People Generations

Ógbuágu: The Lion’s Killer Depression

“Did I resemble my father now with my depression? Did he see me every morning and feel arrested by the familiarity?”

In Igbo, Ogbuagu literally translates to “a lion’s killer.” It doesn’t entirely suggest cruelty, but bravery. It is the highest title that can be given to a person in Igbo land, and reserved only for the strong, the brave—those who walk into a lion’s den without saying goodbye to the people they left at home.

*

I began to know my mother in my early adult life. Before then, what I knew of her was in a stream of memory so thin it was difficult to distinguish it from imagination. Her body in a wedding dress, laying eyes closed in something metallic on four wheels, right in the center of our living room in Mbieri, me and my only brother, and some other people whose hands rested firmly on our shoulders, walking around it. That scene was from her lying in state twenty years ago, on an otherwise ordinary day in June, a day without wind or clouds, as though the very skies were in mourning. The entire village had shrunk itself, the market women, their brothers and husbands who returned home with the smell of gin heavy on their breath, their children who slept through their noisy arrival, all of them gathered into a chorus of sorrow, uncertain too, by one look upward, of God’s mood.

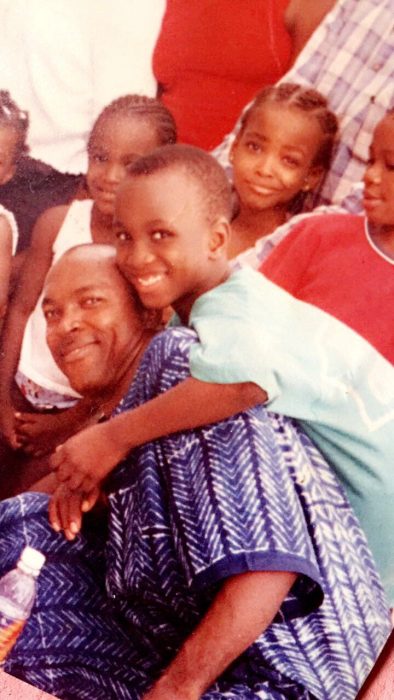

My siblings and I were dressed in a blue Ankara fabric, and after the walk, we disappeared. The next place I found myself was behind the skin of a boy who saw pain not as a thing of occasional distance, but one of the same flesh, a boy who was limp, whose hairline was thinning, shifting backward, and answering sternly when his father called him ogbuagu.

*

One evening, after I turned nineteen, my father called me into his bedroom, where he was sitting on that brown armchair with his legs spread out, both elbows firm on his knees; the ceiling fan played a tune to a cheerless audience. Thoughtlessly, I gave my weight to his bed. It is a familiar image of my childhood, the pose: his fingers clasped; his head tilted; his eyes shut tight as though imagining the things he would say or, having imagined them by now, forcing them out of memory and into words. It was the pose he struck after a wrong had been done, when a scolding was required, when a moral was ready to be learnt, or when a bad grade was brought home. Now, I could not feel the heat of his anger or the shame in my action. I felt, instead, a profound sense of tiredness, mighty in the air and borne even by the room, as though everything it harbored understood.

“What is going on, Ogbuagu, please talk to me, why are you like this, what is happening to you?”

My father’s face was raw, naked with worry, harder now to hide behind the currency of any parental power. It was a face subdued by love, a begging love, a love that might have belonged to someone so shamelessly besotted, a love that might overflow into obsession and consequences and, without firm reconciliation, turn into a tale of isolation and utter pain.

For days, I had been moving around the house slowly but not uninspired, the way a guest might be conscious to do the right things—to try, to the best of their abilities, to rob the house of their presence, or to perform simple acts of kindness for which they were sure, in the event of their exit, the house will echo in their names. I’d said my good mornings, made my father his morning tea with honey and four slices of bread. Whenever he tried a joke, I would, with that same helpless sense of a visitor’s duty, squeeze a boneless smile out of my face; a smile that would disappear as easily as it had appeared, aware not so much of the joke but that something was said and, of me, something was required. It hadn’t occurred to me that living required permission and resisted imitation; that I had to approve, to some degree, beyond the physical registration of the things my eyes met. That beyond existing, even the inanimate had their own lives: the curtain swaying on warm evenings; the kettles and pans that surrendered themselves; the living hiss of doors and windows being opened daily.

“What is going on, Ogbuagu, please talk to me, why are you like this, what is happening to you?”

That evening I recognized the pressure of words, how their weight can sometimes make anyone stutter. My throat ached with dryness, a direct result of forgetting how to form and speak words.

