People The Blacklist

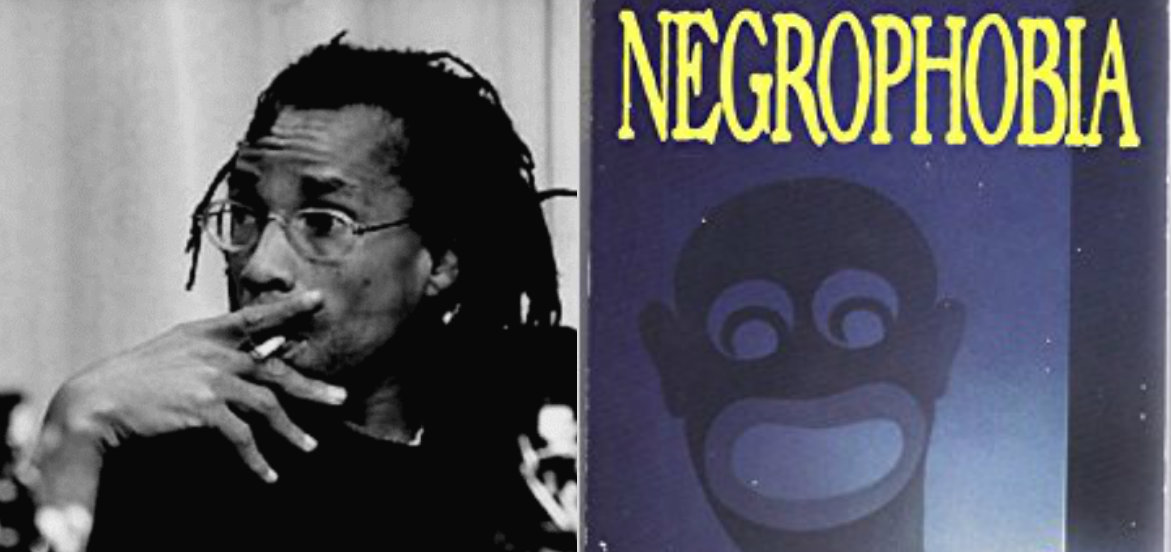

“Negrophobia”: A Novel by Darius James

Published in 1992, “Negrophobia” was a wild romp through a racially charged dreamscape.

This is The Blacklist, a monthly column by Michael Gonzales exploring out-of-print books by African-American authors.

Thinking back to those childhood days in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I was often in the living room propped in front of our oversized black-and-white television set. Many film and television images that would be deemed as offensive today were still a part of our everyday world in post-civil rights America. While Martin Luther King might’ve gotten us a literal seat on the bus and at Woolworth’s lunch counter, that didn’t stop American icons Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben from staring at us from supermarket shelves, or the occasional Warner Bros. cartoon that featured kooky Africans, a hell-dwelling Sambo meeting with Satan on a Sunday morning, and jitterbugging darkies dancing through the streets of Harlem. With titles that included “Uncle Tom’s Bungalow” (1937), “Jungle Jitters” (1938) and “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs” (1943), these shorts were shown before the feature films.

After the advent of television, those same cartoons, mostly done for the jazzy Merrie Melodies imprint, were syndicated by local stations and shown across the nation. Although racist cartoons with negative images of Black folks were at one time a small part of a pop culture landscape, the most notorious of these cartoons, as I learned from reading Cartoon Research columnist Christopher P. Lehman’s series on racist cartoons, are referred to as “The Censored 11” and were pulled out of television syndication circulation in 1968.

For better or worse, these negative images spilled over into black pop culture and have inspired various artists. We can see the tar brush strokes in the paintings of Michael Ray Charles, in the laced joint of Spike Lee’s bizarro Bamboozled, in Miles Marshall Lewis’ southern rapper minstrel short story “The Wu-Tang Candidate” ( Bronx Biannual, #2) and, most recently in the animated video directed by Mark Romanek for Jay-Z’s provocative “The Story of O. J.” The clip shows the self-proclaimed King of New York has adopted the notorious Sambo persona, flipped it to an autobiographical Jaybo , and created a clip that was controversial for both visual content and lyrics.

In a Village Voice cover story essay The Politicization Of Jay-Z, writer Greg Tate reported that the video ticked-off the “Black cultural nationalists with zero tolerance for irony, who now want him tarred and feathered for portraying Nina Simone and Huey Newton as minstrel acts . . . everybody talks about the white gaze of white supremacy, but damn if he didn’t throw it up on the screen in buck-and-winging black-and-white.”

