People Fans

Their Songs: The Ballad of Elton John and Bernie Taupin

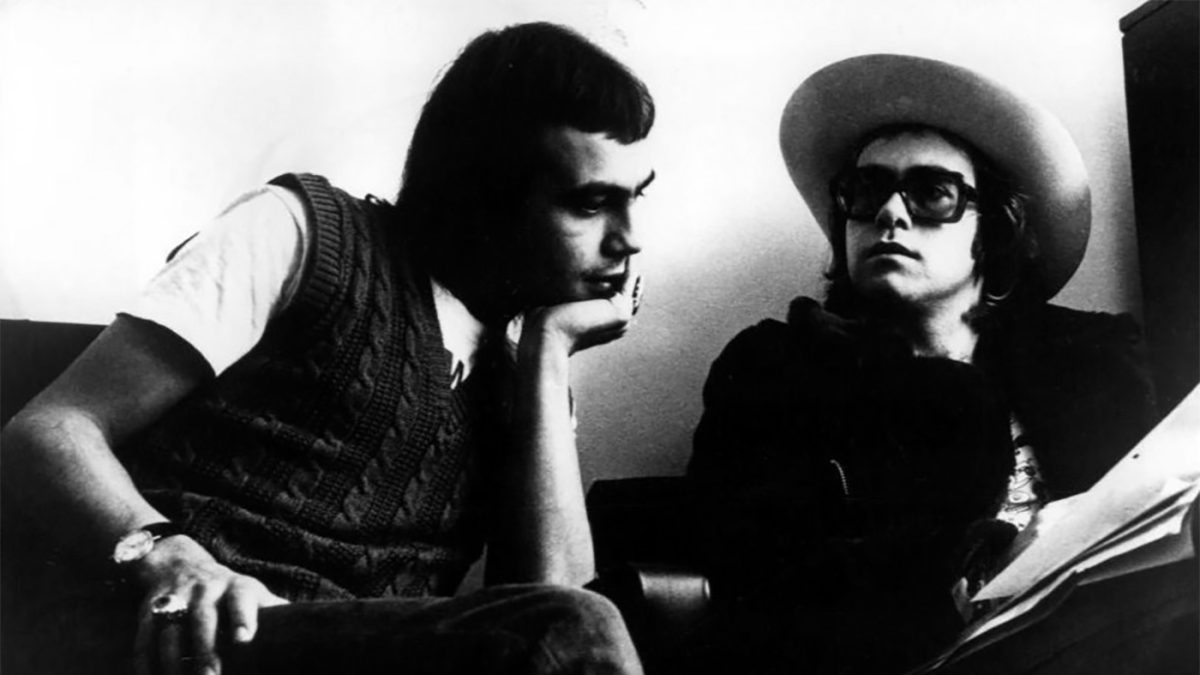

Elton John and lyricist Bernie Taupin collaborated to create timeless pop songs during the 1970s.

Walking down St. Mark’s Place recently, a car drove past blasting Elton John’s 1974 single “Bennie and the Jets.” Stopping at the red light, the middle-aged driver sang loudly and pretended that the steering wheel was a piano as I wondered if my used-to-be-favorite singer was dead. Back in April, it was reported that Elton was canceling tour dates because of a “harmful and unusual bacterial infection” he’d caught in South America. With so many of my musical idols—Cynthia Robinson, David Bowie, Prince, George Michael, Maurice White—dying in the last few years, it was possible that seventy-year-old Sir Elton would be the next star strutting through the pearly gates of Pop Star Heaven.

“Not another one,” I sighed, reaching into my jeans pocket to retrieve my phone.

Checking the news reports, I scrolled through the entertainment headlines as my mind drifted back to those 1974 WABC mornings when “Bennie and the Jets” was served daily alongside my sugary cereal or toasted waffles. At eleven years old, I sat in the corner chair in the kitchen dressed in my St. Catherine of Genoa school uniform: white shirt, blue tie, and dark slacks. The radio was a few feet away on an end table in the living room. A dark wooden box with scratches on top, it was a gift from my stepfather, Carlos, who more than likely bought it hot in the barber shop where he cut hair. WABC morning jock Harry Harrison played the Top-40 jams by Chicago, Stevie Wonder, Steely Dan, and countless others that nudged me toward a pop appreciation that later became an obsession.