Nothing was wrong, I finally said to my father, and he looked up at me, searched my face, and found the lie. I knew the minute it registered and, responding with shame for the first time, I bowed. There was, of course, something wrong with me. I could tell almost the way one feels goosebumps; I could trace the very frequency at which my heart fluttered every morning, scared and ashamed of something intricately woven inside of me that it was difficult to neglect, the morning sun like a little pill I couldn’t swallow without it shedding its chalk on my tongue. I was unhappy, but beyond that, there was something else, and with it, a shyness to confront my own confusion over the state of my life. Although unhappiness for me, in the past, had settled itself with bolts of loneliness, of failure, an acute sense of boredom, I had never felt this tired.

*

Humans have multiple faces. Do you understand? You can look like an uncle when you’re sad, like an aunt when filled with anger, or like a grandparent when quivering with laughter. There is never one real or true face. Did I resemble my father now with my depression? Did he see me every morning and feel arrested by the familiarity? I wanted to see with his own eyes—see myself for what I was, and feel at once the things I might never be. It was true that I was not masculine enough, that I did not have the decency to juggle hardships in a very brave and undefeated way, the way he did, the way I ought to, and in a way I felt threatened by a frisson of fear and terror. I wanted to repulse my identity, remove the name Ogbuagu from my father’s tongue, erase the years that I’d answered to it, letting him pick me up and throw me in the air, my laugh cackling and entering the spaces between his teeth as he smiled. I felt, at best, a fraud and at worst, a failure, answering to that name. Some mornings, I’d struggled to pull strength from my name, from an idea that exists almost as a religion, and in knowing that because I was formed of these concepts, I might, if I tried hard enough, find some semblance of truth in them. If my father thought I was strong and brave, then perhaps it was true.

I asked if you understood the multiplicity of a human’s face because it is good to visualize what a human face can do with several emotions. But I myself had been faceless that evening, nestled in a place of emotionlessness, a place wherein its governing laws and standards hadn’t been taught to me, but I’d found myself practicing with such accuracy. However, I wondered whose face my father was seeing as he begged me, as he sobbed in jerks—the hissing sounds of a clogged pipe characterized the room, my silence a sincere response—as he bargained for my happiness as though it was his next breath, and by God—the God who was without a mood that June day in 1997—he was to give it to me. Did he see himself from the days and weeks after my mother died, and was this plea an attempt at salvation? Was he saving me for himself?

I would not say that my father got over my mother, because he didn’t. Often, on simple days, when conversations emerged without the intention of taking on such weight, sometimes on his return from work, where a simple welcome offered got him to surrender the particulars of his day, I tailed him up the stairs as he made his way to the bedroom, and collapsed into that brown armchair, to tell me stories about my mother. His stories were full and deft, precise with dates and emotions, which often left me feeling as though the stories had not been lived but created instead, with the intention of a near future. He was telling me stories of the life he was yet to live with a woman he hadn’t met, but was convinced existed out there, somewhere, waiting, just as he was for her, with mild-hearted effort, unstained with any transactional anxiety.

Now, my father was talking about my mother, telling me what her death meant to him, and why I must not die. Once, another tale of my mother had started through the prospect of bread. In the observation of how I buttered my bread, my father had begun telling me how it was another way I resembled my mother. I couldn’t say anything as I watched him speak, selecting his words, stammering through memory and other times snapping his fingers at me to remind him of the words he was yet to say, although this seemed more like a cheap and desperate attempt to get me to talk. I’d imagine he and my mother had those days too, when they completed each other’s sentences, when she could identify the first hint of anger on his stammer. In his stammering, impatience swelled up in the room like yeast.

In an awakened silence, sitting among the colors of my father’s bedroom, I waited for something to happen—aware of the presence of something new and altogether familiar enough to hide itself behind the curtains, underneath the bed, and in the tight spaces between books on the shelf. It was my love for him, this begging love. I walked up to my father and left my hand on his shoulder. He was still sitting, still with his elbows on his knees, his face meeting his clasped hands as though in a prayer. His breathing was not soft. I started to rub his back, attempting to soothe, feeling ridiculous, almost mocking, really, for it all. In the air was his smell, my depression, the unbelievable weight of doubt over what my life should be, but I brought my lips to the side of his face, and said that I was fine. He did not acknowledge nor did he question further, and so I decided it was time to leave.

