People Relationships

Why I Needed to See the Heart of Padre Pio

An obsession with a Catholic saint and his relics made me think about the pieces of myself I had offered up to others.

I waited in line for an hour to see his heart, eating sausage in a semolina bun with roasted hot and sweet peppers, watching children chase each other around headstones in the church graveyard as live Polka music blared from the bandstand. A line snaked around a gazebo, then under an oak tree, where a statue of Padre Pio stood crooked on the emerald lawn. The woman next to me, an Asian woman with a tidy black bob and bangs, had driven an hour and a half from a rich, horsey suburb of Philadelphia to see Padre Pio’s heart. “You Catholic?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “Not really. I mean, I was baptized.”

“You do catechism?”

“Yes, but I was older,” I said, flashing back to Our Lady of the Rosary, the cathedral in San Diego where my mother had fast-track-baptized me at twelve years old, then thrown me into catechism and First Communion prep classes with kids half my age.

“Communion?”

“Yes, but . . . ”

“Confirmation?”

“No.”

We’d left San Diego before I could be confirmed. The whole year had been my mother’s nostalgic return to the Catholic Church of her Detroit youth, both of which she’d left decades earlier. My childhood was spent traversing California in pursuit of Mom’s next, best spiritual practice, as she cherry-picked what she liked from each to craft her own devotional.

“So why do you want to see his heart?” the woman asked me.

I’d been wondering that myself. “Honestly,” I said, “I’m not sure.”

I had, on a whim, rented a car and driven ninety miles from Philadelphia to Vineland, New Jersey, to visit the heart of a saint I’d become obsessed with the day before. I didn’t know how to tell a person who was clearly an exuberant Catholic that what I was seeking had less to do with Padre Pio and more with a growing ache for epiphany. I was emerging from a deep excavation of myself, fueled by leaving Ramon, my boyfriend of eight years.

At twenty-eight, when everyone else was settling down, I’d left the man whose child I’d helped raise. Who had seen me through the mental deterioration and death of my mother. A man I’d been devoted to for two long-distance years in college, when my peers were hooking up in dark, sticky Tijuana bars. We had the kind of passion that entered and expanded me into an entire universe; everything else was collateral damage. Until, eventually, the fire and the chaos settled, and it became clear that even though I loved him madly, in the grown-up world, we wanted different things.

I tried to talk to Ramon about this. He sat blank-faced and unresponsive. Weepy nights pouring out my doubts to him left me with conversational blue balls. There was no catharsis—none of the fission it takes to shift a partnership. His silence was so disorienting that, over time, I started to question if I’d said anything at all. Still, I stayed. Ramon cooked for me; he painted Technicolor waves and played the radio, told me jokes, perfected homemade pizza. I was waiting for him to acknowledge what I’d said, but he just went on loving me. This dissonance scrambled my desires, what I knew to be true. Maybe I didn’t really feel those things. Maybe I didn’t want to leave him after all.

Losing your voice doesn’t just happen. I needed to figure out how it had happened to me.

After finally leaving Ramon, I rented a tiny one-bedroom in Portland, Oregon. On the surface, I crackled with the energy of the newly independent, partying and dating and discovering the self I’d bypassed in my early twenties. But I was also taking inventory. Cataloging losses. Reopening and examining old wounds, attempting to clean them properly.

It was a seven-year ablution. It wasn’t innocence I was trying to reclaim, exactly, but purity, maybe—purity as in concentration of self . If I was just alone enough, I thought, maybe I could recover and distill my own essence, craft some wearable oil with which to anoint myself, myself .

I began to write during that time, banging out page after page on a rickety Olympia with no delete key. Up she came, the messy river of story long submerged—a story about my mother, and the lines between her mysticism and madness. I suppose I was also writing a letter to myself, asking whether it was possible to reach divinity through my body, not through spiritual practice.

*

While my mother had always chased her own patched-together God, I needed one clear, steady belief. He arrived the winter of my junior year of high school, and his name was Leo: a Bud-drinking fifteen-year-old raised on drain-ditch fishing and BMX. He’d just moved to Dunsmuir, California from Rancho Cordova and loved hunting and fishing. He was a pit bull of a boy, short and stocky, with a shaved head and a gnarly bite.

I consumed Leo like food, like water, like air. My friends called him a cliché. But that was exactly it for me; it was the bravado, the unabashed holler of him, that sent me over the edge. The husk and rumble of his voice hot in my ear activated some primal network in my body, an erotic phone tree, one part ringing another and then another. My devotion was to becoming a body. Upon Leo’s word, I became breast, thigh, leg, vestige of wing.

I stayed with him for four years. At first, I loved the way his thick, ruddy fingers gripped my arm.

