Arts & Culture Rekindle

Mavis Gallant and Me; or, Where Are You From?

Like her, I was a Canadian who left Canada. Like her, I wanted to be an unsentimental writer. But I was not Mavis Gallant.

The first time I thought I was leaving my hometown for good, I was eighteen and off to university. I entertained sentimental hopes about becoming an unsentimental writer.

The first time I read Mavis Gallant, whose Collected Stories was reissued this month, I was in high school. I loved her short stories because so many of them took place abroad. They were foreign to me.

I had always felt foreign in Winnipeg, Canada, the place I’d lived for most of my life. But I ended up coming back to Winnipeg, to my parents’ home, to my friends, over and over. I came back to Mavis Gallant’s stories, too. Each time I read them, they changed. Or perhaps I did.

*

Mavis Gallant, who died on February 18, 2014, at age ninety-one, began her career as a journalist for the Montreal Standard in 1944. At a time when women were rare in the newsroom, she had her own column. She broke a story about international baby traffickers who (conveniently—for them) ran a home for unwed mothers. But Gallant’s time at the Standard was fraught. In a semi-autobiographical short story—one of a series about a young woman named Linnet Muir—Linnet overhears a male editor say, “If it hadn’t been for the god-damned war we would never have hired even one of the god-damned women.”

In the early 1950s, Gallant moved to Europe to write fiction. In 1951, she had her first short story published in The New Yorker . She soon sold more stories, which her agent told her had been rejected—in reality, he had pocketed the funds, even though he knew Gallant was (in her own words) “terribly hard up.” Fortunately, editor William Shawn managed to locate her and send her money before she had to pawn all of her clothing.

By the time of her death, Gallant had written 116 stories for The New Yorker and contributed reportage on the 1968 student uprisings in Paris. She had also penned two novels, a play, and several essays. She wrote about ex-pats and displaced people who’d never really belonged in their home countries. She wrote about the postwar period. She wrote about sheltered French girls and hapless publishers. She wrote with crystal clarity about a Montreal of long ago:

The rest of their things were carried by two small, bent men to the second floor of a stone house in Rue Cherrier near the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. The men used an old horse and an open cart of the removal. They told Mme. Carette that they had never worked outside that quarter; they knew only some forty streets in Montreal but knew them thoroughly. On moving day, soft snow, like greying lace, fell.

She married and divorced once in her youth. In an interview, she said that she’d tried living with someone once, but that it interfered with her writing.

* In 2006, radio station WNYC’s Selected Shorts planned a tribute to Gallant at Symphony Space, featuring Russell Banks, Michael Ondaatje, and Jhumpa Lahiri reading her work. Gallant was to attend, though she was in her eighties and hobbled by osteoporosis.

I told my then-boyfriend, now-husband B that I wanted to see her. I had met B, in part, because he mentioned that he liked Mavis Gallant in his dating website profile. When I told B about the program, he grumbled that he didn’t understand the point of watching a bunch of writers read aloud. I told him that I found a great deal of personal significance in Mavis Gallant and wanted to see her. I quietly ordered two seats for the event, deciding I’d take a friend.

A couple of weeks before the reading, he told me he had a surprise for me. Of course, he produced a pair of tickets. He had planned it all along. It was the best gift I’ve ever received, though the mix-up wasn’t worthy of an O. Henry story. We kept one pair of tickets and hawked the other.

*

Some critics complained that Gallant’s writing was cold. Those that praised the diamond-sharp beauty of her prose also said that it suffered from emotional detachment, as if they suspected she’d struck a bargain with a white-eyed demon in order to achieve such perfection. Gallant once described a character in “Bonaventure” as a vivisectionist, and vivisection is perhaps an apt representation of her writing—maybe it was her unflinching eye, her steady hand as she made each cut that made critics queasy. But as skilled as she was at peeling back the skin of a live being, she was also careful to record the pumping of the organs within.

“Mlle. Dias de Corta,” a story about a conservative, elderly French woman, takes the form of a letter to the eponymous long-ago former boarder. It is gradually revealed that, years ago, Alma Dias de Corta was impregnated by the narrator’s son. She came to the woman for advice on how to get an abortion, was rebuffed, then disappeared.

The story is a character study that exposes the prejudices and pettiness of the very French narrator. She describes her daughter-in-law as a woman of “mixed descent” because “[t]wo of her grandparents are Swiss.” But the story also shows us her regret at not having supported her vanished boarder. The result is a portrait of a flawed person haltingly reconsidering her misplaced loyalties late in life. In the last lines of the letter, she writes to Alma with sudden, aching clarity:

You need not call or make an appointment. I prefer to live in the expectation of hearing the elevator stop at my floor and then your ring, and of telling me you have come home.

