People Unreported

Nineteen Slaves

“I thought I would be able to claim some exemption from the darkest time in our history.”

One by one, the boys of the high school basketball team strode across the gym floor. This was different from the game, where they moved constantly, blurring together with this shared goal of getting the ball to a place, ignoring the crowd. Now they faced us, and stepped forward one at a time, slouching in the careless, disinterested way boys do when they wish to appear unaffected by nerves, leaning like heavy trees after a storm. Screeching with laughter, the entire student body took turns bidding on the boys, besting each other’s offer by a quarter at a time.

“The South will rise again!” someone screamed from the back of the gym. It was the boy who brought an empty Coke can to every class for his tobacco spit. We’d been continually reminded of the slave auction with posters printed in the computer lab, then stuck to lockers and bathroom walls, pictures of old-timey iron shackles and chains around their borders. Attendance was mandatory, according to the poster. Just like pep rallies, they said.

The boys would be slaves for a day, carrying books and running to lockers to fetch hair brushes and folders between classes. When the boys were sold, a member of the Future Farmers of America ran across the gym floor, waving a Confederate flag. In the parking lot outside of the gym sat rows of mud-spattered trucks absorbing the afternoon heat, identical flags hung in back windows, portrayed on stickers adhered to bumpers, all fading in the full sun.

We called it “the Rebel flag,” and those who owned one spoke about it with a sort of inherited pride, like accepting thanks for a job well done, a job done by someone you’d never met. It was okay to talk about these things, to throw these words around, to trumpet the virtue of this place, the South, that we’d somehow failed to exhume and reanimate, decade after decade, to nurse back to its former strength. No one was offended by this kind of talk: All of the faces in the high school gym, the hardware store, the church basement, were shades of sunburned white.

We lived in what had been a sundown town—a place where black people were warned not to stay for long, on the threat of shooting or hanging. “Whites Only After Dark” claimed signs on the roads into town, and though they had fallen or been torn down years ago, the understanding remained. We lived in the midst of rolling green hills and rock formations, rotting buildings, and the former World’s Smallest Post Office. The area is known as Little Egypt, and many of the small towns enclosed in its triangular borders were named after cities in Egypt, due to their placement between where the great Midwestern rivers meet.

As in Egypt, there had been a mass exodus, and our parents had watched as jewelry stores and family-owned markets closed after years of steady business. You had to drive to the next town to buy hamburger buns, then two towns over. The local theater’s marquee, which once advertised Gone with the Wind , spelled out SUTTON PLUMBING in broken plastic letters surrounded by empty bulb sockets. The seats where my grandmother sat and watched Vivien Leigh refuse to take Mammy’s advice and eat a little breakfast before the barbecue at Twelve Oaks were now used to store plumbing equipment. “It’s haunted,” my grade school friend, descendant of the Sutton dynasty, whispered to me on a sweltering summer day before third grade as we peeked into the ancient theater. The dusty velvet seats, spewing bits of stuffing and springs, held shrink-wrapped toilets. The lidless, yawning mouths of the toilet bowls appeared to be shocked by something they’d seen on the empty screen ahead.

One of these Egyptian-inspired towns was famous for its total failure to thrive, a slow and painstaking rot that began with lynchings and riots, and ended with a boycott of white-owned businesses. Packed into rusted cars, we stalked around the shell of what had formerly been Cairo, Illinois. We climbed through broken glass windows to open desk drawers and paw through their aged contents. We called it “spelunking,” lowering ourselves down into musty places that had long been hidden from light. We thought the burned-out library vomiting moldy books between the holes in its floors, the shattered windows and faded signs of the office buildings, empty lots patterned with remnants of ornately tiled floors, and the trees growing through the middle of the sidewalks were romantic and terribly sad reminders of a rich past, like an abandoned house whose inhabitants have all forgotten to come home, or perished together in some noble way, holding hands against their sudden fate.

