Columns Grief at a Distance

How to Date While You’re Grieving

The point of dating is to get to know another person. It’s a process made more confusing when, in my grief, I’m getting reacquainted with myself.

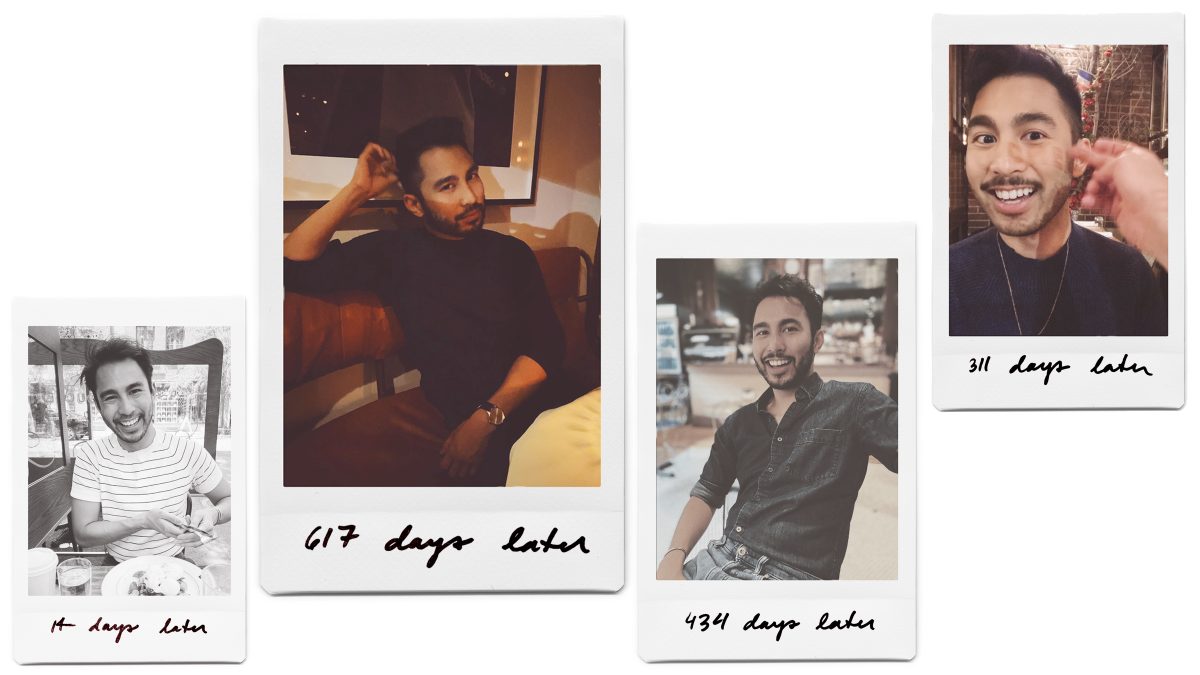

This is Grief at a Distance , a column by Matt Ortile examining his grief over his mother’s death in the Philippines during the Covid-19 pandemic.

On our first date, I told Colm that my mother was dying.

Technically, it was our third. We’d already “had drinks” over FaceTime twice before. Even over bad Wi-Fi, I could see his eyes twinkled like stars. He thought I was handsome too; thanks, I said, it’s the beard. We talked about where we’d gone to school, how we liked working from home, what we did to keep fit in isolation. (Him, biking; me, nothing.) For our first in-person date, he invited me to go on “a fun walk.” By then, it was late May 2020. New daily Covid cases in New York were in the seven hundreds. Mom’s condition had begun to deteriorate. Life’s short. I said yes.

It was sunny when Colm rolled up to Butter & Scotch with his bike, a sheen of sweat on his brow. We grabbed iced coffees, found an empty bench, and sat a foot apart. I asked about his family, very New England. He asked about mine, very far away. I visit Manila every year, I said, but with the pandemic, who knows? The last time I was there was Christmas and—at this, I paused. I’d been careful with my words all day, more so than usual. Historically, I’m effusive on dates; sparkling , I’ve been told, or too much of an open book. With Colm, I worried I was coming off reserved, even taciturn. I didn’t want to overwhelm him with my anticipatory grief, my baggage yet to arrive. But it felt like denial to not mention Mom, she who took up my whole heart while I hoped to make room for him.

So I told Colm: My mom has cancer, it’s not looking good, and I likely won’t be with her when she dies. I don’t remember what he said, only that he retained his composure and showed no signs of bolting. We finished our coffees, I asked him out again, and he said yes. On our dates, he earnestly engaged me and my grief. He once asked about kids: What would parenthood mean to you? I cried in front of him and my ring light and apologized for revealing too much too soon. Don’t be sorry, he said. He embraced my vulnerability, wished he could embrace me through the phone. When I went to bed, I thought about what my family could look like in the future. Who wouldn’t be there? Who could fit into it?

