People Health Body Language

How Do We Survive Suicide?

How much does my fear of owning this darker voice hinge on a cultural insistence that it’s unhealthy, even unnatural? What if I’m all of it?

My brother wants to die and I can’t make him better.

I wrote this in May of 2018, on a blank page in the middle of a notebook full of research on suicide. This was a year after I’d been discharged from the Maimonides psych ward in Brooklyn for a massive depressive episode. I’d been ruminating on the tendency toward suicide since leaving the hospital, reading the writing of people who’d killed themselves, chasing this idea that doing so might demystify the moment in which a person goes from wanting to do it to doing it.

Nominally, it was a project about preventing my future suicide—something I’d often suspected was inevitable but, now, in a new recovery and hoping to start a family, wanted to formally defy. I don’t know how much I believed in this goal. More likely, I think, it was a way to move on without actually moving on, rejecting my depressed self while also keeping her close. Watching my brother Jordan check into a Long Island hospital for his own suicidal depression, the project seemed more than anything like a simple intellectual pursuit.

By all objective measures, Jordan’s program was doing everything right. He’d tried a different hospital first, which was more like a glorified holding pen—no therapy, no group activities, the exact opposite of rehabilitative. But this center was more reminiscent of a college dorm than a hospital, with access to a basketball court, an elliptical machine, a piano; a team of doctors, therapists, and social workers; and friends or, at the very least, peers. He was active; he wasn’t alone. He’d talk about throwing a pool party at our parents’ house when he got out, when they all got out.

It didn’t matter. He was still crying every day.

A year earlier, on the morning I walked into the Brooklyn emergency room and said I wanted to kill myself, the hospital was the only option I could see outside of swallowing all the Xanax I’d stashed for as long as I’d been taking it.

I’m checking myself into a psych ward, but don’t call me, I don’t want to talk about it , I sent to our sibling group chat.

Jordan texted me directly, off thread: I love you. Don’t let it win.

When I visited Jordan at his center, I wasn’t allowed to bring my phone. I couldn’t show him his text, proof that he’d once believed, for me, a future which he needed now to believe for himself. So instead, I reminded him, again and again.

“Remember what you said to me,” I’d say, holding his hand.

What I meant was, Remember how you saved me. I am trying to save you too .

*

Don’t let it win , Jordan wrote, and years later I’m stuck on the it . If it is depression, it’s an independent and opposing entity—if it wins, I lose—which is to say a version of depression that doesn’t resonate with me anymore. Partially this is because I’m exhausted by the notion that surviving depression means living through a battle. But on a more basic level, I’ve become resistant to the idea that depression isn’t part of who I am. It certainly feels like it is.

