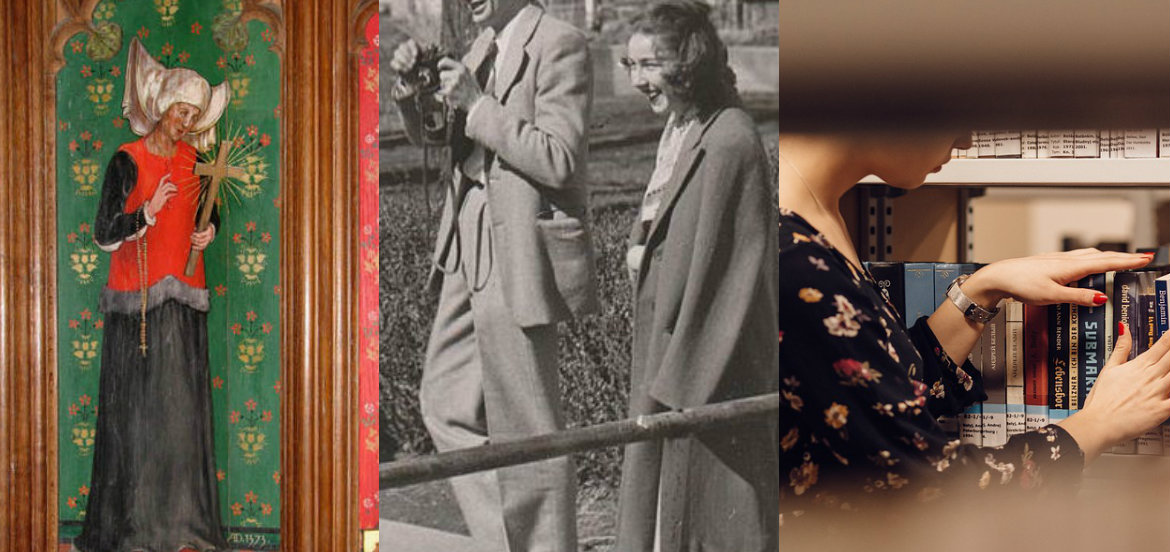

People Believers

Freeing Myself from Grad School, I Rediscover Flannery O’Connor and the Medieval Mystics

I try to use my master’s thesis as a way to find myself in women’s writing—the mystics, Flannery—but, ultimately, I fail.

Here’s a timeline: in 1373, Julian of Norwich writes a list of revelations after a near-death experience. In the mid-1430s, Margery Kempe pens a book about her life. In 1946, Flannery O’Connor starts keeping a record of her prayers. In the fall of 2015, I start writing my master’s thesis.

At the time I begin my thesis, I’m living in Brooklyn, and I’m excruciatingly sad. I live in a split-level house where I rent a room so small that, while sitting on my bed, I can touch all four walls at once. Three semesters into grad school, I propose a thesis I never expected to write—on Flannery, Julian, and Margery. Two of these women—Julian and Margery—met one another, and wrote two distinct texts that I’d found myself returning to again and again as a student of medieval literature. Flannery O’Connor was a Southern writer whose work I hadn’t read. Why did I choose to write about the three of them together? Why did I feel like I had to write about them?

Let’s take a step back. The year I start graduate school, I discover Flannery’s prayer journals. Flannery O’Connor wrote down her prayers as if they were conversations with a very close friend, because they were. They’re intimate and earnest and incredibly funny. At this point in time, I’m up to my eyeballs in texts written by people, mostly men, who never saw the other side of the fifteenth century, and I’m looking for something else. Then, Flannery’s journals. This woman whose diary entries took the form of prayers—I find them, and I’m overcome with homesickness for the South. I’m caught by her humor.

In this way, I find it—a tether. A way to connect my newfound love for a twentieth-century writer from the American South to writers from Late Medieval England, right in her prayer journal: Flannery writes, “Oh, Lord, make me a mystic, immediately!” And I know I have to write about Flannery O’Connor.

The medieval mystics were a group of (mostly) women who experienced some form of direct communication with God, usually through visions. That’s the dictionary definition. To me, mystics have always been a point of fascination. I wanted to know everything about these women, and I kept copies of Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love and Margery Kempe’s Book of Margery Kempe on my nightstand. To me, on the most basic level, every mystic’s story is a story of trauma.