“BATJ” was first featured on John’s double-disc album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and was released as a single in February 1974. Hearing the song every morning, I began imagining that cool girl named Bennie who wore “electric boots and a mohair suit,” leading her band toward electric music and solid walls of sound. The more I heard “BATJ” on the radio, the more I wanted to be able to play it whenever I felt like it. After pestering Mom for a few days, she finally brought home the seven-inch single, which was the first rock record added to my then-growing vinyl collection. Besides the immediate satisfaction of owning the record, that song also served as a sonic gateway into glam and the blaring music of the makeup-wearing young dudes Kiss, Queen, Alice Cooper, Marc Bolan and David Bowie, that guided me through the seventies.

Though my changing musical tastes would later clash with the soul/disco tunes that friends and family preferred, “BATJ” proved an exception to the “white-boy music” sneers, because it had unexpectedly crossed over to the R&B charts with a little help from then twenty-year-old Detroit disc jockey Donnie Simpson, who spun the track regularly on his nighttime show on WJLM. The addictive groove driven by Elton’s soulful piano tinkling soon became the station’s most requested song as the dramatic opening piano vamp and fake “live” applause became as familiar to Black folks as anything by Al Green, Barry White or Rufus, all who had big hits in ’74. Elton later performed the song on Soul Train, where he played a glass piano and host Don Cornelius described him as having “a kind of psychedelic outlook on life.” Decades later, “BATJ” would be covered by Biz Markie and sampled by Mary J. Blige.

Having nothing to lose, I wanted to be psychedelic too. While my weekly allowance usually went toward buying House of Mystery / House of Secrets comics, I also started purchasing pop teen fan magazines Tiger Beat, 16, Circus, and Hit Parade so I could read more about Elton John. With the exception of buying Right On! a few years before to keep track of the Jackson Five’s latest happenings, I had no idea that there were so many glossy-covered pulp paper journals featuring “autographed” posters, party flicks, press releases masquerading as in-depth interviews, and all the contests you could possibly lose.

In the fan magazine interviews, Elton usually came across as blasé cool, but I thought it was admirable that he always gave his lyricist Bernie Taupin props. Unlike many pop artists that discarded lyricist credits completely or had an egotistical ease for claiming credit for everything, Elton not only talked about Taupin’s talent, but also included him in the album packaging, filmed interviews and occasionally dragged the shy poet on stage to absorb some of the audience’s adoration.

*

Having met in 1967, the two seemingly hit it off immediately and the quaint ditty “Scarecrow” was their first collaboration toward becoming the new Lennon and McCartney or Bacharach and David. However, unlike the musical movie ideal we might have of musical teams and the creative combustion of songwriting together in a solitary room, John and Taupin told interviewers countless times that they worked separately. Theirs was a prolific collaboration, with Elton sometimes releasing two albums a year as well as non-album singles (“Philadelphia Freedom,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”) that also became hits.

“I write the words and he writes the melodies, so there’s no need for us to sit together and do it together,” Taupin told an interviewer/director Bryan Forbes in the 1973 documentary Elton John Bernie Taupin Say Goodbye to Norma Jean and Other Things . Made four years after their first album Empty Sky (1969) was released, I can remember watching when it originally aired in the states on ABC. The fawning narrator described Taupin as a “gentle, unassuming person” and compared his lyrics to the photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson. “[Taupin] writes as he feels when he feels, producing superior lyrics that more often than not are eventually overwhelmed by the mandatory volume of electronic sound.”

By the time that documentary aired, the duo were already known with the singles “Your Song” and “Rocket Man,” but the release of “BATJ,” which Creem magazine critic Wayne Robins dubbed “The Americanization of Elton John,” put them in a different stratosphere of pop stardom. However, when the filmmakers showed a small clip of Bernie headed to his work cottage to write in that room of his own, his quarters, with the exception of the platinum and gold discs lining the wall, was the least rock star environment one has ever seen. Dressed in regular everyman clothes, Bernie sat down behind an electric typewriter, put in a sheet of paper, stuck a pen in his mouth, and briefly stared at the sheet before he began to type.

In those few moments the filmmakers tried to convey that Bernie was a “real writer” who had more in common with an Oxford poet-in-residence than with any stereotypical dirty rockers smoking pot and scribbling words on cocktail napkins. Looking at the doc on YouTube years later, I was struck by Taupin admitting that he thought most pop songs, including his own, were disposable and the only thing one could hope for was creating a standard.