Soon enough, I woke up to fifty missed calls from my stepfather. I spent the day breaking the news to my people. Everyone said some version of I’m sorry , as in I’m sorry for your loss . Colm did not. He did send me a voice clip of him reading a poem by E. E. Cummings: “Now the ears of my ears awake,” he said. “And now the eyes of my eyes are opened.”

Too soon, Colm sat me down to talk. He didn’t “feel the spark.” I wasn’t totally surprised. I had an inkling that I wrote off as paranoia. The evidence, at least, didn’t prove his disinterest: The day after Mom died, we kissed for the first time; he was ravenous and respectful, untangled himself from me before we missed our dinner reservation. His texts were clear and consistent, maintained over long weekends away. He habitually checked in with me, asked how my grief sat in my heart as I learned the weight of it. A typical Colm text: have you breathed today?

Breathing was low on my list at the time. I wanted business, distractions. I persisted with the virtual tour for my book, which debuted the week before Mom’s death. (My publicist triple-checked if I was sure when I said “let’s not cancel any events.”) At work for this magazine, I took bereavement leave for only five days. I could have stayed off-line for longer, but I feared being alone with my grief; thoughts of Mom, of “joining her,” would flicker in the night. Awfully committed to “honoring her” in my work—through labor itself—I refused to take a breath and risked burning out.

Colm slowed me down and tethered me to earth. He fed me, held my hand, took me to his roof and showed me, even in darkness, how bright stars could be. I relished my nights with him, sometimes in disbelief—how low were my lows, and high my highs. For example: Colm once lit tapered candles and set the table with cloth napkins. As he made dinner, he asked how I was doing, how’s the grief today? I’d accidentally shaved off my beard, I said, because I was unfocused, thinking about Mom. I was insecure about my clean-shaven face and asked him what he thought. Colm came over to me at the kitchen island, put his hand on the back of my head, and pulled me in for a deep kiss. He said, “You look good,” and he tasted like oranges.

Maybe I misread the signs. Maybe I’d mistaken ordinary kindness for deep attraction, love, a spark. Grief is harrowing enough, I have heard, in a time without a pandemic. To lose a parent in a year of literal isolation, of masks and gloves and shields, of terrible distance—from my family abroad and my friends five blocks away—was to endure and delight in and suffer at a dilated intensity that skewed my perception of the world. That is to say: Maybe I misread the signs. Maybe I’d mistaken Colm’s ordinary kindness for deep attraction, love, a spark. My mother was dying, and I couldn’t (didn’t) fly to her side. The regret, guilt, and bitterness were (are?) difficult to dispel. In this distorted state, it felt all the more luminous to meet and know and touch Colm; to close the space between us, this man who seemed to care for me; to once again taste sweetness.

But he was right about the spark, in a sense. Something dimmed inside me as time wore on, as whatever we had faded, as losing Mom felt more real. Honestly, I told Colm, yes, I no longer feel a spark either. I just didn’t know if that was a matter of our chemistry, my grief, or both. There was no use in arguing, I conceded, and we said our goodbyes. After that, I avoided oranges for a month.

*

Whenever I had the energy to go on dates in that first year of my bereavement, I always mentioned Mom’s death. It was never hard to say. I was always thinking about her. I talked about her at work, on Twitter, during my book tour. Why not with good-looking strangers over cocktails? Some were kind, said I’m sorry . Others didn’t have the right words, or even words at all. The spark wasn’t always there. Many were scared off. None, save for one, stuck around beyond a week.

Certain social mores would have decreed that I not open up so soon after a loss—at least not in a romantic context. I came of age when the popular dating dictum was to “be chill,” as in to play it cool, to not be so “intense” ( chill ’s Urban Dictionary antonym), to conceal my unvarnished emotions or desire. I’ve long resisted this ordinance (if I like you, I will tell you!), but in the context of bereavement, I admit there’s a logic to restraint. The point of dating is to get to know another person, to see if someone’s life fits with mine. It’s a process made more confusing when, in my grief, I’m getting reacquainted with myself.

