Arts & Culture Art

Why Create Art When No One Will See It?

Fritz Kistel was a reclusive artist who produced a body of work so fabulously unproductive—in the capitalist sense—that I can’t help but admire him: He created for himself.

On the Timeless Island, there are eight zones, eight bands of people, and eight different species of dragon. Riacrons, Dragees, and Dragonturtles stand between four and eight meters tall, while the diminutive Riverfolk could fit on your lap. In the center, there is a deep depression; along the edges stand the Mountains of the Mist, which rise to a height of 4,570 meters, exactly. The last eruptions from the numerous volcanoes, now dormant, were two decades ago, though the “New Lavaflow” still occasionally paints an orange trail through the valley.

Far from there, wherever “there” might be, is the town of Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, Québec, which sits on the northern shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. Ste-Anne has a population of around seven thousand people and lies between the rocky edge of the Saint Lawrence River (which is so wide at that point that everyone calls it “the sea”) and the mountains of the Parc National de la Gaspésie (which in fact is not a “national park” at all, but a provincial one, because—despite the wishes of the waning separatist movement—Québec is not a nation).

Many summers during my childhood, my family drove twelve hours north from Boston to visit Ste-Anne. My stepdad had grown up there, and his mother and father still lived in a house overlooking the beach. The summer I was fourteen, soon after our arrival in Ste-Anne, I noticed something new: a handwritten sign, posted to the fence next door, which read “Jeronimo’s Timeless Island” and showed an arrow pointing down the driveway.

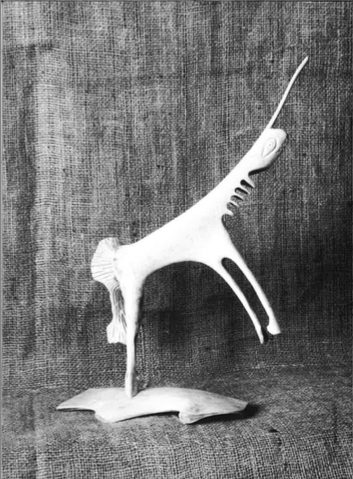

Jeronimo, it turned out, was the pseudonym of a German sculptor named Fritz Kistel. In his cramped studio, he kept hundreds of creatures of wood and bone and antler: some that looked like humans, some like giants or dragons, some with few earthly features at all. Each had a name, some which suggested their characteristics (“Riverfolk,” “Dragonturtles”) and others which very much did not (what does a “Boigon” look like?).

It quickly became clear that Jeronimo was a recluse in the French-speaking provincial town. He spoke none of the language, had no friends or family, and suffered from diabetes so severe that it progressively took away more of his movement. Despite that, he would walk every day on crutches along the seafront boardwalk, no matter the weather. These walks were how the people in town knew him, if they knew him at all.

My mother and I took an interest in Jeronimo and his strange life. He claimed, my mother recalled, that he had moved to Ste-Anne to follow a woman, who later spurned him; he said he had been betrayed by friends and other artists alike in Germany, Spain, and the Eastern Townships, southeast of Montréal. He was afflicted, bitter, seemingly uncurious. When we invited Jeronimo that summer to our annual campfire on the beach, I asked him where in the world he would like to travel if he could. “Nowhere!” he replied: the TV was good enough for him.

I would sometimes hear, in the ensuing years, small stories about Jeronimo. My stepgrandfather, for instance, once tried to strike up a conversation with him in English only to receive a terse reply. But mostly, my family thought about Jeronimo only when we visited Ste-Anne and saw him, from the living room window, walking along the boardwalk. We would reminisce about our brief interactions with him but in the end decide not to ring his doorbell.

Mahtani, Sunil. “Arts tourism flourishes in Knowlton area.” Arts and Entertainment Magazine (July 14-21, 1995).

Jeronimo had mostly faded from my thoughts until last spring, when I was living in Chicago and visited a small museum called Intuit . Intuit is a museum of “outsider and intuitive art”—art that is created by those outside of the artistic mainstream, often due to mental or physical disability, race, or other factors. The terms used to describe this kind of art can be fraught. As Andrea K. Scott writes in The New Yorker , “the category of outsider has an inherently lower-rung ring to it.” For this reason, some artists and curators prefer “visionary art,” “art brut,” or “self-taught art.”