Having been partially raised on my mom’s beloved radio station WNEW-AM, listening to programs that played Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Sarah Vaughn, and big bands , I knew that “standards” were written by oldsters named Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Sammy Cahn, Johnny Burke, and Billy Strayhorn, not Brit boys rocking out. Needless to say, with songs “Tiny Dancer,” “Your Song,” “Rocket Man,” and many others, Taupin and John created timeless songs—standards—that flashed memories and tugged heartstrings when played in movies and television shows and on the car stereo of a passing ride.

Still, not everyone was as enthused with Bernie’s words, with rebel-rousing critic Lester Bangs calling him a horrible lyricist and writing in Phonograph Record magazine, “His lyrics appeal to people who wear their sensitivity . . . on their sleeves,” as though that was a bad thing. Others claimed that Taupin ripped off “Rocket Man” from David Bowie’s sci-fi infatuations, hadn’t tackled politics like Dylan or Curtis Mayfield while having an unhealthy fascination with Americana (cowboys and sock hops) that he romanticized on Tumbleweed Connection (1970) as well as the singles “Honky Cat” and “Crocodile Rock.”

While sensitive Taupin was more than likely stung by the negativity toward his words, he told Beat Instrumental magazine in 1972, “I think that’s a stupid thing to say. If people don’t use their imagination where would we be? People have been writing about things they’ve never seen for years. I think we captured the atmosphere very well.” Taupin found an unlikely ally in critic Robert Christgau who wrote, “. . . although such an analysis is not inaccurate statistically, it’s aesthetically irrelevant.”

*

Within a matter of weeks, “Bennie” was in my blood; my mixed-message bedroom walls were covered with Jet magazine “Beauty of the Week” bikini-wearing centerfolds and glitzy Elton clad in his usually gaudy gear. In the same way Elton seemed to be living vicariously through that wild girl Bennie, who’d he “read about in a magazine,” I began to live vicariously through him. Perhaps, as a wannabe writer, I should have been including Taupin in my hero-worship sessions since he was the wordsmith of the duo, but he seemingly preferred the background, a space I was already familiar with from real life. Why dwell in the shadows if you can be in the spotlight wearing rainbow feathers and diamond-encrusted eyeglasses?

At school, where I was an average sixth grader, I unofficially changed my middle name from “Alan” to “Elton” whenever I signed class papers and homework assignments. I wasn’t the best student or the worst, but one of those in-the-middle kids who was damn near invisible during school hours except for when I got called out for staring into space or gazing out classroom windows. Unlike my then-best friend Raymond Torres, who resembled a Puerto Rican version of James Dean, I never felt as though I fit in and wasn’t always sure I wanted to. Still, changing my name became an act of rebellion as well as a way to be noticed.

“Who is Elton?” Miss Belina, my humorless sixth-grade teacher, asked sarcastically. From the first day of class, she had a habit of looking at me strangely, as though I was special, and the sudden name change seemed to magnify my otherness when compared to my mostly conformist classmates. Meanwhile, our history teacher Mr. Waters, a chubby redhead who was the youngest and coolest of the catholic school lay (non-nun) teachers, humored me with his observation that, “Olivia Newton-John is better.”

Smiling snidely, I knew that Mr. Waters was wrong. We argued the point for a couple of minutes before going back to the lessons. A few weeks later, when I was still signing my work Michael Elton Gonzales, the usually jolly Mr. Waters said grimly, “I’m sure Elton John was promoted from sixth grade, but at the rate you’re going, you’re not going to make it.”

I should’ve been more worried, since I did wind up in summer school, but no matter how much Mom screamed about my grades and “getting my act together,” I simply couldn’t muster the same enthusiasm for math and science that I had for Elton John. Turning twelve at the end of June, I was inspired by an episode of The Brady Bunch when Monkees member Davy Jones went to visit Marcia at home; I invited Elton to my birthday bash and sat outside most of the afternoon waiting for his limo to come gliding down the street.

Although he neither showed up nor called, I forgave him. “Maybe the invite got lost in the mail,” Mom said. “Things like that happen, you know.”

Come Christmas morning 1974, propped against the green, artificial tree with a red bow on the front, was a copy of Elton John Greatest Hits . On the cover, Elton sat in front a black Steinway dressed in an ivory-colored suit, matching hat, and a colorful bowtie. For the remainder of the holiday vacation I played that Elton album every day, relishing in older songs that I didn’t know (“Your Song,” “Rocket Man”) as well as the ones I already knew. It wasn’t enough to simply spin the records and sing along to those sweet, sad songs about rocket men and a dead brother named Daniel, I wanted to be that white-suited man who simply wanted to dance the Crocodile Rock and fight on Saturday nights.