Our history teachers were assistant football coaches, retired septuagenarians, and worn-out teacher’s aides. For forty minutes each week, we studied the same proud moments in American history. On an endless loop, pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, shared a plump Thanksgiving turkey with smiling Indians, and dumped tea into the Boston Harbor. Over and over again, we recited facts about the Revolutionary War, that valiant effort which gave us control over our rightfully begotten land. The Emancipation Proclamation section of the book signified the end of the school year, and the next year we had a different history textbook (not new, never new), and a different disinterested authority figure to keep us in line as we worked our way through the same events again.

There were sparks of skepticism in my education, brief shimmers that died out in the gentlest breeze. Injustice, we learned, was a part of life. Columbus had killed some Native Americans, but not all of them . Settlers had forced tribes from their lands, marching them across the Trail of Tears, but then they had been given reservations to live on . Africans had been stuffed into ships and sold into generations of slavery, but then they had been freed . There was a vague sadness to these actions and their resolutions, something bottomless and inconsolable, like when we used to go swimming in flooded strip mine pits where we knew old drilling equipment had been submerged, but how far down? And would it ever touch our feet? Like the idea of forever, like the idea of space, there was no end to it, and no comfortable way to think about it. It swirled on and on, a sea of doors opening to more doors, into the dark. Why pull the latch on something that led to nowhere? Why ask a question that led to more questions? In the strip mine pits, you just kept swimming, and trusted that whatever was below was very far down.

I went north to Chicago after high school, in an Amtrak car with a broken toilet. The smell of sewage filled the car and permeated my lungs for six hours, because I was too afraid to ask if I could sit somewhere else. My roommate and I took turns washing the pee smell from our hair under the low-pressure trickle of cold water in our shower. We shared a futon in the bare front room of our new home, living out of our backpacks until the moving truck stuffed with our possessions caught up with us. For the first week, we couldn’t sleep through the sound of fire trucks and the noise on the sidewalk below, outside the doors of the liquor store. I cried because I missed the screams of cicadas and the hollow taps of walnuts pelting the roof on breezy nights. Down on the sidewalk, at two in the morning, a man yelled “Somebody sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to my black ass.” We closed the windows and sweated through the night, preferring the muffled heat to the noise and smells of hot sewer drifting up from the street.

It seems somehow fitting that I was deposited with a belch of rancid air onto the gritty streets of a place that had been named for its bad smell. The French explorer Robert de La Salle had written in 1679 of the place known as Checagou, or shikaakwa to the Native Americans who lived there, in reference to the abundance of ramps growing on the shores of the lake, shedding their garlicky stink into the breeze. A little over two hundred years later, Chicagoans would create a new signature stench by depositing rotting animal carcasses into the lake slips near the busy stockyards. They would forget about these deposits, pretending not to notice the bubbles rising to the top from the several feet of decaying offal below, a sludge that still boils today.

Everywhere I went, I felt I carried the stink of small-town secrets. Coworkers made fun of my twang, mimicked the way I split words into extra syllables. Friends joked that every street in my town was named County Road 101. People asked if I’d ever seen a black person in my town before. I answered honestly—only when they played our football and basketball teams—then laughed with them at how ridiculously hick my town was. Laughter meant that I was no longer a part of that place; I’d moved on and could see it clearly from on high. I was more than just a white girl from a podunk farm town; I was better than all of that. I laughed long and loud, until I could feel it all sink to the bottom.

A Family Tree

The first thing you learn in library school is how to question your source, how to spot the pieces that look too new or perfect or off-color from the rest of the structure. Lies are the cornerstone of history—they are also the anchor, the bricks, and the beams. Sorting through pieces of historical information—finding the truth of the matter—is a skill that remarkably few people care to develop, which can be proven with a quick glance at the most popular Yahoo Answers. When you test the reliability of your sources, you’re looking at facts without emotion, you’re turning off the rush of dopamine in your brain that rewards you deliciously when you read something that supports what you already thought.