But with the term “outsider art,” the museum is “not intending to push [artists] to the outside,” said Deb Kerr, the CEO of Intuit, when I spoke to her in an interview this January. “In fact, we are recognizing that they are not inside this white, male, Eurocentric classical art framework.” Intuit has in its collection work by Joseph Yoakum , a Black veteran who took up art at the age of seventy-one and whose work is currently in a posthumous exhibition at the MoMA, and Henry Darger , a novelist and artist who made monumental works in complete obscurity across decades in his Chicago apartment.

Though the definitional boundaries are hazy, outsider artists are those who work outside of the art world and, sometimes, live as outcasts in society in general. According to Kerr, they create art “as a way to realize their inner vision and to deal with the possible trauma or hardship that they’ve lived through.”

My visit to Intuit inspired me to track down that man I had once known in Québec, whose real name I did not remember. Eventually, using his nickname Jeronimo, I came across a LinkedIn profile—he had listed his profession as “Independent Bone Sculptor”—and a Facebook page with eight friends, a photo showing his face half covered by a skullcap. I considered getting in touch with him, though I had no idea what I would say. Instead, weeks passed, and I searched his real name again to see if I could find some new information.

I did, but it wasn’t what I had hoped. One of the first results on Google was now an obituary published by the only funeral home in Ste-Anne. It used Jeronimo’s—that is, Fritz Kistel’s—passport photo, where his face is streaked by anti-counterfeit markings. He died on March 29, 2021, at seventy-nine years old. He is survived, the obituary reads, by his neighbors and friends.

[Outsider artists] create art “as a way to realize their inner vision and to deal with the possible trauma or hardship that they’ve lived through.”

*

It is difficult to know how to talk about any life once it is completed. Those we know well, or pretend to, like our friends and family, can be inscrutable once they are gone; their living bodies having been replaced by objects, photographs, and ever-graying memories that barely gesture to a whole self. But with Fritz, there is not even that. He had no next of kin and few friends, and his closest companions—those sculptures—are now, according to those in Ste-Anne, unable to be found.

I have struggled with my desire over the last eight months to say something about Fritz’s life when, in the end, maybe there is simply not much to say. It is a tragic realization that much of his life is already lost, that the best I can find to piece it together is an old Facebook page and a few photographs. I feel some sense of duty to tell his story, perhaps, because it feels that otherwise truly everything that he created will be gone.

What has brought me back to Fritz’s story is, more than anything, that despite his ornery nature, his work was imbued with a great wonder. In order to illustrate the world that existed in his head, Fritz even wrote a book—over a hundred pages and dozens of pictures in all—explaining the sociological and geographic features of that world. The sculptures were a peek into a mind that saw his world with a logic of folklore, the rhythm of myth. He would not be satisfied with only creating creatures, but instead needed to be able to imagine their entire universe—the ingredient lists of the shamans’ potions or the exact size of the Mountains of the Mist—in order to retreat there whenever he could.

I searched for more information about Fritz in the months after finding out about his death and discovered a few more details. My mother unearthed an old gallery brochure, which Fritz had given us when we visited his home. I reached out to La Guilde, a gallery in Montréal where Fritz had three exhibitions in the 1990s. I also found, in an online newspaper archive, a letter written by Fritz to the editor of a Montréal newspaper. In the letter, he complains that he sent one of six copies of that handmade book about the Timeless Island to a small museum in Newfoundland, only to have the museum ignore and subsequently misplace his unsolicited delivery.

Through those sources, I discovered that Fritz had studied cabinetmaking as a young man in Germany, which gave him the technical skills necessary for carving. He only started building his creatures around 1988, however, when he lived in the Eastern Townships. It seems that he kept a growing gallery at his rural home, where his sculptures must have intrigued and confused many who came across them. One magazine feature from 1995, ostensibly about a new regional art circuit, instead spends much of its time puzzling over Fritz’s statues of “a four-legged maple syrup producer” and “a ferry fish that ferries people across rivers.”

Asked about visitors’ reactions, Fritz replies in the article, “Some really love it and some just turn around and walk out . . . It depends on your imagination.”

Invitation Card, 1998. C13 D2 651 1998. La Guilde’s Archives, Montréal, Canada.

When he moved to the Gaspé, he kept his own gallery at his home in Ste-Anne but did little to advertise it beyond the sign that drew me there, the one pointing to Jeronimo’s Timeless Island. “The art circle in the Gaspé is very supportive,” my stepfather told me; my stepgrandmother was a painter and had benefited from the peninsula’s tourism. He said, “People are very engaged and into giving other people a chance to expose [their work].” But Fritz—who was cut off by both his lack of French and, perhaps, his disability—kept himself in solitude, never making an effort to ingratiate himself.