It was my adoration for Elton’s eyeglasses that made me try to fail our annual eye exam so I too could wear spectacles. Eventually, it was also Elton that led me toward music journalism when, in the spring of 1975, I self-published a school newspaper (with the help of Mom and her job’s Xerox machine) simply so I could write a rave review of Elton John’s one scene in the rock opera film Tommy . Based on a concept album by the Who, who wrote and produced the songs, the film starred the group’s singer Roger Daltrey, Ann-Margret, Jack Nicholson, Tina Turner, Eric Clapton, and Elton John as the colossal Doc Marten-wearing opponent wailing the song “Pinball Wizard” while trying to kick Tommy’s ass in the game. Commercials for the film ran for weeks and I was psyched when I noticed the flick would be opening at the Olympia Theater on 107th and Broadway. Tommy opened on a Friday, and twenty-four hours later I was in front of the screen.

Even though I’d anticipated Tommy for months, Elton’s riotous scene battling Tommy for the wizard crown came on over an hour into the film and lasted all of five minutes. Still, that was enough for me to be inspired to spread the written word that he was a giant, both literally (at least in the film) and figuratively. On the subway ride home, as his silver ball scene bounced in my brain, I decided that when I got home I’d pull out my typewriter and write a review about the flick. I wanted my small world to know it existed. Most of my previous writings were horror/science-fiction tales, so this would be something new

Later that afternoon, I set the olive green Olivetti on top of the living room coffee table and placed myself on the couch. Rolling the paper through, I tentatively began typing with my right hand and stumbled through a few sentences before finally tearing the page out and starting again. Taking a break, I pulled out my stash of fan magazines to examine pictures of Elton and study the articles to try to figure out how it was done. After a few more tries at writing the review, I was finally able to churn out a few paragraphs within four hours.

Knowing I couldn’t put out just a one-sheet paper, I wrote a few other short pieces and clipped comics from CARtoons magazine. Afterward, my mom took the pages, retyped the stories, and printed about fifty copies of the paper. The paper itself was five Xeroxed sheets collated and stapled together, which Mom did before giving them to me. The St. Catherine Press was born, or so I thought. That would be the only edition of my short-lived paper since Sister May Riley (“What’s our cut?” she asked) shut it down. Thankfully, it would take more than a couple of mean nuns to discourage me from writing.

*

Two months after Tommy , the singer released his next project Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy . Radio was already playing the newest single “Someone Saved My Life Tonight,” a dramatically sorrowful song about Elton’s fears of being married to now-infamous former fiancée Linda Woodrow. (“Prima Donna lord you really should have been there / Sitting like a princess perched in her electric chair.” ) “That song is about the time he tried to commit suicide,” my mother said casually one morning as the song played on WABC. A few years before, Mom’s friend Thomas had committed suicide; his was the first funeral I’d attended. I knew what suicide meant, and it was difficult for me to think of Elton as being dead.

Bringing the record home the following payday, Mom handed me the album. The wraparound cover featured a mind-boggling image painted by British artist Alan Aldridge and the album was nominated for a Grammy award the following year. In the painting, Elton looked like an eccentric superhero complete with a mask, top hat, and electric boots, while the back cover featured Bernie dressed in a wrinkled vest with a pen in the breast pocket. Elton was surreally posed on a sideways piano with a rose in his hand; Bernie was lying down inside a protective bubble, where he could not be touched by the madness of the world as he wrote in his notebook.

Also included in the fancy packaging was two glossy, full-color booklets titled “Lyrics” and “Scraps,” the latter a scrapbook of handwritten notes, early press clippings, an Elton comic strip reprinted from the Brit fan magazine Jackie , and old photographs including pudgy boyhood pics and another of him posed with Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles, just one of the American soul groups Elton accompanied on piano when they toured England.

Although Bernie told an interviewer in 1973, “I don’t usually sit down and say I want to write a song about this subject or that subject,” that was exactly what happened with the textual creation of Captain Fantastic, an album that served as both autobiography (Taupin) and biography (John).

