People Other Selves

The Old Man Who Fought Boko Haram

“Who was this self-appointed vigilante of this street of ours? Why was he so invalid? No one seemed to have a story about him.”

Ask them why they idle there While we suffer, and eat sand. And the crow and the vulture Hover always above our broken fences And strangers walk over our portion. —“Songs of Sorrow,” by Kofi Awoonor

1.

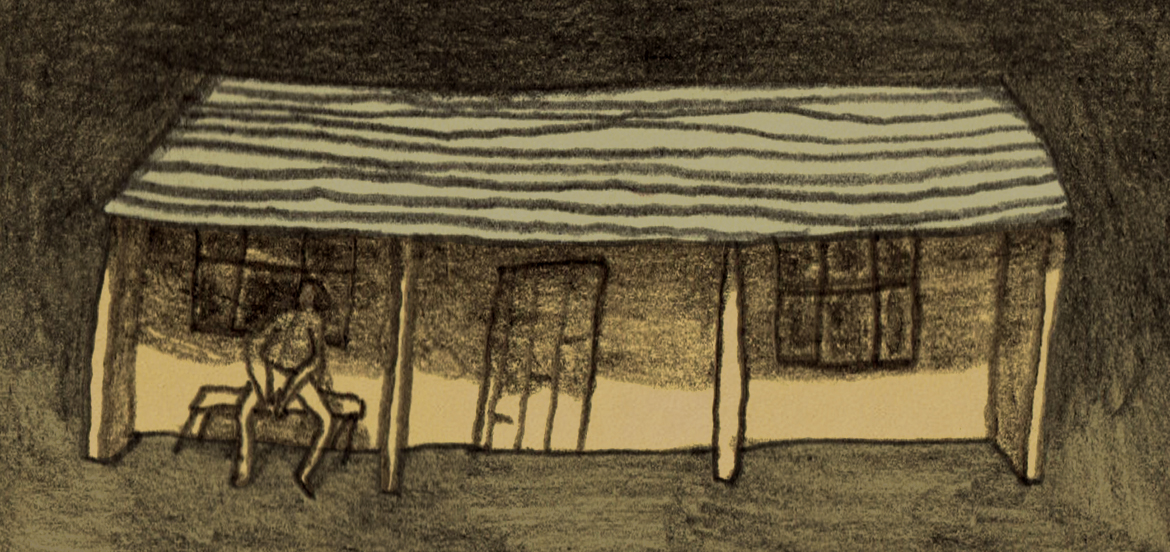

The man who died would sit on the verandah of his small, unfenced and unpainted bungalow, unmoved. Like a stone sculpture, he would sit still and follow everything and every passerby on our street with his eyes. I’d even imagined that he knew who each person was and what time each of us walked by. Whatever illness that took him must have been chipping at him bit by bit for years. He was a sitting collection of bones clothed in flesh with an oblong head and two huge eyeballs peering down at you from their sockets. He must have been sixty-five or seventy years of age or older. He was bald with a scattering of grey facial hair covering his many wrinkles. He reminded me of my maternal grandfather, a man I met only through the stories my mother told me: How stingy he was with words, and would only speak when spoken to, and lived as if in permanent solitude inside his head.

2.

The man died in the house next to mine yesterday. His family is having him buried today as if they have been waiting for him to die all his life. I see them offering drinks and food to guests with smiles on their faces. Shameless fools. Even the sun hid behind a grey cloud as if in mourning. It has been a bothersome thing for me since I happened on the spectacle of the pallbearers and trumpeters swinging their bodies to the melody of their hymns in their shiny purple and black imitation suits. Their grim faces house ceremonial smiles, and perky black bow ties hang loosely from their necks. They swing the coffin from left to right, and right to left, in a dance that looks like a ritual. I imagine how practiced these men and women are in the act of burials and spit my resolve to beg my family never to allow such a waste when I pass on.

3.

About three years ago, my brother-in-law died, and I remember passing up the chance to attend his burial on reasons similar to this pretentiousness. I remember sitting on the spectator’s stand at the service of songs, watching my sister and my nieces and nephews as they were bestowed the burden of performing their grief in front of an audience. I remember the anger that clogged me as I stormed out of the place. Isn’t grief supposed to be personal? A woman loses her husband, some children lose their father, and the first thought that hits us is that they must perform their grief to people whose opinions in these kinds of things are supposed to matter. My body taught me how to keep my grief inside about fifteen years ago, after my maternal grandmother was pronounced dead and my household was engulfed in mourning. I couldn’t bring myself to cry. My grief found expression in the little things that reminded me of her. I didn’t shed a tear while they were committing her body to the ground. About two weeks later, while hungry and remembering the one person who, whenever I told her about my hunger pangs, would cradle me in her arms while she scoured the house for something to eat, I wept in the privacy of my room. I still feel, like I felt back then, that there is dignity in grief that is privately expressed.

4.