As I read Tate’s words, I scratched my nappy head, took a bite of watermelon and wondered why someone didn’t contact my homeboy Darius James, author of Negrophobia, a novel as inspired by the bang-zoom zaniness of those cartoons as it was by the writings of Amiri Baraka and William Burroughs.

*

Published in 1992 by Carol/Citadel Press, Negrophobia was a wild romp through a racially charged dreamscape that zipped from one absurd scene to another so quickly, you didn’t have time to question the illogical logic as stereotypes Uncle Remus, metal lawn jockeys, African cannibals, and Little Black Sambo plowed through the pages. “Growing-up in the ’60s, I watched all of those cartoons, but I didn’t associate those images with me or any other black people,” James said to me last year from his home in New Haven, Connecticut a few days before Christmas. “Though I was aware that that was how white people might think of black people.”

At sixty-three years old, James is a divorced former expat who lived in Berlin for over a decade before returning to the states in 2007. With a wicked sense of humor, he chuckles often. Having read and performed his often brilliantly off-color material for years, his speaking voice is clear, though it sometimes reminds me of our shared hero, Richard Pryor. Raised by a mother who was a psychiatric nurse and a painter father whose abstract expressionist canvases hung throughout the house, James’ first artistic inkling when he was a boy was to become a visual artist.

“I did some painting, but my father’s criticism was so harsh that I started writing instead, because he didn’t know anything about that.” Reading widely from the time he was in fourth grade, James devoured his mom’s Freud and Jung textbooks as well as underground comics drawn by S. Clay Wilson and Robert Williams, the novels and poems of Chester Himes and Ted Joans. “I also watched tons of television,” he said. “Children’s programs hosted by Sandy Becker and Soupy Sales were my favorites. It was like a pre-drug thing. Those shows prepared you for the reality of LSD.”

The avant-garde black power works of Amiri Baraka were also an inspiration, but years later the noted writer was far from impressed by the Negrophobia pages he read when teaching at Yale in the ’80s. “Baraka was running a writer’s workshop, but neither he nor any of the other students were very supportive. They basically told me not to publish it. To go away and don’t publish it.” In the final text of his debut, James got his revenge by referring to Baraka’s novel, The System of Dante’s Hell (1965), as “shit-stained pulp.”

In James’ black (face) comedy horror, written in the form of a screenplay, the anti-heroine protagonist was a racist white teenager named Bubbles Brazil, a spoiled little rich girl who was so badly behaved that she’d been kicked to the curb by every private academy in New York City and placed at Donald Goines Senior High School. “What’s a white girl to do in a school full of jigaboos?” Bubbles wondered.

Back home, after smart-mouthing her “kerchief-headed . . . meaty-arm” servant, a grits-cooking maid who resembled a 1950s tele-domestic, the woman put a serious mojo on the young girl that sends missy hurling into a hallucinogenic dark place, a voodoo so vexing that it is hard for her to get out. “The maid slithers into a convulsive snake dance, foams at the mouth, and tears off her clothes,” James wrote. “Fish-eyed pancakes are slung Frisbee-style across the kitchen. Bruce Lee’s kung-fu cat cries mingle with James Brown’s R&B funk shrieks.”

For the next hundred-fifty pages, Bubbles bounces like an ivory-hued pinball from one surreally racist scenario to another. In my mind, the words became pictures in the style of P-Funk cover artist Pedro Bell. In addition to the race issues, Negrophobia is sexually graphic and filled with enough free-flowing bodily fluids to gross out the strongest stomach.

The idea to write his wild styled book came to James when he was living in the West Village in the late ’70s. “It was just as simple as putting the words ‘Negro’ and ‘phobia’ together,” he said. “The Bubbles character was based on a few different women. There was this one white girl from West Virginia I knew who, after her parents split-up, was forced to go to Martin Luther King High School, because her father wouldn’t pay for private school anymore. She would tell me these crazy stories that I thought were so funny.” Originally written in traditional narrative form, after his friend and neighbor Michael O’Donoghue, the National Lampoon writer and Saturday Night Live original cast member, suggested he compose it as a screenplay, the ideas finally gelled.

“I knew it would be the best way to avoid a lot of psychological jabber about the characters,” James said. “I just wanted the reader to deal with the images and therefore confront those same images on their own terms.” Taking ten years to complete the manuscript, James worked as O’Donoghue’s researcher on various film projects, including Biker Heaven, the proposed sequel to Easy Rider that, according to Splitsider.com, “was set in 2068, a hundred years after the original, and saw the original movie’s main characters resurrected by ‘the Biker God’ to recover the original Gadsden flag in the wake of a nuclear war, as they encountered numerous biker gangs.”