Back in 2015, I feel trapped in academia at a time when I’m trying to fully confront my own trauma. I try to use my master’s thesis as a way to find myself in women’s writing—the mystics, Flannery—but, ultimately, I fail. Now, three years after I deliver a thesis presentation I can hardly care about anymore, I visit Flannery O’Connor’s childhood home and the farm on which she died. This helps more than years of research ever did. It gives me the space to write about the ways in which we all (Flannery, Julian, Margery, me) try to understand our experiences.

Back in my small room in Brooklyn, I often think of Julian, who lived as an anchoress in Norwich. Anchoresses lived, confined, in a small room connected to the side of a church. She would have had two windows—one connected to the church through which she could receive food and confess her sins, and another facing the outside, so she could provide spiritual guidance to her community. My small room has a window that faced an alley.

I spend my days automated: class, work, therapy, class, and, finally, back home to my anchoritic cell of a room. I don’t sleep, I eat too much. I call my girlfriend crying, I nearly walk into traffic because my mind is nowhere to be found. A doctor puts me on antidepressants that make me hallucinate, but taking me off of them is even worse. But most of all, I read. I start collecting my mystics:

In 1373, on her deathbed, the medieval mystic Julian of Norwich dreams that she recreates Christ’s wounds on her own body. Julian is thirty-one. In her fever dreams as she awaits death, she sees Christ—graphic images of his crucifixion and death. She calls them “showings”; miraculously, they restore her health. Thinking about trauma, I ask questions about her mystical experience, her closeness to death. I ask: What happens when your traumatic life experience is death? What is it like to remember dying?

Margery Kempe is another medieval mystic, who refers to herself only as “the creature” and cries uncontrollably in the streets of her small English town, Bishop’s Lynn. Her visions of Christ’s suffering consume her body and her mind like a possession. She doesn’t eat, she denies pleasures of the flesh; she has no body or self, there is only “the creature”. She meditates on suffering.

Religious figurines that sat by Flannery’s childhood bed. Photo courtesy of the author.

I write about Flannery O’Connor, that modern mystic, whose characters loved God so much they became mutilated, disfigured, and deformed. Flannery O’Connor writes, “in some medieval paintings . . . the martyr’s limbs are being sawed off and his expression says he is being deprived of nothing essential.” Flannery, who walks around on her farm among the peacocks, metal braces supporting her body, writes, “I do not know you God because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside.”

Writing, I think about Flannery, and I wonder–what is it like to disregard the body? How do we get around ourselves when we are always in the way? In college and grad school I spend my time skimming fourteenth-century texts for throughlines to my own trauma. Medieval literature is often considered distant, antiquated, unrelatable. For me, medieval literature has always been a way to understand. Flannery is something else, a writer I discover way too late in my short life, whose work placates my growing homesickness for the South. In Flannery’s words—her fiction, her essays, her prayers—I find comfort in a grotesque portrait of a place that raised me.

Spanish moss in Savannah, GA. Photo courtesy of the author.

Julian, Margery, Flannery. These women become my best friends, my bloodline. The thing you have to understand about Flannery O’Connor and medieval mystics is that they’re all women trying to find a way around their own bodies, through their trauma, toward God. And I don’t know if I’ve been trying to move toward God, or what, but I am always trying to move around and through something.

In 1310, before being burned at the stake in Paris, Marguerite Porete writes A Mirror of Simple Souls. Because she’s a woman with radical ideas about theology and God, the book signs her death warrant. Porete tells us that we can make ourselves so small that we disappear into the divine; she tells us that there is a union with God that destroys the self. She tells us about nothingness, how to get beyond ourselves. Her book is an instruction manual for getting around ourselves when we are in the way, and I wonder if Flannery ever read it. I think about what it must have been like, for Marguerite. Her body must have burned so slowly.

*

It gets better, with time, as most things do. I keep going to therapy, I move into an apartment with my girlfriend, and I don’t feel as sad as I did before. My thesis is done, and in the end it feels like any other paper turned in for a grade. So it goes. Then I move, again, back down South. I’m still stuck on them, the mystics and Flannery, I think about them all the time. I read and read and read, and I try to write about them in a way that’s unbound by academic rigidity. I decide to go to Flannery, to her home in Georgia, which is now a day’s drive from me. I see her childhood home, on East Charlton Street in Savannah. I imagine her walking with her peacocks on her mother’s farm in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Flannery’s childhood home in Savannah, GA. Photo courtesy of the author.