In the center of his bedroom, I turned back to him, and if he had moved an inch, I wouldn’t know. Testing a smile, I’d said again that I was fine, which was not, of course, strictly true. It was something to say before I walked toward the door, leaving behind my father’s breathing that seemed too close to a contradictory performance, a breathing that was as though life was being leaked instead, slowly, the way a faucet releases the very last drops of water it had been allowed.

*

I wake up to the sound of a horn. It is an uncontrolled, steady clang that suggests the image of someone’s palm spread out on the steering wheel while murmuring curses at whoever it is that is in their way. Soon though, I recognize it: Our neighbor has returned and their gateman is in the backyard, or has gone to buy cigarettes, or is fast asleep—anywhere that isn’t by the gate when his Oga has returned, when I am unduly evicted from a dream.

I’d been dreaming of the day the villagers didn’t know what mood God was in, but this time we are outside, our feet planted on earth red with anger, in wild-blowing dust, and an assembly of white plastic chairs and canopies whose rental addresses were printed upon them in red ink. In front of me a tree stood, its leaves bright and expectant. There is so much noise; a deliberate discomfort from movements, from music, from people who proved that being alive necessitated a sort of performance, their contribution to the fabric of community life. I cannot make much of the air until I see my father, naked in sorrow, a ringing from his throat that is a four-clear-note in succession. It is strange, even in my dream now as a young man weeks shy from twenty-four, how close to me the ringing is, and then suddenly, with the mechanism of a blink, it comes to me that it is the same sound from when he called me into his room, begging me to stay alive when I was nineteen.

I stand up, wipe night away from my eyes, and in no more than ten seconds, my house returns to its rare, frightening silence, and from my window is this: The neighbor’s gateman, after locking the gate, is running a quarter-mile to meet his Oga, and is standing by the opened door, about to throw his body in greeting with a split consciousness, half from casual domestic respect, and half from guilt.

It is two months now since I have been back home, in Lagos, a city alive with chaos, decaying even from the very treasures it prides itself with. Home never really surprises you. Everything is almost in order. Everything is nearly fixed. The repetition of routines goes beyond a sense of boredom and offers immeasurable peace. You know where the kitchen knife stays, no matter how long you are away from it. But isn’t that the premise for leaving it behind in the first place? Not to know where the knife is later on, but because you long to see something other than the tree that pushes at your window every morning, those power lines that entwine with the leaves as the city’s blindness melts into morning light. It is why I had to run after I turned nineteen.

Today I am stunned by the familiarity of home, its makeshift usefulness. The sense that something is missing, an idea that, no matter how calculative, how much I bargain, cannot be reconciled. I walk around in my underwear, with no particular sense of purpose yet, with Sade’s voice floating through my speakers, hitting the walls of the hallway that, except for a string of cobwebs, was empty. I open a door, peep inside, and then close it. I have the house to myself. But I feel alone in a way that shrinks me inside of my skin. The room my sisters share is empty, an eyeliner mishap proud on the tail of the bed sheet. A white towel rests over a wardrobe door slung open. In my father’s room, next to that brown armchair, is the closet door, and I am going through it, inhaling residues of his smell—something feminine and clean—and imagining myself in his clothes. I pick a pink shirt from it, and confront the image of my father helping me with the cuff links, his back bent and squinting into the tiny hole; how he will arrange the collar of my shirt, tease me over the length of my pants, a tease incomplete without a head shake, a boneless smile, a time in history, a story of my mother. I take the pink shirt off and wear a black T-shirt instead. I tell myself – spotlighting a sense of satisfaction, although unnecessary – that it doesn’t have collars or holes for cufflinks.

The morning sun cuts a triangle through the open curtains and leaves it on the floor of my father’s bedroom. I stand in the center of it. Then I imagine it happening. For reasons unknown to me, the idea of receiving a call that will deliver bad news presents itself. Someone must’ve died. My phone will ring, and I will have to drive somewhere. Already I could feel the weight of the steering wheel in my hands, my thighs burning its adrenaline into the accelerator, the tires dipping into potholes. I am racing the car and could see the trees that line the streets, merging into one another at my speed, catching bits of silver from a sun that could make human arms leak sweat. I could see the living room crowding again, human smells and wails unsettled therein and moving out into the street, the hinges of the door squeaking with humiliated astonishment.

I shake myself back into the present: the low hum of the air conditioner, the fluttering fragrance of a vanilla candle, the unpolished shoe by the leg of the bed. Outside in the backyard, a line of laundry hangs in the air. Then suddenly, my phone is ringing from my room, stealing the silence of the house, beyond my father’s room, outside the illuminated triangle of sunlight. I begin to cry.