting those verses that are locked into my memory—the verses that I repeated in times of fear. They taught me to fast during Ramadan, and all the basic rules: no drinking, no drugs, no pork, no sex before marriage.

As a whole, though, I remained somewhat uninterested in religion. I considered it a burden on day to day life. I was more interested in the immediate present—friends, books, TV—to be worried about the afterlife. I also lived in a secular society, where too much faith would be scoffed at. Plus, there were too many rules, too many reasons to feel guilty. Would God really punish me if I didn’t fast during Ramadan?

The tales of djinn, though—of the supernatural—always captured my attention. My dad once told me the story of Ghanima—his grandmother on his father’s side, my great grandmother—who lived in Egypt. My dad’s aunt once walked into a room to find Ghanima and saw, according to my dad, “a man dressed in a very formal suit, with a top hat and mustache.” The man was leaning on the fireplace mantle and disappeared just seconds later. Across from where the man had just stood, Ghanima sat in a chair, like nothing at all odd had just happened.

The aunt, confused, asked about what she saw and told Ghanima of the man in the suit.

“Don’t worry about him,” Ghanima said. “We’ve broken bread together”—an expression in Arabic meaning there was a longstanding history between them. She never explained the story further.

“Don’t worry about him,” Ghanima said. “We’ve broken bread together.” Allegedly, Ghanima could speak to djinn. The first time my dad told me this story, I listened intently, thinking back on my childhood, back to the movie theater, where I whispered Quranic verses as a means of protection from what I couldn’t see. According to Islam, some djinn can make themselves visible to humans—particularly humans with special abilities, who have some kind of spiritual connection to the unseen.

“She was clairvoyant, I guess,” my dad said of Ghanima. “It’s not really knowing the future. It’s just knowing—knowing something more.”

The ability to see the unseen is allegedly common in our family. Ghanima’s father apparently had it; all her siblings too. A few years back, my dad’s sister woke up in the middle of the night with a bad feeling. She called her son—my cousin—to check up on him. At that very moment, he was in the hospital with low blood sugar. It’s like something woke her up, or a part of her knew.

My dad later told me of his own cousin’s relationship with a djinn in Egypt. Years ago, his cousin claimed to be seeing a woman who would appear to him at night, and they would sleep together. He claimed that she was a djinn woman and that she considered him her husband. The djinn soon overtook his life. He was distracted during prayer and often felt physically drained. He lost an unhealthy amount of weight, and the djinn woman followed him everywhere. Eventually, his mother took him to a medium who exorcised the djinn, and soon after, his life began to improve. He gained back the weight and returned to his normal self.

“Possession is real,” my dad said, “and exorcism is okay.”

I laughed. At the same time, he was confirming all of my worst fears.

I wanted to rationalize all of this with science or logic, though. And, of course, attributing what could have been mental health issues to the supernatural was no doubt harmful. I asked my dad, a doctor, “Do you ever consider that it might be mental illness?”

He replied, “I would, if not for the fact that he’s totally better now.”

This cousin is apparently now married to a human woman, with human children. He doesn’t see djinn anymore.

I did some rudimentary research on my own, reading blogs and following various scholars on Twitter. In Islamic folklore, it’s said that most djinn who make themselves visible to humans have malevolent intentions, not unlike a demon. Sometimes, they’re even able to possess you.

Still, I took those family stories with a grain of salt. In many ways, they were so distant from my reality that it was easy to dismiss them as intergenerational myths and legends. No one could really confirm the story of Ghanima, who passed away before I was even born.

But then, about five years back, my cousin came to me with her own djinn story. She was on a trip to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, a place where djinn were known to reside. One night in the mountains, she woke up and saw a figure that looked like a woman standing at the foot of her bed. The woman had long, black hair falling past her shoulders, and she wore a white dress.

“Possession is real,” my dad said, “and exorcism is okay.” My cousin remained still, afraid for a moment that someone had broken in. The figure, too, stayed in place. Eventually, my cousin moved, and the figure approached the bed. My cousin, too terrified now to get up, shut her eyes and recited the shahada, the declaration of faith in Islam, in which Muslims declare that there is no God but God, and Muhammed is the Messenger of God. Seconds later, when she opened her eyes, she saw that the figure had disappeared.

When she returned from her trip, I asked if she was sure she hadn’t dreamt it.

“I was awake,” she said, with absolute certainty.

I didn’t know what to believe, given my close friendship with that cousin. I knew her, and I knew, like me, she was rational. Suddenly, stories of djinn had pervaded our generation, and it no longer seemed a far-off fairy tale.

These stories often make me wonder if maybe we are special. Maybe there’s something in our family connecting us to a world we can only begin to imagine. Or maybe I just want to feel that way. If I’m connected to something larger than myself, then perhaps there’s some greater meaning or purpose to my life— to life —something I haven’t yet discovered.

I don’t know if I believe the stories, but I always ask to hear more. I’m drawn to this family history and our ties to the supernatural—to what we can’t see.

Still, I can’t bring myself to fully commit to religion. I remember one day in college, when I was staying with my dad, I had plans to go paintballing with all the other members of the school newspaper. It was Ramadan. My family was all fasting.

“I don’t think I can fast tomorrow,” I told my dad the night before my paintball excursion—just so he wouldn’t ask me questions when he saw me eating breakfast the next morning.

“Why not?” he said.

“I’m going paintballing. It’ll be too difficult.”

My dad sighed. “That’s not really an excuse,” he said. “But it’s your decision.”

His tone carried the guilt I was meant to feel. But I didn’t feel guilty for not fasting that day. Instead, I felt guilty for disappointing my father. Moments like that, in which rules came in to make my life more difficult, only pushed me further away from religion. I didn’t want to fast, just as I didn’t always want to pray when my parents asked it of me, or when I don’t want to abstain from all the behaviors Islam considers haram, forbidden.

Still, though, in times of fear or the unknown, I remember my roots and my faith and am called back to that night in the movie theater. In those moments, I do believe something else is out there, though I don’t always know what to make of it.

While I remain a skeptic, my upbringing and my family’s history keeps me believing that something exists beyond the world that we know and see. For years after I went to see The Exorcist , I fell asleep each night reciting the same three Quranic verses. At first, it was out of fear, a need for protection from demons, djinn, or whatever else might be in the room with me.

Whether anything was there or not, just saying the verses, sometimes over and over, comforted me and made me feel safe. After the fear subsided, and months passed, I began reciting the verses out of habit, each and every night before bed. The habit eventually faded, but it took many years, and now, every once in a while, I remember.

Several months back, I had a recurring nightmare about my stepfather for three nights in a row. Then I spoke to my mom; the nightmares coincided with some family issues that were occurring on those exact days. Maybe my dreams were trying to tell me something. Maybe I had what I liked to call, jokingly, “the ElGenaidi Gift.”

I don’t know if it was a coincidence or not. But when I told my dad, he said, without even a hint of irony, “That comes from your grandmother. It will grow with time.”

For years, I’ve been asking myself what I believe. I still don’t have the answers, but I want to believe in something, even if it’s just my family’s stories.