Flannery’s mother’s farm in Milledgeville, GA. Photo courtesy of the author.

Flannery O’Connor’s childhood home is a three-story Victorian nestled in the Historic District of Savannah, Georgia. Across the street, you’ll find Lafayette Square, with its large, twisted oaks dripping with Spanish moss and an ornamental fountain accented with oxidized copper. On the opposite corner, facing both the square and the home, is The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. It’s a great, looming thing, and Flannery’s mother’s bedroom stands facing it. We learn this during a thirty-minute tour of the house, given by a woman who talks about Flannery as if she’s having a conversation.

It’s fitting, the manager of the house tells us, that Flannery’s house faces the cathedral. There are so few Catholics in the Southern sea of Baptists, of course Flannery O’Connor grows up in the shadow of a gothic cathedral.

Flannery feels so out of place. You can feel it in her writing, that placelessness. She spends twelve years in her childhood home, before moving to Atlanta, then Iowa, then back to her mother’s farm in Milledgeville—a place she hated, resented. She writes her best work on the farm, among the peacocks.

I’m working backwards, against the grain of Flannery’s life. We go to her home in Savannah, but we visit her farm first. Milledgeville is a small blip in the middle of Georgia, about three hours west of Savannah. There’s a surprisingly bustling highway, a Starbucks, a small liberal arts college. But on Flannery’s farm, it’s 1964. When Flannery dies, of Lupus at the age of thirty-nine, her mother locks the doors to the farmhouse and never goes back. For years, under private ownership, the farm stands still. It’s taken over by nature. It’s an utterly grotesque landscape, even now as the restoration work begins. When we go, we’re given free reign to explore and take photos. The farm isn’t open the public, we’re told by the manager of the estate, but he allows us to take photographs of the land and the exterior of the house. We see the old dairy farm, the calf barn, the lake. I take a close photo of the farmhouse’s front steps—chasing the angle you see in a famous photo of Flannery, where she stands on the steps with her peacocks.

During these trips, I feel a closeness to Flannery I’ve been chasing. These two places—old city Savannah and rural Milledgeville—are the beginning and ending to Flannery’s short life. I get to feel the latticework of the lace quilt on her childhood bed, the view of her garden from the hall. I see her childhood in small details: the dusty hair pins on the mantel, the Virgin Mary figurines on her mother’s vanity.

And on the farm, I see her isolation. Trapped by a disease she couldn’t control, she writes much of the work that would come to define her. She writes and writes and writes until the day she dies, and the farm just stops after she’s gone. Everything just stops.

“I see the dusty hairpins on the mantel.” Photo courtesy of the author.”

“The Virgin Mary figurines on her mother’s vanity.” Photo courtesy of the author.

Did Flannery learn to push herself aside? Did she achieve that nothingness, the kind that Marguerite said would bring her closer to God? Did she ever become a mystic? It’s odd, because standing on Flannery’s farm, I think of Julian of Norwich. I honestly don’t expect it, to feel that connection I wrote about in my thesis a year ago. But I’m standing there, facing a farmhouse built in 1852, and I’m thinking about Julian in her tiny cell where she lived as an anchoress. Julian is administered her last rites in 1373, when the priests assume she’s near death. She’s thirty-one. Flannery is confined, in a different way, on her farm in 1952. Nearly 600 years apart, these women help me find different parts of myself that I’ve lost. I find myself in Flannery’s bedroom, on her farm. I find myself inside Julian’s visions. I start collecting mystics because these women represent a feeling that doesn’t have a name, and I spent years feeling so much emotion that therapy or writing couldn’t help me identify, much less help me grapple with. But Flannery and these mystics, they’re looking and looking and looking, and sometimes the answer is God and sometimes it’s not. Sometimes it’s fire, or peacocks, or wounds. Sometimes it’s abject humor at not being able to find it at all.

The complete line in Flannery’s prayer journal reads: “Oh Lord, at present I am a cheese, make me a mystic, immediately! But then God can do that—make mystics out of cheeses.”