History is a story told by a witness, and since we are imperfect, our stories are shaped to fit comfortably into a predetermined space. After years as a trained archivist and skilled researcher, I trusted myself to find the truth about my family. When exhaustive research revealed no slave schedules, no plantation ownership, barely evidence of hired nannies or field hands, I thought I was close to discovering that there was more to my family, that our story was going to be different from the stories of other white Southerners. I thought I would be able to claim some exemption from the darkest time in our history, even as I informed my genealogy clients about their ancestors’ involvements and connections to slavery. The available evidence supported my fantasy visions of kind, open-minded, abolitionist ancestors, though whether they had not taken part in slavery because of high moral character or low financial means, I couldn’t be sure. When the historical research is going the way you want it to go, there is no greater satisfaction. Common sense, however, makes a disturbing noise. No matter what I found to further my case of historical innocence, something was always bubbling to the top, some ancient decay, weighted and submerged, troubling the surface.

My husband and I sat at our dining room table, sucking our cheeks to generate enough spit to fill the tiny plastic tubes that came with our Ancestry DNA kits. I’d built out each of our family trees as far as they would go, and hoped that these little containers of our spit would sprout some new branches in those places where I was stuck. The tubes contained a blue dye that ran down when you clicked the lid shut, turning your sample into a preserved, gelatinous goop. We shook our spit tubes for thirty seconds, according to directions, sent them off in their little boxes, and waited.

I wanted a culture, something more compelling than what I’d already found, which was a whole lot of poor farmers from Ireland, Switzerland, and England who became poor farmers in America, taking advantage of cheap land that had so recently belonged to Native Americans. I was hoping for an interesting story, something more exotic than “white” and “southern.” I wanted something that didn’t conjure images of biscuits and gravy, of Confederate flags, gap-toothed smiles, and hunting rifles.

Weeks later, our results came back. The map of my husband’s ancestry spanned several continents: Europe, Africa, and Asia, connecting him to his distant cousin, social justice folk singer Arlo Guthrie . My map was centered entirely on Europe, connecting me to my distant cousin, George H.W. Bush—Papa Bush himself—whose ancestral line, carefully constructed and proudly shared due to his status as America’s 41st President, led me to a new branch of my tree.

My Homeland Tennessee

Peter Cocke carved out a home in the curve of the Cumberland River in 1796. His brother, William, had been elected to speak to Congress on the behalf of the residents of “Frankland,” a territory west of North Carolina. William argued in favor of statehood for Frankland, in order to secure Congressional protection for those who had wandered beyond the western line of North Carolina, and out from under the protection of its militia. Native American villages still dotted the landscape, and attacks on settlers were common. In the end, Frankland’s legitimacy was rejected for the sake of the ratification of a larger territory, the state of Tennessee. Peter, along with other pioneers, were free to continue West, patenting large sections of land along the way.

On 1,500 acres in the elbow of the Cumberland—near present-day Clarksville—Peter’s family prospered. Their plantation, most likely cotton, thrived. Grown sons were given their portions of the land on which to support their own families. Peter’s children built homes and farms; they moved north into Kentucky, and then further north into southern Illinois. They married, had children, and their children did the same, on and on through the decades, until eventually, there was me.