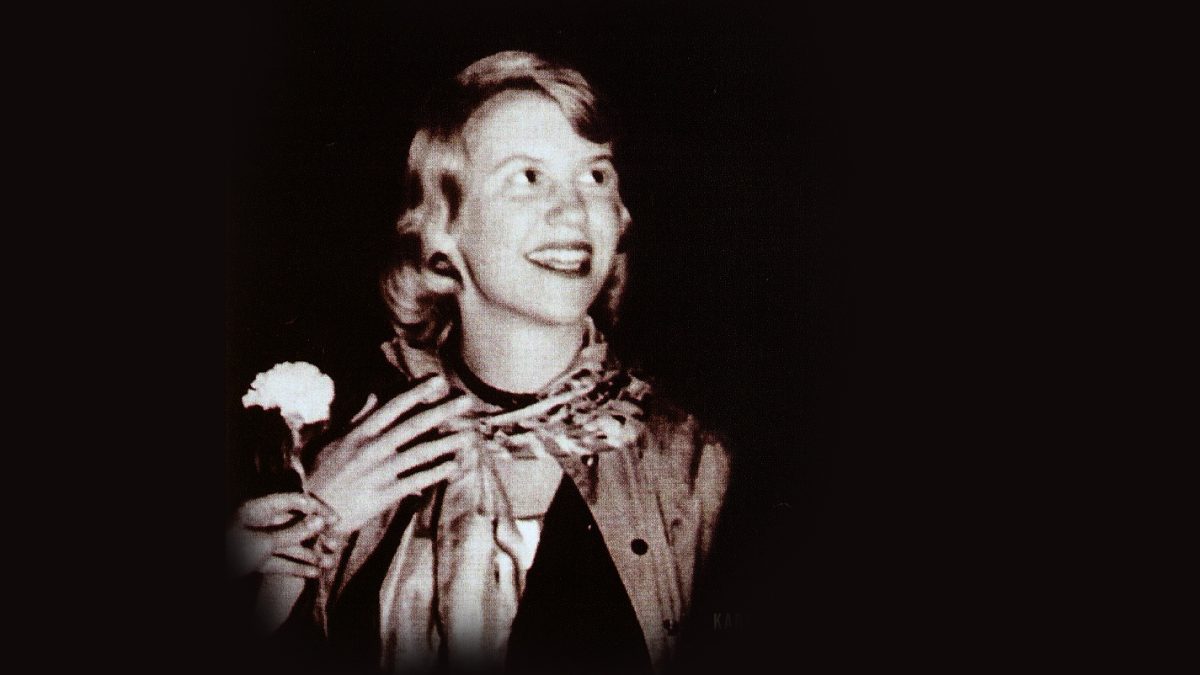

While Jordan was hospitalized, I was deep in Sylvia Plath’s journals and letters, looking for evidence of what went wrong, what failed her. But mostly what I found was a person desperate to write her way out of fear. Attempts to communicate depression and suicidal thinking—to others but also, perhaps more significantly, to oneself—are paradoxically both powerful and insufficient.

And so I wonder when I read Plath’s insistence on separating her depression from herself—by giving it a body, agency, the ability to exert pressure upon her—what power such transferals hold. For Plath, depression is “an old Panic bird sitting firm on [her] back,” “a great muscular owl sitting on [her] chest, its talons clenching and constricting [her] heart,” a multiplicity of “demanding demons.” Surely these descriptors are a means of better describing, and therefore better understanding, this otherwise inscrutable thing, and these comparisons are both common and apt.

Depression can feel like a being that acts at once upon and through me, and when it leaves, it takes all trace of its motivations. When I am happy, it isn’t enough to say I’ve forgotten my depression, or vice versa; I can scarcely believe in it. It may as well have never happened. Outside of a depressive episode, I can know I wanted to kill myself, but I can’t feel it. In its grips, the opposite: Any happiness I’ve ever known was merely misapprehension. We want to explain what depression feels like, so we describe it as an animal, as a demon, a parasite, and then that is how it exists—apart from us, dangerous.

My mother doesn’t rely on metaphor, but the core of her conversations with and about Jordan have always been in passivity. His depression isn’t him; it is being done to him—a parasite, a possession.

“I told him to write a list of reasons to live,” she said during one of our many drives between the Long Island hospital and the hotel I’d turned into a temporary home to make visiting Jordan easier. “The next day I asked to see it, and you know what he did?”

“What?”

“He comes out with two lists, and he says, ‘Okay, here it is, but I also wrote a list of reasons to die.’ And you know what I did?”

“What?”

“I took the pen and wrote in big letters at the top: ‘JORDAN’S DEPRESSION’S LIST.’” I nodded, but she was looking at the road anyway. She continued: “That’s not Jordan talking.”

I think of my sister, Danea, on the phone during one of his worst weeks, when there was no getting through his steadfast insistence that he will never get better: “I look at him,” she said, “and I want to say, ‘Jordan, are you in there?’”

It’s Jordan’s depression, but couldn’t it also be him? What power do we cede by allowing that? We resist the idea that a person’s desire to kill himself could be valid or rational, but how much of that aversion is based on our understanding of depression— a notoriously imprecise area of study —and how much is about our fear of the possibility that a person might just want to die? The stakes are too high to say anything other than a version of no you don’t to a person who wants to kill himself, because we think—we need to believe—that if the suicidal person believes it’s not true, then he won’t follow through. I understand why we hold this assurance with a death grip: This is not you. This is a symptom. But what if it’s both?

Let’s say a symptom manifesting as desire is still desire. Let’s say a person can assess her life and recognize her decision to end it as irrational, and still want to do it anyway. Let’s say that telling a suicidal person that she doesn’t want the thing she wants turns that person paranoid, makes her doubt every emotion she feels, shifts her understanding of herself into something slippery, precarious. Let’s say this disorientation makes her doubt not just her mind but then, too, the world around her, which she now knows she understands through a broken mind. Let’s say the desire goes away, and she thinks, Oh, they were right , but this doesn’t make the desire’s return any less scary, because it’s still desire, and she’s still being told it’s not.