*

I moved from Portland to Philadelphia to finish the story I’d started on the Olympia and work toward a graduate degree in creative writing. It was there, at my kitchen table in Philly, doing final edits of my book, that I came across Padre Pio’s name: “I must turn these letters into flagstones; my nightmares into crystal-hung visions of Padre Pio.” During the feverish Portland years, evidently, I’d written the saint into my story—but I had no memory of writing it.

As I chanted the line aloud, my skin prickled. His name became an incantation, a sound I had to pursue. I scoured the web for everything I could find, mostly dead-ending at devotional websites with a community-cookbook aesthetic.

Born Francesco Forgione in the 1880s, Padre Pio was pious by nature. His family, known as the “God-is-everything-people” in their southern Italian village of Pietrelcina, attended Mass every day, prayed the Rosary each night, and abstained from meat three days a week in honor of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel. But even in his devout home, little Francesco stood out. As a five-year-old, he used stones for pillows and slept on the ground. He spent much of his childhood talking to Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and his guardian angels. And he was sick, first with gastroenteritis and later typhoid.

At fifteen, he left home to study with Capuchin monks, hoping to become a friar in the Church. But after a year, he became violently ill and was put on bed rest. He spent days in a trance-like state, calling out to Jesus from his bed.

Jesus one last thing Let me kiss You What sweetness in these wounds! They are bleeding But this blood is sweet, it’s sweet Jesus, sweetness Holy Eucharist Love, Love who sustains me Love, I will see You again soon!

The monks thought he might be dying, but he was in a state of religious ecstasy, an altered consciousness. It was a transcendent awakening, a merger with the God he’d felt called to serve since childhood. Padre Pio spent his entire life in intertwined states of ecstasy and agony—his devotion inseparable from his pain.

As I searched for more about him, I found this headline from the Boston Globe :

Padre Pio Heart Arrives in America Tomorrow

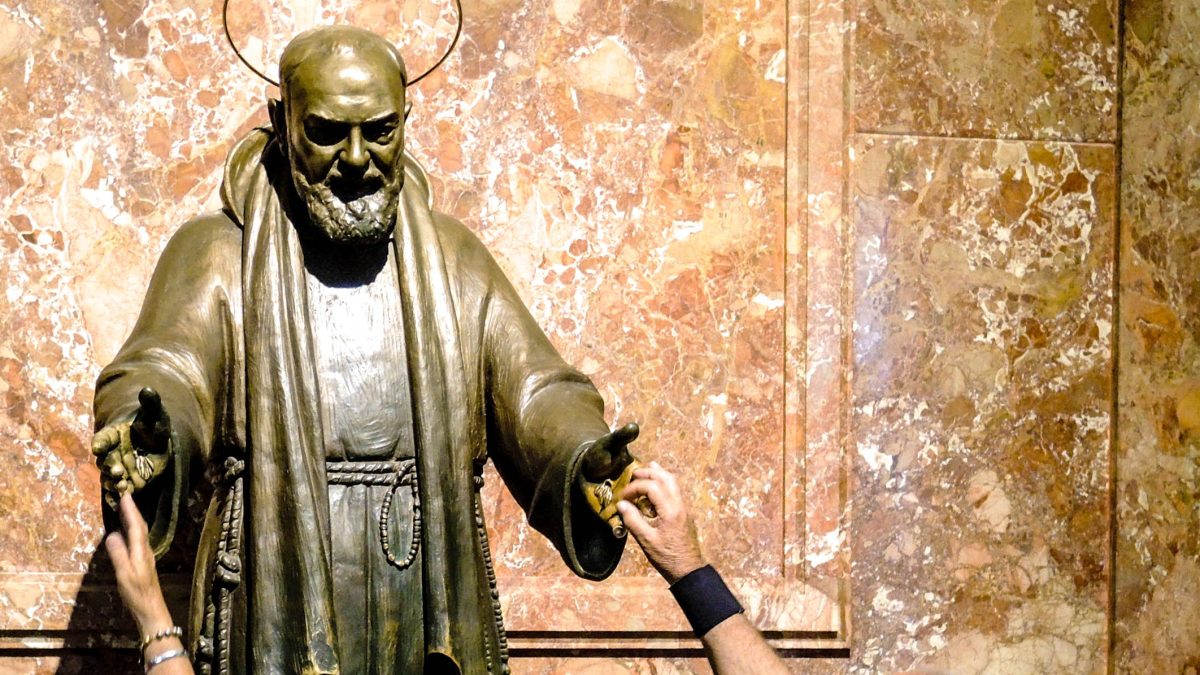

In 2008, sixty years after his death, the Catholic Church exhumed Padre Pio’s body and found it partially intact—or, in their language, incorrupt. They cut the heart from his corpse and deemed it a holy relic, a miracle of preservation. By the time I saw the article, his perfect dead heart had been visited by millions of devout Catholics from around the world, and it was scheduled to arrive at the Padre Pio Parish in Vineland, New Jersey, ninety minutes from my Philadelphia apartment, the very next day.

