Catapult Alumni Nonfiction

Caution! Hypersensitive Bipolar Lady Wearing Earplugs

This memoir excerpt was written by Marisa Russello in Megan Stielstra’s 12-Month Memoir Generator

Marisa Russello and her husband were trapped on a flight at 36,000 feet when she had a mental breakdown. They’d hoped for an escape from her depression and anxiety; instead, stress and lack of sleep triggered her descent into a mixed state with psychosis. A mixed state, considered the most dangerous type of bipolar episode, is when someone experiences mania and depression at the same time. For her, that meant moods fluctuating between extremes of euphoria, fits of rage, and outbursts of despair.

Everything You Can ’t Control is the memoir of how a mixed episode derailed Marisa’s life and relationships, and how—by reevaluating her beliefs and examining the choices she’d made — she fought her way back to reality and self-acceptance. The book grapples with questions of identity: How we see and treat others; how we see and treat ourselves.

The following excerpt is from the memoir.

*

Alert for the arrival of my transport, I stood leaning against the door to my cell with the palms of my hands pressed against the glass. It wasn’t long before there was a flashing red light at the entrance to indicate the presence of someone in the vestibule. Soon after, a security guard entered the unit, along with a staff member dressed in blue scrubs pushing an empty wheelchair. As they spoke to a nurse, I opened my door and grabbed the paper bag of my personal items: my journal, a box of ten Crayola markers, an extra set of earplugs (besides the pair I wore), my mango-flavored chapstick, my migraine aromatherapy stick, and a lime Jell-O.

“Can I see your wristband?” the security guard asked when they got to my room. I held out my arm, so he could verify my name. “We’re here to transport you to Nine Garden North. My name is Amadou, and this is Carmen. You can take a seat.” He gestured toward the wheelchair.

I cringed. “I’d rather walk.”

“Sorry, you need to sit.”

I reluctantly sank into the chair and placed my sock-covered feet on the footrests.

As we passed through the tiny vestibule, I felt relieved to be escaping. The tune of The Jefferson’s theme song materialized in my mind, and I instantly thought of new lyrics: “I’m movin’ on up, on the West side, to a deluxe psych ward on the ninth floor.” Luckily, I was able to contain myself and only repeated the melody in my head.

I got through a few verses before being bombarded with jarring noise and commotion. Crossing through the general ER was a cacophony of blaring beeps, waves of voices, and heavy machinery. Even with earplugs, I had to press my hands against my ears and squeeze the paper bag between my thighs so it wouldn’t fall. I shut my eyes in an attempt to drown out the activity.

Once we were out of the red zone, I grabbed the bag again. “How long is this trip?”

“About ten minutes,” the security guard said.

Ten minutes? There was too much stimulation and I felt like we were breaking some sort of hospital speed limit. “It takes ten minutes to travel somewhere in the same building?” I asked.

“It’s a big hospital,” Carmen said.

We whizzed by giant pieces of medical machinery lying abandoned along the hallway. I wondered what all the equipment did and why this space was deserted. I asked Carmen and the security guard, whose name I couldn’t recall, about the different machines and where everyone was, but they didn’t know either.

We passed through another set of double doors and a sign that read, “Nephrology.” The term sounded vaguely familiar to me. The word “nephron” popped into my brain from biology class years ago, and I realized that unit must have something to do with kidneys. Striding through the hall, doctors and nurses with determined expressions carried thick folders and clipboards. “Are you performing a kidney transplant today?” I called out to some people passing by. But no one responded. They didn’t even look down.

“Why aren’t they answering me?” I asked, frowning.

“Everyone is very busy at the hospital,” the security guard said.

Through the next round of doors was an atrium of elevators and newly polished tile floors that caused the chair wheels to spin faster and screech until we came to an abrupt halt. Several people were waiting in front of the doors. All at once I felt anxious and naked in my paper scrubs. Could these other people tell where I was going? What kind of patient I was? I sighed when they all got off before we reached the ninth floor.

After leaving the elevator, Carmen announced we’d be going over a bridge. I didn’t know what to expect, but it ended up being the highlight of my trip. Rolling onto the overpass, I was overcome by the sudden brightness and vibrancy around me. My blood seemed to run faster through my veins. The thinly carpeted floor made for a smooth ride, and aside from my companions’ muted, rhythmic footsteps, the passageway was silent. Both sides were transparent, allowing me to view the powder blue sky and the bustling, city street below. Just a few wispy clouds were littered across the horizon while sunlight illuminated everything on the ground. Some people without jackets tightly crossed their arms while others brushed hair out of their faces. There must have been a light breeze. I could see a small garden blossoming yellow in the distance. I missed the smell of flowers, of the outdoors. I considered the stagnant hospital air with its astringent scent; it felt progressively more synthetic as we neared the end of the tunnel.

I took my last gaze down at the scurry of Manhattan with its mobs of pedestrians forging ahead, each on their own personal mission without regard for anyone else. I envied their freedom. After all, I was being transported from one prison to a slightly more accommodating one.

Upon entering Nine Garden North, my mind was overcome by sound, and my nostrils were assaulted by the stench of cafeteria food compressed into the small space. I winced. Silverware was clinking and clanking against dishes like I’d just walked into a metal factory. The odor of heavily marinated barbecue chicken sent my stomach into a lurch. I rocked back and forth in the wheelchair and rubbed my wrists with my fingers. My muscles twitched. People were banging their glasses against tabletops and erupting into laughter as if trying to provoke me.

They kept yapping and shoving chicken in their mouths while I sat alone and disoriented in this new place. But I didn’t have the luxury of processing my feelings about where I was going or what these people thought of me. In that moment my skin flushed with heat, and a sense of nausea overwhelmed my body. My heart sat in my throat. Voices rebounded against the walls of the enclosed room, and I impulsively pressed my fingers into my ears. It did nothing. My head throbbed, pulsating at my temples and behind my eyes, as I tried to shut out their piercing laughs and the urge to vomit.