And let’s say that, trapped in this cycle, she decides the only thing she knows for sure is that a large portion of her life is spent in a state of unreality, and she’s exhausted trying to parse the true from the false. And let’s say she doesn’t know if she’s killing the true self or the false self when she does it, but she does it anyway.

Couldn’t we also say, then, that this isn’t you, this is just a symptom is not enough?

*

On January 10, 1953, Plath pasted an image of herself into her journal and wrote to her future self:

Look at that ugly dead mask here and do not forget it. It is a chalk mask with dead dry poison behind it, like the death angel. It is what I was this fall, and what I never want to be again. The pouting disconsolate mouth, the flat, bored, numb, expressionless eyes: the symptoms of the foul decay within.

It’s a photo from just two months prior, during a depressive episode so low she describes herself as having been “beyond help,” intent on killing herself. She contrasts this against “the cheerful, gay, friendly person that [is] really inside,” the self she has finally returned to. This, she’s determined, is the real self, and it’s what she tries to channel throughout her lows, desperate to reach “the core of consistency” that she knows exists within her—that she needs to exist within her.

But the lows destroy that consistency, the “continuity” she desires, because her continuity makes no space for depression, a specter that hovers somewhere between foreign entity and foreign self. Both are unknowable, whether in the past as they’re left behind or in the future as they’re feared. Her real self dies and is reborn with the cycles of her depression: “You are not dead, although you were dead. The girl who died. And was resurrected.”

Plath cleaves herself, and over the course of the twelve years her journals span, we see a waning confidence in her ability to determine the real self versus the fake—the former vibrant and successful; the latter, a shameful failure. At her most depressed, she shifts fluidly from first to second person, trying to ground herself through the act of writing as distinct from the other self she’s writing to: “You have forgotten the secret you knew, once, ah, once, of being joyous, of laughing, of opening doors.” More often, she berates this separate self, coursing through a litany of flaws: “You have had chances; you have not taken them . . . You are an inconsistent and very frightened hypocrite . . . You are afraid of being alone in your mind . . . You big baby.”

The summer of 1953—the summer before Plath’s near-fatal attempt on her life—is a mess of you s and I s, a muddle of desperation and contempt. She begins an undated entry “Letter to an Over-grown, Over-protected, Scared, Spoiled Baby,” and it reads like one side of a bitter lovers’ quarrel. Writing in the first person, she tries in vain to prove her goodness, promising many carefully chosen accomplishments—a list of intentions, but also a desperate attempt at ingratiating herself to her depression, knowing she’s in the midst of possession:

I will learn about shopping and cooking, and try to make Mother’s vacation happy and good . . . I will work two hours a day at shorthand, and brush up on my typing. I will write for three or four hours Each Day, and read for the same amount of time from a reading list I draw up carefully . . . I Will Not Lie Fallow or Be Lazy.

But soon the tone and perspective shift. Her affirmations become directives, less optimistic and more frantic. She delivers a sort of motivational speech, all italicized verbs (“accept, affirm . . . prove your own discipline”) and punchy, capitalized slogans (“THINK CONSTRUCTIVELY”). Plath’s fear is tangible: “You better learn to know yourself . . . before it is too late.”

Her writing is panic-stricken. How could it not be? In the battle between the depressed self and the “real” self, only one can make it out alive. But a theoretical death is impossible, impermanent—a sadness will always return, and, for the depressed person, that sadness can signal so much worse. Within these expectations, life assumes an inherent, ongoing violence.

In her 2013 book, Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It , sociologist Jennifer Michael Hecht often uses “self-murder” in place of “suicide”—a phrasing, along with “self-homicide,” that’s found in philosophical treatises about and against suicide from as early as the eighteenth century, a phrasing that encodes a separation of the person from the act, the actor from the acted upon. It’s a tempting designation, a way to preserve and privilege one aspect of the self. As if one could isolate a healthy existence, a sane existence, a happy existence—what is the opposite of suicidal, anyway?

I can’t help but read a willful, even optimistic, delusion in the term self-homicide . What does it matter who is killing whom when both victim and murderer inhabit the same body, when both die with it? The last sentences Plath writes before she swallows the pills one month later are terse, dire: “You must not seek escape like this. You must think.”