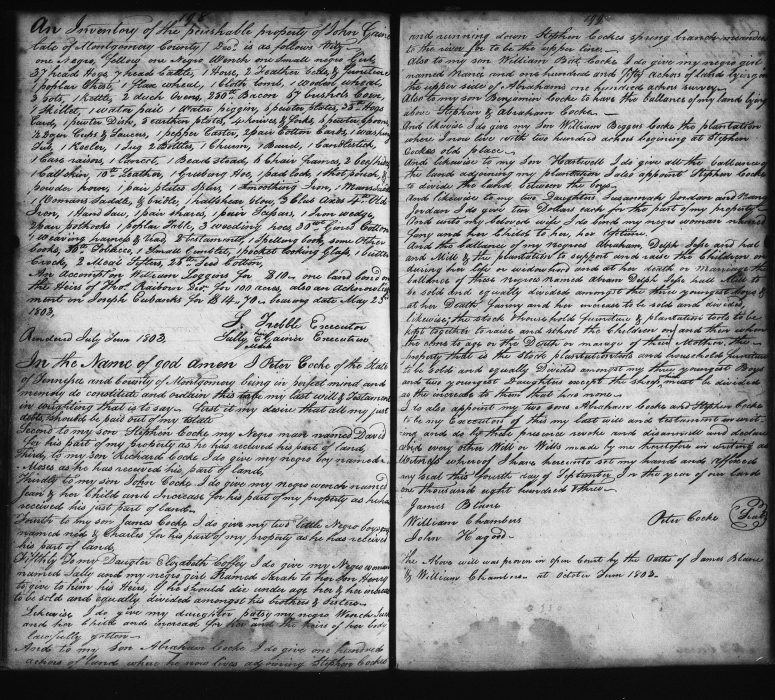

By frontier standards, Peter Cocke died a rich man. He owned hundreds of acres of land. He owned twenty-eight heads of cattle, seven horses, sixty hogs, and eighteen sheep. His home was filled with walnut furniture, kettles, pots, looking glasses. His barn was filled with plow shears, axes, hoes, wedges, and iron chains. He owned one copy of Burket’s Explanation of the New Testament by James Daniel. He owned one copy of the Bible, and he owned nineteen slaves.

Their names were David, Moses, Jean, Ned, Charles, Sally, Sarah, Lucky, Nance, Fanny, Abraham, Delph, Jesse, Hall, and Mill. Lucky and Jean each had one child, and Fanny had two children.

Ned and Charles were described as “my two little Negro boys,” and Sarah was described as “Negro girl.” No mention is made of their parents.

Each slave was willed to Peter’s sons, daughters, and his wife, with careful legal language used to ensure that the slaves—and all of their future children—would be property of the Cocke family, in perpetuity.

Each slave is listed in Peter’s will, dated September 4, 1803, as Peter—my seventh great-grandfather—neared the end of his life, at the age of sixty-five. Together, described as “19 Negroes,” they top the list of items in an inventory of Peter’s possessions, created after his death, in January of 1804. They remain there in the folds of history, with the horses, the cattle, the sheep, the candlesticks.

An inventory of Peter Cocke’s possessions.

Protection

The tennis courts of a century ago are long gone, but the lawn behind my mother’s house is still a wide rectangle of perfectly flat land, land her neighbor sometimes mows for her just because he likes to mow. If you sit on the porch swing, each and every passerby waves from the windows of their trucks as they creep past at ten miles per hour. This is a place where you walk down the road to borrow some eggs or milk for your cornbread, where your neighbors peek out of their windows and make sure your kids haven’t fallen out of the tree they’re climbing, where someone calls you when you leave your back door open.

My mother’s house was built in 1910 by a wealthy family. In the walls, builders enclosed pages of magazines—time capsules, buried one sheet at a time, bright snapshots of a profitable American life. The profits that built the three-story home were from years of success in railroads. The first and longest railroads in the Southern states were organized and planned around the availability of slave labor, built by slaves either purchased by railroad companies or rented from their masters. Rail companies created detailed contracts for hired slave labor, indicating how owners would be compensated for their property in the event of an accident. Accidents were common, and commonly fatal.

It’s easy to imagine the disappearance of the house where I grew up, and the drastic changes in the landscape, within an alternate version of American history where slavery never happened. It’s easy to imagine the ripples in history reversing: the slow growth of railroads, cut down by the absence of the glow of riches and fortunes, homes disappearing, towns shrinking, condensing. Each step away from the path of slavery creates a different America, a nation none of us would recognize. Each step on the path to slavery created the America I live in, the life I benefited from. Is there any place in our nation not affected by our historical shame? Was any part of the alternative possible, was there ever a point in the chain of events that would have allowed a different outcome?