*

Gallant identified as Canadian, although she lived in Paris for upward of sixty years. She never changed her citizenship. She had endured a peripatetic childhood, which included stints in seventeen boarding schools across the United States and Canada. Her English father died when she was young, and her American mother did not have the inclination to raise a child.

At the event I attended with my husband, her reading voice was vaguely transatlantic with its gentle Rs and flat vowels—a voice from another time. She was a small— a nugget, B called her—sitting in an enormous wing chair, reading one of her stories about Parisian publisher Henri Griffes.

She disdained analysis of her work. In conversation with Jhumpa Lahiri a few years later, she resisted the younger writer’s attempt to dissect her stories. I have a feeling she would dislike being cast as a French spinster witch who embraces her solitude. She didn’t like being categorized as someone who wrote about expats and exiles. And maybe this is correct—many of her stories are about people with strong roots in France, or Montreal. These characters are settled in their homes and their ways. And the displacement of their characters is not always about place; sometimes, it is about time.

*

I was not looking for iterations of myself when I started reading Mavis Gallant. Correction: I should not have been looking for myself. As a person of Taiwanese descent growing up in a mostly white neighborhood in Winnipeg in the eighties and early nineties, I was regularly asked where I was from, even though I was Canadian-born. When I told people where my parents grew up—well, they didn’t know where that was, either. Not that Taiwan is recognized as a real country by the United Nations, anyway. Not that the people asking really cared.

I read Gallant’s stories because they were beautiful and because I was apart from them—because the characters were, like me, apart from themselves. I read Gallant’s stories as a young person, but it is over time that I have grown to love her. I tried to write short stories, like her, but it was hard. I tried for a while to be alone—but that was hard, too. It was boneheaded of me to try to emulate her, as a person of my own time period and of my own background.

If I learned anything from Gallant’s writing, it was to pay attention to the character, to the unique circumstance that made each story its own. In many ways, she taught me how to observe—and maybe that helped me see myself, too.

Now, I think the only thing Gallant and I have in common is that we have been Canadians who’ve lived outside of Canada for most of our adult lives. And for both of us, the idea of going back is unattainable.

*

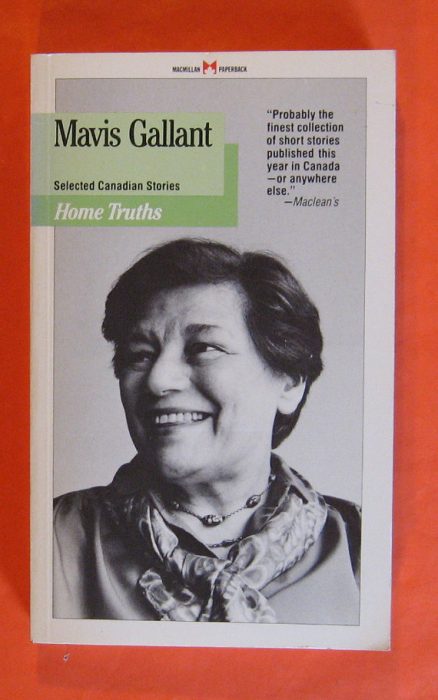

Recently I bought a Kindle copy of Home Truths: Selected Canadian Stories . Somewhere in my past I owned a paperback version, but I have no idea where it is. I remember the cover was a black-and-white picture of the author, smiling at something off camera. She wore a scarf, tout comme il faut. Near the bottom, a green strip bore the name of the book. My parents left my hometown—their home for more than thirty years—for British Columbia in 2009, and they haven’t been able to find the book among the boxes of my things.

I will likely never move back to Canada, even though that’s what everyone talks about doing in this election year. Marrying an American, and having a kid, cemented my decision to stay in the U.S. Aside from that, I don’t have anywhere in Canada I could easily return to. I was born in Vancouver, where my parents now live, but I never spent any significant amount of time there. I grew up in Winnipeg, but most of my friends have left that city, too. I’ve lost my accent. I’ve forgotten my French-immersion Franglais.

In the United States, I often reach for my Canadian identity—it’s easier to spout punchlines about being Canadian than it is to explain my Taiwanese heritage. It’s easier to let people place me. It’s easier to place myself. People still ask me where I’m from. I’m too old and tired to embark on earnest explanations for those who only seek pat answers about my skin and the shape of my eyes.

The Canadian part of my identity is based on vapor and snow. I never knew Taiwan. I would not know Winnipeg if I went back. I don’t know Canada anymore. I am still frequently bewildered by the loss—not only because what I remember is no longer there the same way, but because that loss has seemingly not changed who I am.

Before I caved and bought the Kindle copy, I tried to find a paperback—my paperback—of Home Truths through Amazon Canada. There it was, in black, white, and green. I added it to my cart. But the store recognized that I wasn’t in Canada—it detected my alien IP address—and the book became unavailable.