The first time I noticed the man, it was on the eve of my second night in the area. I had just moved in. He’d sit with his chest bare on a small bench in front of his house as if he was some security guard. I was uncomfortable, but I would soon learn how to live with his big eyes stuck on me. Later on, time will break the soliloquy between his eyes and my body; my housemates will teach me how to be respectful and say Ekaaaro and Ekaaale in greetings every day and night as I walk by. His replies, usually very frail but never late, would come so fast, it was as if he had been waiting his life for the greeting. Because I was the sort of person who overthought simple things like this, I stopped greeting him.

5.

His eyes didn’t stop following my everyday waka-abouts, his body didn’t change positions, nothing about him changed. I allowed my body and the obeisance his eyes gave to continue their relationship. I imagined the kinds of conversations this man allowed himself to have and hoped that my greetings never mattered to him. I wondered what he thought of my decision to stop greeting him and convinced myself that I didn’t care about who he was or what he was or why he was that way.

6.

Some weeks ago, I almost ran him over. It was late at night, around ten-ish. I was coming home from an unlikely Arsenal victory against Leicester City as the new season of the English Premier League started. I didn’t see him walking in the dark; he was bent, held by his wife, attempting to cross from the grocery store adjacent to his house. In my pause after almost clashing into them, I observed the pain chewing at him with each stride he made. I said my Ekaaale and walked by, giving him no extra thoughts. But as I walked by his house the next day, I noticed the man wasn’t there. And for a moment, I found myself in the middle of a cruel life joke. Until his absence, I never imagined how important it was for me to always have his eyes following me. His verandah was empty and colorless and I wished I could see him again to resume the greetings I had suspended. I had become comfortable with his presence so much that my body craved him feverishly. I didn’t have to wait for long. The day after, he was back. His face was slimmer. His eyeballs were more sunken into his skull, but he wore a smile for each person who sent a greeting his way.

7.

From then, my mornings and evenings became punctuated with ceaseless greetings. The curiosity I had abandoned before took a hold of me. I started questioning everyone I could find. Who was this self-appointed vigilante of this street of ours? Why was he so invalid? No one seemed to have a story about him. Whenever I asked my housemates if they knew something about him, they’d shake their heads, each beginning with a story of some kind of awkwardness they had experienced on the basis of him watching them. Maybe he is a serial killer planning his next kill says one of them to boisterous laughter from our group of three. Another tells me to ask him myself if I couldn’t tame my curiosity. I considered the possibility but, despite my new greet-relationship with the man, I couldn’t bring myself to an agreement. So, from then on, I became the watcher, walking past his house many times, in the pretense of running errands, so I could catch a conversation that might give me some clue. I considered befriending his wife, but unlike him, I hardly ever saw her around except late at night. I soon gave up, but around the period when I stopped stalking him—despite the competition his eyes gave me—he disappeared. Again.

8.

Anytime I saw his wife, I considered asking her where he was, but the drop in her gait, the black bulges under her eyes dissuaded me. With time, I became used to not seeing him, used to life on our street without him dutifully watching, and though my body felt naked without his eyes following me, I accepted the possibility of never seeing him again. One hot evening, some boys from a house down our street allowed the noise of their argument to travel up to my room. I tuned my ears to the frequency of their banter and that evening, I learned the identity of the man, damaged while in service of Nigeria in Maiduguri. He was no military man, but a volunteer vigilante. I learned that he had lost everything, his wife and children especially, to Boko Haram. The boys debated his age: One said he was fifty; another said he was forty-five. I didn’t care much for the range of his age as I did his looks. What could have eaten a man of forty-five or fifty so deep as to have accelerated his aging? Answers to my questions would be thrown to the gutter when the boys’ conversation graduated to the woman I saw with him, the one I mistakenly called his wife, and assumed to be younger than him. According to the boys, she was his older sister who had taken it on herself to take care of him after he became invalid from the war.

9.

Years ago, sitting in a church service listening to the pastor speak about taking care of our loved ones, I felt accused. He would go on to tell members of the congregation to give their family members a call that night and tell them how much they meant to them. When the church service was over and people brought out their mobile phones and began to mush over their loved ones on the other end of the line, I felt isolated. I thought about my family at that moment, and I couldn’t figure who I’d like to call: my mum, my dad, or any of my three siblings. I had not visited home in so long, I was beginning to forget the sound of my mother’s voice, the depth of the advice my father liked to give, and the crackle in the laughter of my siblings. I had chosen a life in isolation, a life with no responsibility: I canceled all possibilities of romantic relationships; I alienated most of my friends, all for the simple reason of not wanting to be burdened by anyone else’s issues.

10.

I thought about my life and the decisions which had brought me to where I was, and I couldn’t help seeing the connection between myself and these people who I was blaming for the speed at which they buried their man. Again, shame enveloped me, especially considering my final interaction with the man: two days before he died, I walked past him without regarding him, assuming that he would always be there.