Life on the frontier was dangerous and difficult, even with strength in numbers, with bodies to build homes, develop the land, care for the crops, and guard the livestock. When the cotton gin came to Tennessee in 1800, slavery in Western Tennessee had been on the decline; slaves accounted for less than 10 percent of the state’s population. This new, faster way to gin cotton encouraged farmers to plant more crops, for which they needed more slaves. In a few short years, slaves made up 25 percent of the population. Their labor became a required element to a successful life on the prairie. Without a competitive cotton or tobacco crop, a family would not have been fed and clothed. The chance of failure—a constant threat in this fledgling country—would have grown immensely.

The first abolitionist newspaper in the United States, the The Emancipator , was published in 1820 by Elihu Embree of Jonesboro, Tennessee. Shortly after, another abolitionist newspaper had a brief run in the area. Eastern Tennessee was a hotbed of abolitionist opinions, and voted to remain in the Union. Still, Western Tennessee’s reliance on slave labor created a staunch opposition, and both pro- and anti-slavery adherents argued their points of view at constitutional conventions. Both abolitionist papers failed, due not only to a lack of support, but vehement disagreement in the views they published. As these battles ebbed and flowed, it became more difficult to disengage from the practice of slavery in the areas of the state which relied on it to produce its cotton. As the slave population grew, white fears of slave revolts deepened.

Soon after Peter’s death, the lives of his slaves changed drastically. Slaves were no longer allowed to carry weapons of any kind, unless they were the designated hunter for their plantation, and carried the necessary papers to prove it. Codes were enforced which required slaves to carry passes, restricted them from owning property, and from buying or selling anything without their master’s written approval.

A law was passed prohibiting any person, white or black, from saying anything “calculated to induce insurrection or insubordination to proper authority,” including any and all discussion of abolition.

To prevent the possibility of a population of freed slaves—whose movements and speech could not be controlled—masters were no longer legally allowed to grant emancipation. Eventually, they could petition a court to emancipate a slave from their ownership, but the court had the right to deny the petition.

If emancipated, a slave was expected to leave the state, to make a home in what lay beyond. Even those who denounced slavery wanted all black people removed from the state, lest—as an article in the Knoxville Register put it—Tennessee was to become “a receptacle of the vicious and desperate slave as well as the depraved and corrupting free man of color.”

What lay beyond could be yet another state with even more impossible laws for former slaves, more restrictions on property, speech, and movement, more fears and hostilities toward free black people. They may be re-sold into slavery, an illegal—but common—practice.

In 1834, a report by a committee of members from each congressional district in Tennessee argued that slavery was an evil, one which should not continue, but due to the burden of laws that had piled up over time and had been placed on the freed slave, he was far better off remaining enslaved, under the protection of his master.

Protection means to care, to shield. It is a place of sustenance, of comfort. It is something that my grandfather’s slaves could not offer their children. From the moment of their births, they became property, as did entire generations of slave children. Peter’s slave Fanny brought her babies into this world, loved them, nurtured them, taught them how to speak, when, and to whom. She taught her children the dangers of the world, its dark corners and white machinery, its many sets of rules that changed with the wind. Fanny, like the slave mothers before and after, protected her children, all the while knowing that a day could come when they would be placed on an auction block and sold into the unknown. She, the mother, bore the unfathomable duty of safeguarding her children, only to be forced to release them into the wide open mouth of America, never to be seen again.