Whenever I mentioned Mom, I intended it as a disclaimer. The phrase “my mother is dying”—and, afterward, “my mother just died”—was my shorthand for an abundance of anxieties: I’m feeling overwhelmed. I’m sorry if I’m coming across as dead inside. If I cry suddenly at dinner, please know that it’s not totally without reason. Of course, it wasn’t mandatory that I disclose my loss over something as casual as beers or tapas. But at the time, I think, my guilt over not being with Mom when she died had yet to fade. Ever the lapsed Catholic, my first impulse was to confess, to seek absolution from something painful. So I never learned to hide my grief. I never bothered. I knew early on that it never goes away, that to live well after loss means adapting to it, making space for it in my life . But refusing to suffocate my grief means giving it oxygen. I wasn’t sure how much breath I could spare for a boy. On first dates, I wanted to say: Are you up for this?

Colm was, for a while. We freely talked about Mom, even if doing so at times felt stilted. We often spoke about my bereavement in the millennial vernacular of therapyspeak, as in: Thank you, Matt, for holding space with me tonight as you grieve. It felt cautious, like grocery shopping with disposable gloves, breathing through a face mask. Perhaps if we had been more mature— we being our relationship and, I suppose, ourselves—we could have parsed my grief more effortlessly, with fewer filters. Such an unconstrained language between lovers requires a deep familiarity we didn’t yet have. Still, that we could at all discuss something as heavy as loss was a gift. But after Colm and I parted ways, most of my dates were not as game to do so.

Fine , I would think, dispirited, ghosted yet again. Let this be my litmus test. Let my grief weed out the weak. I was facing this scary thing. I wanted someone to be brave with me.

Certain social mores would have decreed that I not open up so soon after a loss—at least not in a romantic context. Now, I realize, I can’t blame them. I acknowledge it can be uncomfortable or challenging to talk about loss, whether you’re the bereaved or their friend. I’ve been privileged with beloveds (and licensed therapists) who let me grieve my mother with them, who welcome my candor and trust. For those without such networks of support, it can be daunting to discuss grief when people around them may not understand—or even want to understand—what they’re going through. Conversely, the trauma of losing a loved one can be so intense that the bereaved might cut themselves off from the very people who want to help. We risk getting trapped in the depression cave, as my friends and I call it, when we feel the cave collapsing and, overwhelmed, forget to reach out.

Almost two years after losing Mom, I have a better sense now of what I needed most in those early days of my bereavement: the assurance that someone I’m dating could walk with me as I embark on the lifelong project of carrying my grief. My chosen family and friends have accompanied me on this journey, as I expected. I was less sure that potential partners were up to the task. But the more I’ve integrated my grief into my life, as it’s moved into a more constant but sober state, I’ve come to see my grief as not something I need to confess or to be saved from, nor a burden that I foist onto others. Among the bereaved, there’s a popular quotation passed around that’s meant to counsel and comfort: “Bereavement is a universal and integral part of our experience of love,” C. S. Lewis writes in his short book A Grief Observed , in which he mourns his late wife. “It is not the truncation of the process, but one of its phases; not the interruption of the dance, but the next figure.”

I like to believe that formula. Right after Mom died, I saw my acute grief as this massive boulder in my heart. It felt like the love I had for her was pushed out; only sadness and longing was left. But as weeks, months, a year and more passed, I came to understand that this immovable thing is that same love, only changed. To lose Mom was to lose a direct outlet for my love for her. So I try to exhibit love in the ways most familiar to me. I pick up my pen, yes, and write too many words. I tell stories about my mother, memories and jokes; I address them to her too, to the ether, confident that she’s somewhere, listening. I seek connection, leaning on my people, both old and new. And, whenever I can breathe, I go on dates, unabashed and unchill. There are risks to this, I know. But better to have loved and lost.

To talk about grief is to talk about love. I open up to my dates about Mom for the same reason I share my coming-out story, my ambitions, or the books I adore most in this world: to shed light on what shapes me, animates me, has become an intractable part of who I am. To love me, I fear, is to also live with this loss. Just as I am continually learning how it shapes me, we can try to see together, if you like, how it might affect our relationship, what I will need from you—and you me. My habitual disclosure of grief has been a test, a warning, an acknowledgement of why I’m not sparkling—sometimes all of these things at once. Now, I mean it as an invitation: Would you like to walk together?

It won’t always be a fun walk, to be sure, and the walk may end too soon. In that first year after Mom died, the one who stuck around was a man I’ll call Ben. He wanted to walk with me—to run, let’s say. Right around Mom’s first death anniversary, I told him I couldn’t. But Ben and I remain friends. A few months after we became just that, we met up in the West Village and caught up over drinks. We still wanted to get to know each other.

As a gag, we asked each other questions from the Inside the Actors Studio questionnaire . Ben posed to me, “If heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the pearly gates?” The answer came to me easily: She’s waiting for you.

Without words, Ben hugged me. How wonderful it was, to be embraced, even when I didn’t feel the spark.