I fell back in my chair, my mind buzzing with the feverish synchronicity of my sudden search. Pio had been through stigmata, pain, transverberation, endless illnesses and ecstasy. He’d been able to reach transcendence by offering his body, his self, completely. I’d always wished that were possible for me.

I decided I had to go to Vineland to see his heart.

*

“Now, if you touch something to the box,” the Kennett Square woman said, gripping her Rosary, “it becomes a third-class relic. Anything that touches first automatically becomes third.”

Her Rosary was a smoky glass snake curled around elegant fingers. A tarnished silver cross hung from its end. My own Rosary was tucked in my sock drawer at home.

“So the heart is a first-class relic?” I asked.

“Yes. Body parts are all first-class. Second-class relics can be things saints wore or touched.”

The line edged forward and we finally stepped through the doors of the parish. Rows of votives flickered beneath life-sized plaster statues of Mary and Jesus, their heads enveloped by glowing halos. Stained-glass Stations of the Cross filtered sunlight, illuminating the space with watery shafts of red and seafoam green and warm golden yellow. As we shuffled slowly down the aisle, two men, Knights of Columbus, with military-style helmets sprouting plumes of purple feather, came into view on either side of the altar. Between them, a petite brunette woman with a pious slant of a mouth held a glass box on a stick.

“The reliquary!” whispered my new friend.

I didn’t have anything to touch to the box, so I waved my left hand at my new friend, pointing to the brass rings on my middle and ring fingers.

“That’ll work,” she said. “Anything!”

I stepped forward, coming face-to-face with what looked like a tiny coffin full of beef jerky. Donning my most sincere face, I touched a ringed hand to the box and squeezed my eyes shut, sure that the heart of Padre Pio had something to teach me.

After a long, hollow silence, I opened my eyes and stepped aside, instinctively making the Sign of the Cross. The air was milky grey and choked with myrrh, smoke lolling skyward from behind the altar.

What had I expected, exactly? I walked to one of the pews and knelt on a cushioned rail to pray. Rubbing my fingers over the smooth metal of my rings, I thought about relics. What relics of me were out there?

*

Leo began to monitor me in subtle ways: showing up to parties uninvited to make sure everyone knew I was his; slipping in cutting comments about my makeup or clothes until I took to wearing sweatpants and ponytails, makeup-free. These concessions were small markers of my devotion—if no longer to him, then to some deeper need to be owned. How else to explain that, even after graduation, when I was miserable and could have left, I doubled down and moved with Leo to a two-story townhouse in Fortuna.

There, in an old mill town full of retirees and immigrant families, Leo mopped floors at a gym, lifted weights, and drank beer with his hunting buddies. He chewed tobacco and spit the brown sludge into old soda cans with the tops ripped off while skinning deer in the backyard.

I took literature classes at College of the Redwoods and waited tables at the Red Lion Inn. I wanted to write and read and act and dance, but instead I grilled shrimp and vegetables for dinner and cleaned the house on Saturdays, every sacrifice a hollow offering. Obligatory flagellation I couldn’t quit. I was nineteen years old, and watching myself from behind a glass wall.

*

Padre Pio bled silently at first. He was twenty-three and had just become a friar when he first received the stigmata—pain and bloody wounds that mirror the crucifixion marks of Christ. He prayed to Jesus to keep his wounds hidden. He carried the pain of stigmata, but there were no physical manifestations of it for another eight years. For eight years, he was the only witness to this private, invisible communion.

When he turned thirty-one, blood began to flow from the wounds. He bled small streams from the inside of his wrists, the top of his feet, an open wound on the torso. Medical records say he lost a cup of blood a day from the gash in his side, which kept wrapped in cloth underneath his habit. “For nine days nobody knew anything about it,” reported Father Joseph, a fellow monk. “Then, when the friar changing the linen on his bed found blood on the sheets, he told the father guardian, and Padre Pio had to confess to what had happened.”

Over the years, Padre Pio was examined by dozens of doctors, but they never agreed about the cause of his wounds. “Not natural,” one doctor called them. “Supernatural,” said another. “A phenomenon not explained with the sole human science.”

In the book Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, Sergio Luzzatto highlights a correspondence between Padre Pio and a local pharmacist who suggested Pio used carbolic acid to self-inflict his wounds. “Unconsciously self-produced by autosuggestion,” the pharmacist determined. “And kept artificially with repeated applications of tincture of iodine.”

