People On Writing Bodies

As a Disabled Writer, I Know My Stories Are Worth Telling

These worlds I dearly love, with science-fiction that supersedes the science in our reality, deserve Smart Drives and automatic doors and disabled heroes, too.

I am staring at a blank page. My fingertips are poised above the keyboard, but the metronome blink of the cursor is mocking me. The words that used to pour out of me has been dammed. I feel parched without them, begging for a flood of prose.

My words disappeared, not at an exact moment, but slowly, across the arc of my late twenties. At twenty-six, a geneticist finally told me that hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) is the reason my joints have been unexpectedly dislocating for years. The good news: I was not a hypochondriac exaggerating my symptoms to score pain medication. The bad news: My body makes collagen incorrectly at a genetic level, which means my body is forever altered by misfiring DNA that can’t be fixed.

Symptoms that have plagued me for years were explained by this diagnosis, but it did not come without consequence. The mortuary, where I worked, balked at my disease and the time it takes to be sick. They limited my hours until my meager paycheck made paying rent impossible, much less the newly copious medical bills. Abandoning the humdrum 9-to-5 of death—knowing how easy it is to exit this world and how much more fragile my own body is compared to others—sent me spiraling into traumatic PTSD.

I’d spend hours frozen in bed, listening to the galloping thump of my heartbeat, terrified that my aorta was tearing itself apart in an aneurysm, one possible complication of hEDS.

I would press my fingertips to the cleft of my jaw and throat, counting my heartbeat and willing it to slow. I’d flick on the lights, pushing on my thumbnail to watch the action of capillary refill turn the nail white, then back to pink—proof that I’m not bleeding out.

I began to see therapists who told me to practice mindful breathing, to distract myself from my fear by describing my surroundings in great detail. Surgeries piled up—on my dislocated jaw, out for so long that I survive on smoothies for four months; my dislocated big toe, jutting out at an angle that makes wearing shoes impossible; my uterus, riddled with cysts and blocked with nonmalignant tumors.

In the operating room, I’d reassure myself that if I died during anesthesia, I won’t be awake to feel any pain. Medications became the final nail in the coffin, and between the terror, anxiety, and unbridled pain, I was—am—exhausted.

And wordless.

It feels like exile for someone who has always written, ever since I was first able to put pencil to paper. I was raised on bedtime tales and a well-used library card. Nowadays, I never go anywhere without a journal and a pen, a habit so old that I forget its inception. When not writing, I devour books. My ears bruise from wearing headphones to absorb audiobooks if I can’t have my nose buried between actual pages.

My favorites are often science fiction: set in the future, with technology that doesn’t yet exist, and a spaceship or time travel. My softcover copy of Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, my very favorite book, is like a well-worn security blanket, offering solace within its dog-eared pages.

Words are a precious currency, the way in which I make sense of the world. I can’t remember a time before I lost my words, and yet here we are. Staring, again, at a cursor that flashes in an infuriating rhythm on the desert of the blank screen.

Words are a precious currency, the way in which I make sense of the world. My writer’s block lasts for more than two excruciating years. I curl up with other people’s words instead. I trawl through books, blog posts, and Twitter threads about writing. I treat it like an equation that can be solved—if only I could find the right formula.

My disease is degenerative and those two years wreak havoc on my body. I spend nights curled in bed, nursing heating pads and lidocaine patches as I return to the books that feel like home, trying to figure out why they work so well. I brace dislocated bones with pillows as I try to parse out perfect plots. I pull out Fahrenheit 451 , fanning the pages beneath my nose to inhale the papery smell of secondhand bookstores. Stories bring me comfort as I heal from surgeries and procedures. They are loved, re-read, and uplifted until they’ve reached near-mythical status.

The unpredictable changes in my body eventually necessitate a big shift: I begin using a wheelchair part-time, to avoid hip dislocations and episodes of syncope—fainting—when standing. Using my wheelchair in public makes me realize that the world remains deeply inaccessible, despite civil rights laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The number of times I encounter blatant discrimination becomes uncountable. Doors without automatic openers stop me cold, staircases abound, broken elevators confound, and the accessible entrances are inevitably around the back of the building, usually near the dumpsters. Because my wheelchair is manually controlled by my hands on the handrims, I can’t use it if my wrists, elbows, or shoulders are dislocated. But when I can use it, I do.

A paradigm shift follows, because it is impossible to rely on an accessible device and think of myself as non-disabled. The disability community online is vast and diverse, and the way they think about being disabled opposes society’s typical ignorance and mockery. To them, disability is not just a body’s state of being, but an identity that fundamentally changes the way they—we—interact with the world.

With this comes the realization that illustrations of disability are invisible in our society. Disabled heroes do not save the day; we are saved by nondisabled champions. Wheelchair users are not leads in the stories I’ve grown up devouring; if we exist at all, we are one-dimensional foils, or killed off so the nondisabled main character can learn a saccharine lesson.

I begin tweeting about my experiences with ableism and inaccessibility. The character limit makes each tweet feel less like the impossible task of writing and more like an amiable conversation with faraway friends. Before I know it, an editor reaches out, linking back to one of my threads.

“Hi, Ace! I wanted to see if you’d like to expand on these tweets in a paid op/ed.”

I reply quickly. Yes!

The words do come, but in a steady stream instead of a flood. Seeing my name attached to a byline gives me a heady thrill. I can still write. I make a pledge to ensure that I’m published somewhere at least once a month. I force myself to pitch stories, even as I second-guess my ability to string sentences together. More bylines follow, each new article added to my growing resumé, proof I could write, proof I was worth listening to.