*

I’m sure many people rely on missives to themselves—spoken affirmations, motivational phrases on Post-its, a good old-fashioned journal—whether they are depressed or suicidal or not. One needs a way to combat an inner saboteur, a version of the self that is hell-bent on delegitimizing any evidence of talent or goodness. But separating ourselves from depression, or the depressed self, or the saboteur, becomes an issue of deadly importance. We celebrate the emergence into “better” as if it were a wartime victory. Plath glues her photo to the page like it’s an enemy’s head on a stick, as if it might scare any new depression away. Does it work?

What I know is this: Every journal entry I’ve ever written while freshly out of a depressive episode, high on the belief that I’m out for good, has been followed, eventually, by an entry in which I’m back in those depths. My suspicion is that we are not one or the other. We are both. We have to be. How else to allow for a future in which we can glide through illness and wellness without carrying the magnitude of endless death and rebirth, failure and victory? Could a recasting make it all just a little lighter?

On February 17, 2017, three months before my hospitalization, I opened my journal just past midnight and wrote, Shut up shut up shut up shut up shut up . That night, my depression was physical, unrelenting—jaw tight, head heavy, stomach tense, every bit of my body at its edges— and I wrote, Maybe one state isn’t more real than the other—when I’m happy, this feels fake, and vice versa . By May, I was as obsessed with the distinction between fiction and reality as I was with suicide—a word so heavy with intent and desire I couldn’t risk empowering it in writing.

So crazy to think how close it feels , I wrote. To remember the me who didn’t want to do it. So abstract now. Someone else, I guess. I’m trying, I’m trying, I’m trying.

I tried to explain this to the admitting doctor, how part of the reason I wanted to kill myself was because I wanted to stop hearing the voice in my brain telling me to kill myself. She stopped writing, let her clipboard fall to her side. She asked, with an alarm that signaled this might be more serious than she’d first thought, if I recognized the voice. Did I see the person speaking it? But it didn’t work like that. It was my voice, scared.

When a fellow patient-turned-friend was discharged a few days before I was, he told me he was nervous to leave. “People out there, they don’t understand,” he said. “When I try to explain all the bad shit, they think I hear things, or see things. I don’t. It’s just my thoughts.”

I remembered the admitting doctor. My voice, scared .

When I look back on journal entries from those worst days, I don’t see sadness as much as I see existential panic: Who am I, really? How much is a matter of pathology? How much does my fear of owning this darker voice hinge on a cultural insistence that it’s unhealthy, even unnatural? What if I’m all of it?

*

In the days before his hospitalization, Jordan’s texts, already alarming, became urgent, growing into multiple-paragraph mini-essays, and then into emails. He told us he’d have killed himself already if he weren’t so afraid of dying; he’d have done it if he had a gun. One night, I woke up from a dream of pulling an endless, ever-replenishing flow of razors out of his hand, and I worried it was a sort of psychic message that he’d done it.

Please don’t go yet, okay? I texted him. Just wait a little longer at least .

The next day he texted, I’m already gone. This is just my body.

His life felt empty, made unreal. Life had become foreign, so he let flourish the idea that it wasn’t even a life. Consciously or not, he was nurturing an environment in which it would be easiest to leave: If you’re convinced you’ve already lost a vital aspect of existence, killing yourself is less drastic, and perhaps less scary.

“I wonder about the damage done by constantly imagining your suicide,” my therapist said during one of the many sessions in which I recapped everything that had happened in the past week that I’d responded to with thoughts of suicide.

“Right, like I’m cutting off any possibility of healthy responses to stress,” I said.

“Well, yes, but more so the psychic damage. That fixating on your own nonexistence can actually chip away at your sense of self, or reality.”

In other words, it’s a tenuous border between fantasizing about oblivion and begetting it.

*

David Foster Wallace’s This Is Water —the commencement speech Wallace delivered at Kenyon College in 2005, three years before he hung himself, four years before it was published and packaged for the twee gift aisle—has become a shorthand for mindfulness. But it, too, touches upon the fear of a living death. The speech begins with a parable:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

What follows is a message of compassion, patience, and awareness. Wallace describes the drudgery of adulthood, how quickly one can default to self-centeredness, and how easy it is to get stuck there without realizing it. He worries the message might be written off as “just a banal platitude.” But, he warns, “in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes”—(in this case, that “the most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see”)—“can have life-or-death importance.”