*

I didn’t tell Leo I’d applied to UC San Diego until I got in. In a rage, he broke our lease early to start a summer gig as a park ranger in Garberville. As I sat alone in our apartment packing and purging, I felt like I was emerging from a deep slumber. I watched the form of my hands return as I cooked breakfast for myself and ate in delicious silence. Whatever the past four years had been, I was certain that the girl who had been swallowed was gone for good.

I felt so totally resurrected that when Leo called and asked me to stop for a final goodbye on my drive down to San Diego, I agreed with something like beneficence. As if we were stars in an indie movie and this was our cinematic, bittersweet end to a narrative arc in which I’d reclaimed my spirit, soon to bid adieu—with a final fling—before driving into a sunset of palm trees and self-growth. Yes, the sharp smell of redwood sap, the musty fresh of his cabin, they would bestow some final woodsy closure upon us.

We cooked shrimp scampi. He asked me not to go, said he would change. I was loving but resolute. No, I said. It’s over.

He said it was an accident when he came inside me. I knew I was pregnant immediately. I’d almost felt him will it. Leo’s urge to own me was nothing new, but my choice to be with him that night was devastating. On the knife’s edge of reclaiming my life, I’d welcomed back the narcotic bliss of takeover.

*

Kneeling in the pew after seeing Padre Pio’s heart, I remembered the men I’d dissolved into. All those years, I’d assigned Leo credit for delivering me to my body. The particular timbre of his desire, and mine for him, had built a sort of home in me—a way in which in some men can talk to me today, using a crude language of ownership that isn’t aligned with my politics, but still, in private, I quiver. I can still feel Ramon’s fluid swagger flooding me with such full-body ecstasy that I let it, for years, override his refusal to truly see or care for me.

For me, both sacrifice and ecstasy were better in private, where I could live out my contradictions unseen. I understand why Padre Pio wanted to suffer in silence: He could enjoy the release of sacrifice without the spectacle of public bleeding.

Just before I’d moved to Philadelphia for grad school, I had a birthday party. “Wow, thirty-three,” said my friend Alissa. “The Christological year. The year you find out what you’re willing to die for.”

I thought then about the bodies of the men. As a girl, I’d discarded the theological pastiche of my mother’s spiritual life as too chaotic, but I’d clung to the idea of self-martyrdom as a channel for ecstasy, transferring mine instead to something tangible: the most concrete bodies I could find, men of mud and earth. I made these ordinary men into small gods, unable to see what I was actually seeking—a restoration of faith, through the body.

I see, now, the danger in calling surrender sacred. I see why Padre Pio’s name sung out to me from my own story.

After an abortion I didn’t tell Leo about, I thought I was free. But even as I rebuilt myself at UC San Diego, studying literature and writing, I had flashes of yearning—for the flooded senses of girl-just-born lust I’d felt with Leo; for the rough of his hand against my back. It seemed to come in waves, this reaching back, at critical moments.

When I was closest to landing on my own path, it would kick in. Instead of making conscious, difficult choices to craft and hammer a life of my own making, I sometimes ached to be spun through a cyclone that would obliterate my dreams, ambitions, boundaries, and sense of self. It was a pattern that would replay later with Ramon, and others after him.

How many times had I yearned to hand ownership of this vessel to someone—something, anything—else? A god, a man, a baby, a drug, a dance. Like young Francesco, I got high on offering myself for consumption.

*

Stigmata is considered a religious miracle and a personal communion because the wounds parallel those of Christ, allowing the recipient to share his body and blood. St. Francis of Assisi carried the first documented case of stigmata in 1227, and since then, the Church has recorded close to four hundred other cases. Yet only sixty of those stigmatics became recognized saints. The rest were simply people who, the Church believes, gained access to God through their bodies. Some of us only learn this way—by dismantling the self and gouging out its borders.

Most scholarship about stigmata focuses on whether the wounds are divine. In Padre Pio: The True Story , Bernard Ruffin writes, “For every genuine stigmatic, whether holy or hysterical, saintly or satanic, there are at least two whose wounds are self-inflicted.” But maybe divine origin is not the point.

Before I drove to Vineland to visit the heart, I’d been asking myself whether it is possible to achieve divinity through the body. But kneeling in the pew that day, I realized there is no other way. The body is our only vehicle for ecstasy. The culmination of Pio’s physical devotion to God was his body divided, his parts strewn around the world as relics. I’d made gods of these ordinary men, wanting to believe my physical offering was an act of devotion, and like Pio, parts of me were left with them. Rubbing the cold brass of my rings, I wondered: How many times can we offer ourselves for consumption without also becoming relics?