People Losing My Religion

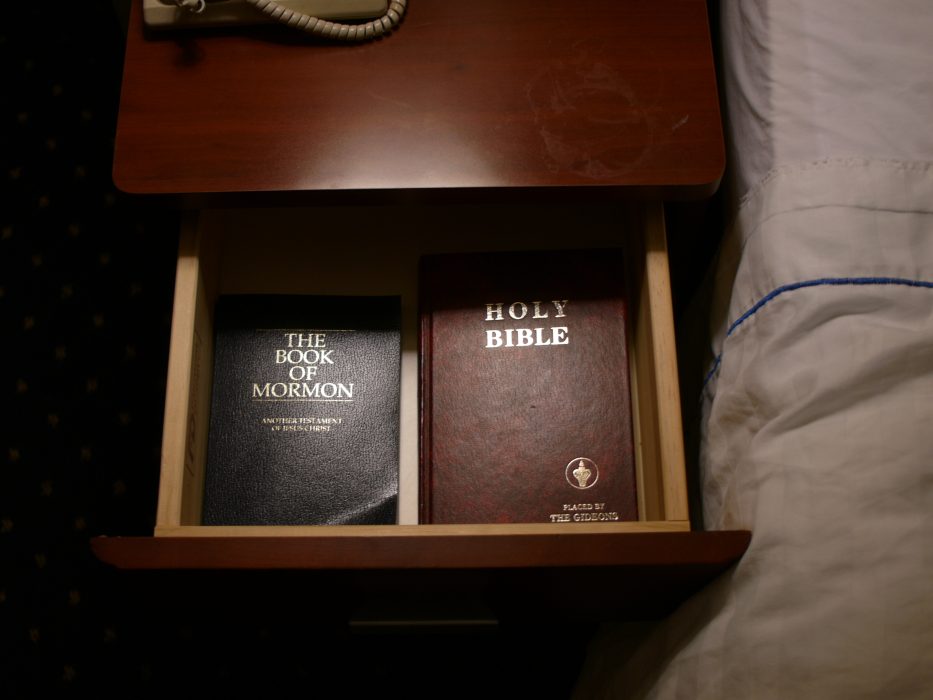

The Book in the Box

Getting trashed was my way of announcing who I was: not Mormon.

When I left for college in 1984, I packed some things in a banana box I brought home from Safeway. The box was sturdy, with useful handles cut in the sides, and large, less useful holes at the top and bottom.

I don’t remember what I packed in it, but I remember what I didn’t: my Book of Mormon. It was part of a set of scriptures I had been given by my mother years earlier as a Christmas gift, a personalized set in faux leather, which she imagined I might read and study for years. For her, a lifelong Mormon who had leaned heavily on the faith during difficult times, there could be few more important gifts to pass along to her eldest son.

I was eighteen, and leaving my hometown of Gooding, Idaho, for the University of Idaho. I had spent hundreds and hundreds of hours in Sunday church services at the tan brick wardhouse on Main Street, which is to say nothing of Family Home Evenings on Mondays, youth group on Wednesdays, and all the other church-related events that filled our lives. As much as anything, it was this I was determined to leave behind—the church’s relentless command over the hours of my life, the enforced devotion, the crushing boredom of all that worship

I was on my way, I knew, to join the army of “ex-Mos”—ex-Mormons, perhaps the largest single branch of the church’s American diaspora. My departure would be abrupt and final, I thought, a clean break. And, though I was certainly undergoing a period of spiritual questioning and doubt, the fuel for this departure was something much more earthy and earthly: beer.

*

When I was fourteen, I attended a youth conference at Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, a church-owned school that is now called Brigham Young University-Idaho. The conference concluded with a meeting where teens stood to “bear their testimony,” often emotionally or tearfully, of their belief in the Gospel. So many other teens had done this, including friends and peers and older boys I admired. I hadn’t intended to get up and speak—though I had borne my testimony frequently over the years—but I was swept up that afternoon. An emotional grass fire spread among us, and it did something to me that I still struggle to explain: It filled me, in a way that felt concrete and physical and certain. As I stood before the others, trembled and wept, I swore that I believed the Gospel to be true, that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, and that we were led by a modern-day prophet of God.