I hardly noticed what was happening when Carmen helped me out of the wheelchair and left me standing across from a pregnant brunette with a big smile. Her lips moved, and her eyes flitted to the ID badge around my wrist.

“You need to speak louder. I have ear plugs in.” I turned my head to the side and pointed to the bright yellow foam. I wish I were wearing a sign, I thought: Caution! Hypersensitive Bipolar Lady Wearing Earplugs: Speak Up . . . But Not Too Much.

“Hi, I’m Elena. I’ll be your nurse today,” she said audibly then. She held out her hand.

“I’m Marisa,” I said. “Sorry, I can’t shake hands right now.” Damn, I needed a sign for that too. How many more people did I have to meet here?

“Okay, that’s fine.” Her arm fell back to her side. “And why do you have earplugs in?” She asked this without any noticeable irritation or judgment. Already a big difference from the ER.

“I’m in a mixed episode, so I’m very sensitive to everything right now.”

Elena didn’t falter. “I’m sorry to hear that. Would you like to have lunch now?”

My attention was drawn back to the sounds and smells of the dining room. The silverware clashing. The bursts of laughter. The scent of steamed broccoli and Cool Ranch Doritos mingling in still air. I needed to get out of this place. Now. “No!” I blurted out.

She raised her eyebrows.

Calm down, I told myself. Deep breaths. “Thanks, but my family will bring me a sandwich during visiting hours.”

“Let’s go for a walk,” she said. “I’ll give you a tour of the unit.”

I nodded, wondering if my agitation was palpable. I followed her several feet down the hall before she paused.

“The large room where everyone is eating is the dining room. Right behind it is the activity room. Art therapy takes place there.” Elena guided me further into the unit, which wasn’t big. She showed me the nurses’ station where I would get my meds, the large white board where the schedule was written each morning, and the day room. It had several rows of brown faux leather sofa chairs lined up in front of a wide screen television.

When we got to my bedroom, the first thing I noticed was the giant red button protruding from the wall outside my bathroom. I pointed. “What’s that?”

“Don’t push it,” Elena said.

“The only reason they make big red buttons is for them to be pushed!”

“Not this one.”

“What’s it for?”

“Extreme emergencies.” Her tone was serious.

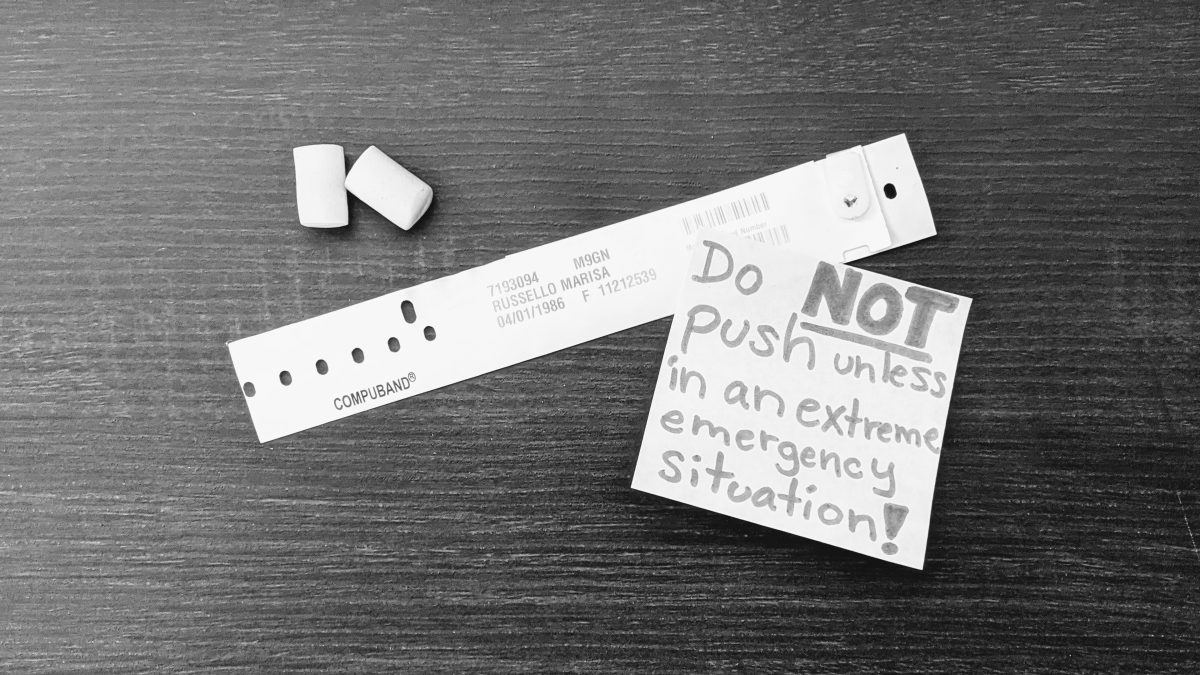

I grabbed one of the post-it notes I’d stuck in the back of my journal along with a red marker and wrote in all capital letters: “DO NOT PUSH UNLESS IN AN EXTREME EMERGENCY SITUATION!” I carefully positioned the post-it above the button.

“Is that really necessary?” Elena asked with an almost smirk.

I looked at her and back at the button, beckoning me. The button was calling out “Push me!” like that piece of cake tempted Alice in Wonderland with its “Eat me” sign.

“Yes,” I said. “I really want to press that button, but the post-it will stop me.”

Elena seemed doubtful. “I hope so.”

I hope so too , I thought.