Wallace’s worry is unnecessary; the speech references suicide too often and too casually to fit neatly into “banal platitude” territory. It lends a direness, an urgency, to the otherwise-benign advice: Fail to exercise this awareness and you risk your life. But survival isn’t enough for Wallace; he’s less concerned with physical death than he is with an empty, sort of zombie existence. In one of three references to people “shoot[ing] themselves in the head,” Wallace clarifies, “The truth is that most of these suicides are actually dead long before they pull the trigger.”

What pressure to lay upon oneself—to be ever vigilant, a sentry against a subtle, creeping death. It isn’t enough to live; one must live right . And there is a right way to live, Wallace is sure of it. He’s sharing, after all, the “capital- T Truth” about life. The problem with believing in and living by a “capital- T Truth” is that it tends to be unforgiving. It demands absolutism in a world of nuance. It recasts so many valid experiences as failure.

In this case, the “capital- T Truth” is about “simple awareness . . . of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, that we have to keep reminding ourselves, over and over: This is water, this is water .” Does his suicide mean he failed to maintain such active awareness? Or could it mean he was wrong about its importance?

*

In reading about Plath, in her words and in others, I find myself looking for signs that she wasn’t ever really happy, that she and husband Ted Hughes weren’t ever really in love. I look for something I can use as evidence of a lack that made it easier for her to leave, something I could point to as evidence that my love is deeper, fuller, stronger than hers, which is to say that my love can succeed where hers failed.

I’ve pored over the photos: Plath standing next to Hughes, gazing down at their newborn daughter in her arms. Is her smile tight, her body just a bit distant? Or, later, Plath standing next to Hughes, but here it’s as if she can’t get close enough. His arm is around her waist, and she grasps his hand with both of hers—Look at her fingers! Curled, holding tight!—and her head is lifted skyward, her smile is wide, spreading into her cheeks, her eyes. It’s 1956, seven years before she’d kill herself, and she looks to be in utter bliss. Was her suicide present even then, somewhere deep within her? Could it be something predestined, that final event connected to a thread we might trace through every moment, every decision, every expression?

How comforting it would be to find something that would betray the certainty of her suicide, but instead I find her persistent confidence in her recovery. As it stands, all I can infer is that such confidence won’t protect me. It didn’t protect her. Sometimes I wonder if it was this optimism that was her ruin, if it distracted her from a diligent watch for depression’s return. I think, Maybe the key is never letting it get so far away that I lose touch with it. Maybe the moment I let myself forget that I have depression is the moment I open myself to be destroyed by its return.

But it’s a dangerous thing to build a life and identity around an ailment or a decision or a thought pattern, to morph history into prediction. Maybe the happy medium is in easing my grip on my imagined possible futures—doubling down on neither a permanent betterness nor a predestined descent—and making space for uncertainty, discovery. Maybe it’s giving myself permission to choose belief based in hope rather than fear. “Nothing is real except the present,” Plath wrote in fear, but the statement also holds freedom.

Jordan survived as I survived, as many do: through therapy, medication, support, and the good old-fashioned passage of time. That neither of us has committed suicide yet doesn’t mean we won’t, but neither does our having been close to it doom us to that fate. Survival is continuous; often, it feels like waiting. At best, it’s an amassing of reasons to stick around, trusting that when the impulse returns, if it returns, those reasons will be enough.

*

The morning after I was admitted to Maimonides, I met with my support team for the first time—a psychiatrist, counselor, social worker, and nurse, only one of whom I’d ever see again. I worried that the fact that I hadn’t cried yet would seem suspicious, that I might seem like I was faking it, so I explained I wasn’t really feeling sad; I was feeling nothing. I’d just published my first book, I was in a great relationship—still, nothing.

“Can you tell me something in your life you’re excited about?” the psychiatrist asked.

My instinct was no . But I took a second to sit with it, which is when the sting of tears finally hit.

“I want to have a family,” I said. “But I don’t want to have a family like this.”

I wanted to die, but now I’m not sure if the desire was born out of my depression or of my certainty that having depression made me ineligible for even the simplest joys. I think the distinction matters. I think that might be where resilience lies. I see myself on that morning, in that hospital gown, and I wish I could say, “You can have a family like this. You do.”

But I guess it doesn’t matter. She learned it; I learned it; I’m learning it.