I really did believe those things. Within just a few short years, I really did not. I could sit in a testimony meeting, utterly unfilled, my mind picking apart the things that were being said. Though I have thought through my reasons for this, and though there are many of them, this void has always operated just as my faith did—as an intuition or instinct. I felt it before I could explain it: I no longer believed.

The beginning of this transformation was more cultural than theological. I wanted to stop living as a Mormon as much as I wanted to stop believing as one. My closest friends were not Mormons, and some of them came from families that considered the church weird, cultish. I was self-conscious about feeling like an outsider. One of the elements of Mormonism that was strangest to outsiders was the series of rules for healthy living called the Word of Wisdom, which includes a prohibition on alcohol, tobacco, and coffee.

For me, the Word of Wisdom highlighted precisely where the forbidden fruit hung. I was a junior in high school the first time I drank beer, in the parking lot at the high school during a girls’ basketball game. Coors Light. The Silver Bullet. I remember being thrilled by it—by the bitter, yeasty flavor, by the transgression, by the loosening in the mind.

By the time I graduated, I was drinking beer as conspicuously as possible. My friends and I went to keggers in the sagebrush desert. We found a little store that would sell us cheap, musty-smelling cans of Carling Black Label without asking for IDs. We “dragged Main” with six-packs at our feet. Though I was surely not alone, among the legions of teenagers getting wasted, I must have been the most concerned with wanting to let everyone know that I was getting wasted.

*

The day before high school was to let out for Christmas break during my junior year, a couple of friends and I went out at lunch and glugged down Early Times whiskey mixed with 7-Up. I returned to school utterly trashed; there was an assembly, where I made a ludicrous spectacle of myself, reeling around and spouting the lyrics to a punk rock song that included exhortations to kill your parents and teachers. The football coach hauled me off in front of the whole student body and deposited me in the principal’s office, where I proceeded to vomit into the wastebasket while waiting for someone to come pick me up.

That someone, it turned out, was our ward bishop. Whose daughter I was supposed to escort to a formal dance in a matter of days.

I was embarrassed about all of this. But I was also—on some perverse level—not embarrassed at all. That spectacle was a part of a longer-term project in which I was, loudly and stupidly, announcing something about myself: not Mormon.

This also meant I was marking myself off from my family. Word of my drunken outburst had reached my mother, and I remember her asking me, baffled and hurt, why I would say something like that. Kill your parents? I didn’t know. I didn’t want to kill anyone, of course, but I was chafing against everything.

It was not the first, or the last, time that I would realize I was breaking her heart. We had outrageous fights in those years. I hurled my rebellion in her face with a spite that shames me even now. She threatened to throw me out on more than one occasion, and, looking back, it is a testament to her love and patience that she didn’t.

Wrapped up in my mother’s love were lessons that I would carry my whole life, lessons that grew out of the Mormon faith as surely as the Word of Wisdom that I was so energetically flouting. I didn’t recognize this while I was pursuing binge drinking as a replacement identity: The idea that the departure would be clean or simple was as naïve as the belief that guzzling whiskey at lunch would give me a manageable buzz. It was only years after I had left the church that I understood that some things you simply cannot leave behind. They are already inside of you by the time you feel how powerful they are.

For me, luckily, these remnants of the faith have been mostly positive reminders of the importance of hard work, kindness, determination, and love. My mother, my family, and many of the Mormons I grew up with demonstrated, by example, their fundamental belief in the importance of family, by loving me even at my most rebellious.

That fall more than thirty years ago, I arrived at the University of Idaho to discover something unexpected in that banana box, visible through the rectangular hole in the lid: my Book of Mormon. Smuggled in by my mother. My name stamped in gold lettering on the cover.