“It’s a story type album,” Elton told Australian talk show host Molly Meldrum of the chat show Countdown in 1975. “It’s basically about us two and how we met. I’m Captain Fantastic (devilish grin) of course, and he’s the Brown Dirt Cowboy—I put him in his place. It’s just all the experiences we’ve had, the disappointments we had about songs not being used and the people trying to sign you (to contracts) for life. Really, I sincerely, think it’s the best thing we’ve done.”

As though thumbing their noses at the “Americana” critics, the album’s title sounds like the name of a Sam Peckinpah flick. That Wild West vibe came alive on the opening track as a guitar-strumming Davey Johnstone gives us cool country and western foundation while Elton equated travelling with the band to being “on the range.” In both the lyrics and the music, I could hear the real. For the first time, Elton wasn’t singing about various characters but was exploring the encouragement he received from his parents (“Captain Fantastic”), the broken promises of music publishers (“Bitter Fingers”), and finding the right artistic partner (“We All Fall in Love Sometimes”).

The only album track that didn’t, as I found out years later, pertain to their personal lives was “Tower of Babel,” which critic Wayne Robins said was “. . . certainly about the death of Average White Band drummer Robbie McIntosh at a Hollywood party where the revelers snorted a white powder alleged to be ‘Snow/cement,’ but which turned out to be ‘Junk/Angel/This party’s always stacked.’ The anger about that party comes pouring out.” Certainly, since Captain Fantastic was a reflection of rougher times, it was, as Chris Charlesworth wrote in Melody Maker, “a bitter album and one in which Bernie Taupin’s lyrics play a greater role than usual.”

Elsewhere, critic Greg Shaw explained: “. . . It’s hard to say how much Taupin’s lyrics reflect Elton’s feelings (in fact, much of the sourness seems to be Bernie’s), although they must be pretty close in their thinking.” However, while Taupin’s lyrical hostility was aimed at those who tried to get in their way, the record’s most joyful track “Writing” became my chosen special song, the track I played over and over, basking in the morning sunshine (“Waking up to washing up/Making up your bed/Lazy days my razor blade/Could use a better edge” ) that radiated from the song.

Before then, I’d never heard any songs about writing, but even as a young wannabe I could well understand when Elton sang, “Will the things we wrote today, sound as good tomorrow.” While we’ve all heard our share of complaining writers who equate sitting at the keyboard to a meeting with an executor, here was a scribe, through the singing voice of his collaborator, talking about how wonderful it was to struggle to completion. “But don’t disturb us if you hear us trying to instigate the structure of another line or two,” Elton sings before delivering the beautiful final line, “‘Cause writing’s lighting up and I like life enough to see it through.”

Having connected with “Writing” from first listen, over the years it has served as a well-lit motivational anthem that has guided me out of the textual darkness on more than one occasion. Even though most critics agreed that Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt was, up to that point, Elton’s best album, then- Rolling Stone reviewer Jon Landau, who today manages master wordsmith Bruce Springsteen, spent most of his analysis telling us why he thought Taupin sucked as a writer.

“Naturally Taupin’s weaknesses come to the fore on this concept album,” Landau wrote in the July 17, 1975 issue, “but, it’s a strong commentary on his glibness that on a record that is supposed to evoke two people’s personal experiences, there is no sense of particularity. Taupin’s lyrics generate more of the album’s quality of sameness than John’s singing. His clever names and bloated images can’t disguise the lack of original thought.”

Truthfully, I could never understand how one could claim to admire Elton’s seventies songs while hating on the Taupin’s words. It didn’t make sense to me then nor forty-seven years later. Currently, Elton John is preparing an autobiography for Henry Holt Books to be published in 2018, as well as producing the musical biopic Rocketman starring Taron Egerton. I can only hope that those projects capture the bitter beauty, sense of artistic yearning and eventual musical freedom that was captured on Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy .

A year after the release of Captain, much by accident, I discovered the booming blare of Led Zeppelin and the softer AM-radio pop artists I liked were pushed aside for the testosterone wail of Robert Plant and guitarist Jimmy Page. Screeching toward puberty, I desired music that had a sense of sex and danger, and the John/Taupin compositions were just too safe. Preparing myself to be amongst the “big boys” in high school a few months later, Elton John, I thought, was the childish side of me and it was time to listen to the more adult sounds. Still, even in my most heavy metal/prog rock/punk rock/hip-hop days, I occasionally revisited their songs and relished those tales of rocket men, Bennie, and struggling artists as though they were old friends joyfully telling me the same stories again and again.