Negrophobia has been championed and ridiculed by critics and readers alike, with a strange array of celebrity fans that includes actor Johnny Depp, members of Fishbone, and painter Kara Walker, whose use of slave imaginary in her famed silhouettes has been called “revolting and negative” by assemblage artist Betye Saar. “I read Negrophobia in 1994, when I was just about to graduate from the art school, and I’ve dealt with it intensively,” Walker said in db-art in 2004 . “It was one of those rare soothing moments that I thought there could be another person in the world who understands what I do.”

The book’s biggest critic, however, was an employee of James’ publisher who believed the cover promoted the same stereotypes it purported to be combating and tried to have it squashed. Florence Washington, a black administrative assistant in Carol’s New Jersey offices, was offended by the image which showed, as The New York Times described in the June 17, 1992 Book Notes column, “a white girl, scantily dressed . . . over her shoulder is a shadow of an oversize Sambo-like caricature that resembles racist art from the 1930s and 40s.” Designed by art director Steve Brower, he and Darius, “saw the picture as a visual representation of the novel’s basic satirical line: What the teen-ager sees over her shoulder is not the shadow of a real man but of her deepest fears.”

Washington claimed she was going to report the incident to civil rights activist Sonny Carson. “The worst part was, she hadn’t even bothered to read the book,” James said. The protest didn’t trigger any bans or burnings, but it did generate the NYT piece. James told reporter Esther B. Fein, “These stereotypes have not died; they’ve just been transformed and modernized. The whole point is that I believe black people should start taking back these images from our iconography that have been stolen and corrupted through the years by racists. I understand that these images were once oppressive. But I think we are at the stage where we can look at these images and not feel threatened. All kinds of black artists have started to take control of these images, whether they realize it or not.”

Los Angeles Times book critic Dany Laferrière wrote in December 1992. “I opened James’ book only to topple into hell . . . Negrophobia remains the courageous effort of a young writer to understand his time, and a mad attempt to renew the genre of the novel.”

Kathy Acker was the first professional to encourage James after she read the first forty pages of Negrophobia in the mid-eighties. Acker constructed books, including Kathy Goes to Haiti (1978) and Blood and Guts in High School (1984) that were genre-breaking texts that combined word collages, plagiarized text, violence, and erotic (bordering on pornographic) imaginings designed to expand the possibilities of what the novel could be. It was that uncompromising attitude that Darius James applied to his own art that would become associated with the then creatively striving community of writers, painters, filmmakers, performance artists, and musicians who congregated on the Lower East Side.

“The Lower East Side didn’t really start for me until I met Kathy,” James said. The two connected when James was thirty and, after living in the West Village for a few years, had returned to his native New Haven. Bored one afternoon, he looked up Acker’s phone number and cold-called her at home. “I just told her how much I enjoyed her writing and how she reminded me of a jazz musician in the way she handled language and story and identity.”

Instead of being creeped out, she invited him to come see her the next time he was in the city. The following week, he, Acker and writer Patrick McGrath had drinks in an East 5 th Street bar downstairs from a police station. “I showed her those early pages and she read them right there. She told me she thought it was fantastic.” Although the recorded history of ’80s Lower East Side is often whitewashed, there was a thriving community of black artists as well, which essayist Jennifer Jazz described perfectly in her piece Black Like Basquiat: Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Black Kids in Downtown NYC .

James began hanging out at various spots on the Lower East Side including the performance space Neither/Nor where he befriended fellow black writers John Farris ( The Asses Tale ), Steve Cannon ( Groove, Bang, and Jive Around ), both who became mentors, and Norman Douglas. Junkie playwright/screenwriter Miguel Pinero also hung out there, shooting smack in the back with his Sing Sing buddies. A few blocks away, Jean-Michel Basquiat was painting, David Hammons was concepting, and Ornette Coleman was blowing his horn.

“Darius and I hit it off from when we first met,” Douglas said recently. “We read poetry at Life Café and drank at the Horseshoe Bar on 7 th and Avenue B. Greg Tate was the big black culture writer at the time, but I thought Darius was always the more radical thinker and writer.” With Acker’s help, Darius first published in the scene’s infamous literary journal Between C & D, edited by former couple Joel Rose and Catherine Texier. Printed on dot-matrix paper and sold in ziplock plastic baggies, contributors included Acker, Bruce Benderson, Gary Indiana, Tama Janowitz, Patrick McGrath and Dennis Cooper.