Maybe he felt the world had rejected him, and so he rejected the world in turn. In contrast, though, to those romantic stories of self-imposed artistic exile—Baldwin, Hemingway, Stein—there was no audience waiting for Fritz on the other side. He rejected the world; the world, for the most part, did not care. Despite that, he continued to create, to build out his private universe, to occupy that timeless island with more and more life.

“Sometimes, I’m scared of reality,” Fritz told an interviewer from a Montréal newspaper at his gallery exhibition in 1996. “People seem not to be honest. I want to find my own peace.”

*

Over the past two years, so many of us have felt that familiar drive to create, despite living in isolation. But for me, motivation has felt so easily sapped in the pandemic, and what I do write seems more and more distant from the world. The compulsion to create has seemed futile, the art itself more likely to fall flat. When writing about Fritz—or, rather, trying mostly in vain to write about Fritz—I have circled around my memories of him like a snake through grass. I write something, leave it, write something else; I write about anything other than what I mean to write.

Perhaps what has drawn me to Fritz, in addition to the unique strangeness of his work, is my awe at his ability to make beautiful things without those external levers that motivate many of us to creativity: dreams of fame, admiration from strangers, praise from the editor or curator. I do not mean to romanticize his failure to achieve those things or assign some idea of purity to his creations, which feels condescending. In my memory, Fritz was unambiguous about his desire for success—gallery shows or visitors purchasing his work. But even so, he must have known that his art was bound to be forgotten, especially considering he made no plans, as I know, to preserve it after his death.

He continued to create, to build out his private universe, to occupy that timeless island with more and more life. What did he think, notching the final hole in a piece of wood he had collected on one of his walks, before placing the completed piece next to hundreds of others that he must have known would never be sold, would perhaps never even be seen by another? Why did he keep going?

Fritz was an exile from the world, and his work, too, resisted the expectations of art. There is not an easy line between the self-imposed nature of his exile (his choice to work in a place where he did not know the language, as well as his general disengagement from the community) and those parts that were placed on him from the outside, such as his disability and the confusion his art seemed to generate in some observers. Nonetheless, I believe that Fritz, as Deb Kerr from Intuit told me about outsider artists in general, made his art to interpret a world from which he felt estranged. Though his status as an exile came from several directions, it culminated in work that gave him some peace and meaning.

He never bowed to the artist’s necessity to sell themselves to gain visibility; he created for creation’s sake, for himself, outside of our capitalist expectations of how art should be used. In a 1996 review of his gallery show, in the English-language Montréal Gazette , a writer called Henry Lehmann hits on this aspect of his work: “[Fritz] Kistel’s spiky mergers of human and monster,” Lehmann writes, “look especially unemployable in our post-industrial, corporate society.” The world of the Timeless Island can be, then, a critique of the society from which Fritz decided to withdraw, a fabulously unproductive body of work in the capitalist sense, but one that nonetheless held great personal significance.

Mahtani, Sunil. “Arts tourism flourishes in Knowlton area.” Arts and Entertainment Magazine (July 14-21, 1995).

*

My family and I avoided Fritz in the years after our initial meeting. “I felt like I didn’t know what else we had to say to each other,” my mother told me. It was unpleasant to face his bitterness at the world, to feel that he was living a life of regret. It was unpleasant, too, to face his studio full of carvings that—despite the book of prices at the entrance—never moved. My stepfather told me, “I don’t remember [him having] a single happy or positive outtake on his situation or the human condition.”

But in his creative life, Fritz’s work continues to inspire me—to create, for myself, even with the knowledge that it may well affect nothing. Where his creatures live, there is no violence, Fritz was careful to write in his gallery brochure. The world works in unison. In each of the eight zones, there are rituals and celebrations. The seasons come and go. Every creature has a purpose, every creature a name, and everyone rejoices in each new arrival.

“After a sculpture is finished,” Fritz writes in the notes for his 1996 gallery exhibition, “the now-alive being retreats to ‘the Timeless Island’ and roams the area for which it was fated. It will appear at every given opportunity to fulfill its destiny.”

A reclusive artist, making work that is unregarded and unsold, hostile to society’s demands, will never have a legitimate role in our world. On the Timeless Island, perhaps, there was more space for Fritz to fulfill that destiny, which he could never seem to escape.

Fritz on the beach, 2012. Photograph courtesy of the author.