In 1807, the Atlantic slave trade was prohibited. With new limitations on the slave supply, and the increase in cotton production, there was now only one way to increase the slave population and keep the South lucrative. Slave masters forced male and female slaves to share living quarters, coercing sexual relations on threat of punishment or death. Slave narratives of the time reflect the constant buying and selling of female slaves, an endless rotation of sexual partners forced upon the strongest male slaves. Their only purpose was to create more slaves. Failing to become pregnant placed them back on the auction block, where they were marketed for the same purpose, again and again. These same women were also expected to succumb to the sexual advances of their masters, bear their children, and release those children to the auction block, again and again. The slave woman’s loss of sexual agency did not begin with the close of the Atlantic slave trade. The use of her body for its ability to produce more slaves, however, became another abominable, everyday part of a slave woman’s life after 1807. It was but one more marker on the road to the end of personhood, and the beginning of thinghood.

Black women, with their intimate knowledge of what awaited their children, survived pain and terror that most of us cannot imagine. Peter’s will makes no mention of fathers, of husbands, of relationships of any kind between his slaves, which begs the question: Who fathered Fanny’s children? Were they the product of rapes, of forced sexual encounters with Peter’s male slaves, with Peter himself, or with his sons? We know of at least two of Fanny’s children: the two mentioned in the will. How many more were there? How many were daughters? How many little girls was Fanny forced to hand over to a world of horrors she knew too well and could not change? How many of her little girls, who she knew so secretly and surely among the muffled shouts and screams of her beating heart to be people , was she forced to watch the world turn into things ?

Perhaps Fanny and slave women like her were told that their children were bought by good masters, that they would be protected. What did this word mean to them, they who knew the reality of it, who felt the sharpness of its edges, who paid a higher price than most for the growth of America? Surely when we say that life with a kind master was safe, when we say that slavery offered protection from the dangers of the seventeenth-century American landscape, we mean something else. The protection of a slave was the protection of an asset.

Hall was another one of my grandfather ’ s slaves. He was willed to my seventh great-grandmother, Mary, to be sold in the event of her death or remarriage, and the proceeds from his sale were to be divided among Peter’s children. In 1810, Hall paid the Cocke family a sum of five hundred dollars through a lawyer, with the intention of buying his freedom. Whatever dangers awaited him outside of Tennessee, outside of slavery, Hall wanted out.

My grandfather’s sons, Stephen and Abraham, executors of his will, acknowledged the payment, and agreed to free Hall when Tennessee’s laws permitted them to do so.

In 1815, Hall appears one last time, in the list of property in Abraham’s will. He stands, “Negro man Hall,” among the cattle, the sheep, the candlesticks.

Slavery ended in Tennessee fifty years later.

Two Halves

The Germans have a term, vergangenheitsbewältigung , which means “coming to terms with the past.” In the years after the atrocities of World War II, the living moved on, attempting to rebuild some kind of life between the wounds left in society. Everyone knew what their neighbors had done, and what they had not done. For a generation, a culture of silence was adopted. Former Nazi commandants lived under assumed names. Discussing war crimes was considered gauche and impolite. Children were slapped for asking what their fathers did during the war, discouraging them from asking again. But it is this next generation that continued to ask, that refused to stay silent on the matter of the destruction of so many lives. The children of war criminals began to face the realities, to visit the sites of their parents’ crimes, apologize to victims, move beyond guilt and into a shared responsibility for healing.

Has there been an American generation of vergangenheitsbewältigung yet?

I can’t pinpoint a time from my own childhood when we did not skim the passages of slavery, look at it through the lens of necessity, justify its reasons and its duration, focus on the fantasy of the kind white master. I can’t think of a time when there hasn’t been at least one voice extolling the virtues of the South, its ability to overcome and rise, at least one voice claiming that the slaves were freed, and life got better. I view this refusal to see the facts and laugh long and loud, I roll my eyes, I don’t live there anymore, I’ve moved on, and I can see it clearly from on high. But even now, I want to find some excusable reason, something that forgives every rung of the ladder my ancestors built to climb higher through history.

If not for the destruction of black families, of generations of black ancestry, my family may have failed to make a life for themselves. They may have fallen into poverty, disappeared from the record books, as the sheep and the candlesticks were sold for food. Their prominence in a young, embroiled America, the evidence of their lives, was due in large part to their willingness to enslave others—to consider other human beings as their property.