*

While I imagined that James would’ve had a difficult time selling Negrophobia to an America publisher, the opposite was true. “I met a New Yorker writer at Michael’s house named George W. S. Trow, and we became friends,” James explained. “He introduced me to the editor at Carol, whose name I can’t remember, but I do recall he was a Deadhead.” In 1993, the book was published in paperback by St. Martin’s Press as part of a deal Darius worked out when selling his nonfiction That’s Blaxploitation!: Roots of the Baadasssss ’Tude (Rated X by an All-Whyte Jury) .

It would take me another twenty-five years to actually complete Negrophobia, and that was only after writer and Man Booker winner Paul Beatty ( The Sellout ) playfully shamed me after I confessed to only reading a quarter of the book when it was released. As we stood in the rain after John Farris’ memorial service in April 2016, Beatty shook his head as though disgusted. “Go back and read that book. You won’t regret it.” When I told James the story, he laughed. “It’s not an easy book to finish,” he told me. “Most people stop at the scene where Bubbles is puking up worms, so, I understand.”

Negrophobia has been out of print since the ’90s, but Beatty reprinted an excerpt in Hokum: An Anthology of African-American Humor in 2006 . “I found the work of the novelist Darius James while passing through Cathy’s bookstore on Avenue B and at the Living Theater on Third Street, hearing him deliver voodoo shibboleths as unruly as his stringy dreadlocks,” Beatty wrote in the book’s introduction, which was reprinted in The New York Times in January 2006.

I finally dived knee-deep into the textual boogie of Negrophobia and was delighted that I did. As Richard Pryor once said, “The water’s cold . . . and it’s deep too.” Darius’ writing style was as vivid as it was precise as he piled crazed images on top of one another. After reading the first few chapters of Bubbles’ Adventures in Darkieland, I took a nap and had a multicolored nightmare of skyrockets blasting in the sky as Mickey Mouse’s dog Pluto bounced upside down, dragging his long tongue along the glittery ground. Seriously, it was as though the words worked a spell on my imagination, and even in sleep they wouldn’t let go.

After the release of Negrophobia, James hoped to begin working on his second novel The Last American Nigger, but life had other plans. “I think we all just assumed that when Negrophobia carried his work beyond Manhattan, Darius was going to be a star,” writer Dennis Cooper wrote in 2007, “an avant-garde superhero writer a la Burroughs and Acker. But his raucous style and subversive mode of confronting racist attitudes by embracing racist stereotypes were frequently misunderstood at the time. Despite the hubbub and some great reviews, the novel was not a big success.”

In 1998, Darius relocated to Berlin, which, in his words, was much like the Lower East Side in the ’80s. While Negrophobia didn’t get Darius’ face in any Dewars scotch ads, his dangerous visions expanded the limits of speculative fiction, and it took me back to the days when I was a teenage geek discovering the alternative new world universes of Harlan Ellison, Ishmael Reed, Philip K. Dick, J. G. Ballard, and Samuel R. Delany while simultaneously blaring the sounds of Prince, David Bowie, Grandmaster Flash, and Donna Summer in the background. An obvious literary pioneer in what the kids today call Afrofuturism, his work has inspired others, including the Ego Trip crew, writer/editor Bill Campbell ( Koontown Killing Kaper ), Hype Williams videos , and graphic artist Tim Fielder, who once did a comic strip insert with him for Between C & D.

Negrophobia remains the most blackadelic funk novel of late twentieth century that has much in common with the various generations of avant-gardists, free jazz cats on stage at Slug’s and doo-rag Dadaists as it does with James Brown’s brand new bag, Ralph Bakshi’s cartoons (especially the apt titled Coonskin ) and George Clinton’s aural acid adventures in Chocolate City. Currently, Darius James is working on various projects, including editing a book project with photographer Gerald Jenkins, discussing a graphic novel with Casanova Frankenstein, composing a spoken word project with Haitian electronic voodoo musician Val Jeanty, and working on a new novel tentatively called Acid Fairies.

“I wanted to write about black women doing acid,” James said. Knowing his work, something tells me there’s more to it than that. For now, I’ll turntable scratch the words of Dennis Cooper, who wrote in a 2007 blog, “Darius may be a slowpoke, but he’s one of the most gifted contemporary American fiction writers in my opinion, and Negrophobia is a singular mindblower of a novel that I think you should do yourself the favor of reading.”