Consider Hall exiting slavery in 1865, without a single possession, without money or clothing, crossing the border of Tennessee and into Kentucky, hiding in the woods. How will he navigate the laws which dictate where he can live? Will his children go to school with white children, and which water fountain will they drink from? Will he be forced to leave his home in the night, under the glow of a burning cross? Will he be shot by a police officer?

Slavery died, and America’s problem with race continued to grow strong and healthy, a poisoned vine reaching for the sun. It’s the reason a black child can’t play with a toy gun in the park; it’s the reason a black man with his hands in the air is still a menace, a depraved and corrupting man of color . It’s the reason black mothers still bear a burden of fear that white mothers do not: Will this be the day that their children don’t come home? Will their children—vessels of blood and historical trauma— be the next examples of destroyed black lives?

The culture of silence, of condoning, of insisting that this shouldn’t be a problem, that we’re not offending anyone, has persisted for a disgraceful amount of time. How can the descendants of slave owners move on from that shame if we only replace it with another?

The avoidance of shame, when it is yours to bear, will drive you underground. It will rot the beams of your home, spread its decay through your small towns, reduce the world around you to a husk. It will keep you silent and smoldering, gathering in the dark with those who are most like you, where you can finally say to one another all the words you know to be the weapons of your father, and his father before him. It spreads, infects the hearts and minds of those watching from the congregation, from the benches and the bleachers.

It is terrifying to peer into the pools of history, where our deeds have washed up onto the shore and lay transparent with the truth of what we have done. It is even more terrifying to consider that we have learned nothing, that we are exactly the same as we were in the days when we made the choices that both built us and broke us.

Acknowledging the evidence in my seventh great-grandfather’s will means that I have stumbled upon a very old, and very deep pit of reckoning for my family’s role in the oppression of black people. It is like waking up one day to find that you personally owe a great debt that can never be repaid. Two halves of myself argue about this: I did not choose the life I have, but I have reaped its benefits. I did not enslave anyone, but am I a part of something that continues to allow these terrible things to happen? In the end, there is no answer, just a place of soreness and discomfort in the middle, a chasm of nothing but shouts and echoes.

The world is full of people whose ancestors thrived and depended on slavery for their quality of life. Do we all have these two opposing sides within us? Maybe some of us are choosing to face just one absolute, the one that allows us to be free of our debt, which allows us to refuse to accept the wounds for which we are responsible. Maybe it is on this side that we are reimagining slavery, where we create the packaging of protection and necessity and kindness to cover it. Maybe it is only when we step into the other side, acknowledging both our benefits and our responsibility, that we will begin to find the road through our guilt. Only then when we will survive on the fires of a shame that does not consume us, does not bury us under its ashes, but ignites us, propels us forward to a future that is unrecognizable from our past. Only then can we shed our shame, when we can finally bring it out and let it burn.

I want to start the long walk down this road, carrying with me the deeds of my ancestors. I want to ask the questions that lead to more questions, I want to open all of the doors, and all of the doors behind them. I want to stop swimming through the dark water and sink, all the way down, until I know what’s been hidden there.

But this is not about what I want. This is not about what I need.

It’s about hearing the voices of slavery, which are speaking still, speaking loud with the throat of hundreds of years. Even now, as America insists that the black bodies on the ground deserve to be destroyed, trampled, forgotten—for the sake and safety of the rest of us—even now, black voices are telling us what we have done, they are showing us the depth of our illness, they are asking us to build a bridge across our fear. They are asking us to dismantle the scaffolding of racism that surrounds this country still, they are asking us to stand next to them, and in front of them, when needed, at rallies and demonstrations where police still brutalize and dehumanize them. For what my grandfather did to contribute to this structure, I will show up, I will add my name to the list, I will stand where I am needed and do all I can to help tear it down.