Seeing my name attached to a byline gives me a heady thrill. I can still write. Then a call for pitches about sci-fi road trips catches my eye. Fahrenheit 451 is sitting on my desk. I remember reading years ago that Ray Bradbury donated some of his papers to a university, one just far away enough to feel like a tease.

Was it SoCal, or up north? Did I imagine that? My search results verify that he did donate his papers to the University Archives and Special Collections at the University of California, Fullerton.

I compose an email to the editor: “With the 2018 movie rendition of the novel, I think it would be extraordinarily cool to make a road trip down south to check out the collection.” With his blessing to ask for an appointment, my heart hammers as I write to the head librarian, asking if a freelancer might have access to the collection and whether I can schedule a visit. Soon.

Patricia Prestinary, the librarian and archivist for Fullerton’s Special Collections, asks about me over the phone with a level of circumspection, her voice guarded. I am too excited to maintain a modicum of professional composure, nearly giddy as I explain my love for the novel. I have a tattoo on my hip based off of my favorite line in the book, I explain to her. It would be overwhelming to see the papers in person.

She says she needs to run it by the dean, cautious as we sign off. She has warmed to me by the end of our talk, perhaps recognizing that I am a dyed-in-the-wool fan of the highest order and not just someone trying to appease an editor. They’ve only worked with the local paper before, she says, never any outside reporters.

I email my editor (who doesn’t reply), then research flights and the cost of accessible hotel rooms. Patricia tells me the dean has approved my visit. The fall semester is starting soon, so she suggests we schedule within the next week. I am so busy punching the air in excitement that I have to compose the letter to my editor with one hand.

But still, he doesn’t reply.

Days go by.

Just circling around again , I write, only because I need to confirm with the librarian . I try not to give away how desperate I am to do the story. I’m cool, I try to say through my tone. We’re cool. I’m definitely not freaking out about missing out on the experience of a lifetime.

He finally answers— Let’s do it! he writes—but when I ask about what the magazine can help me pay for in terms of travel and lodging, he stalls. “I hadn’t thought about that aspect,” he hedges. “Is there a way to write about it from afar?”

“I potentially have people I could crash with, but I need a little something to work with!” I answer.

But he doesn’t reply.

Days go by.

“The editor ghosted me,” I tell Derek, my fiancé, refreshing my email. “I’ve got this appointment, but I don’t know if I can handle my wheelchair and my luggage alone.” I’m trying not to take it personally, but I feel limp and listless. If I’m not even worth an email back, my story must be worth even less.

Derek plants a kiss on top of my head. “Don’t cancel your plans yet,” he cautions. “You never know what might happen.”

Two days before my library appointment, my Smart Drive arrives. It’s an expensive motor that attaches to the back of my manual wheelchair, turning it into a hybrid electric chair that requires far less physical effort to maneuver. I’ve been navigating insurance bureaucracy for months so I don’t have to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket. The woman who installs it wears towering heels and speaks in a lilting Eastern European accent. She says yes when I ask if we can practice in the parking lot.

Outside my tiny apartment, my wheelchair jostles over the uneven asphalt. I use a smartwatch to make the Smart Drive move. I tap it twice against the handrim to zoom forward; one tap stops the acceleration, but maintains momentum, like cruise control. I cannot contain my uncontrollable laughter, which echoes through the fog. I am in control of my own private spaceship, faster than a shooting star. The Smart Drive is the epitome of science fiction, except it exists behind me in real life.

I crow to Derek later, “I’m going on this trip!” I know the journey will be a story to tell eventually; I’ll figure everything else out later. But right now, the Smart Drive is the science I needed to get closer to my books, my words, and my Holy Grail of science fiction. So fuck it, I say. I buy my tickets, reserve an accessible room, and pack my bags. I’m going to UC Fullerton.

*

Travel is easier than it’s ever been with the Smart Drive attached to my wheelchair, but still not perfect. Trying to maneuver with one hand while directing my suitcase with the other is nearly impossible. The TSA agents and airport employees express surprise that I’m traveling alone, without a carer. The mandatory security pat-down is humiliating. I tweet a picture of my wheelchair on the jetbridge, hoping no one damages her. The door to my hotel room doesn’t have a working automatic opener, so I have to hold it open with my foot as I wheel in, hoping I don’t dislocate anything.

I feel like I’ve been hit by several cars when I wake, but I slip into a navy blue dress spangled with stars and call a car for the drive. The campus seems much bigger than the tiny map I have pulled up on my phone from the parking lot. As I navigate, shaded from the sun by towering palm trees, I am so glad for the miniature jetpack attached to my wheelchair.

In the white light of the August heat, the unique design of the Pollak Library outshines most of the other stolid buildings on campus. The outside of the building is peppered with linking three-dimensional hexagons. I visit the bathrooms first, marveling at the accessibility of the gigantic stalls and ceiling to wall doors. I turn my wheelchair in a full circle without hitting anything.

Photograph by Ace Tilton Ratcliff

As I ride the elevator upstairs, my heart flutters. I follow a benign academic hallway of white walls and fluorescent lights until I reach a two-shelf display of sci-fi books, protected by sheet glass. A plain white sign declares, “UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS” in all caps. A smaller sign admonishes “No Food or Drink” in red.

I push open the heavy door and into a small room with two long tables, chairs parked on each side. Directly ahead, Patricia’s office is on the left, and Nick Seider, the archives assistant, has an office on the right. Behind me, antiquated oak library card filing cabinets, their labels handwritten, line the walls. Patricia and Nick have been waiting for me here. I introduce myself, trying desperately to contain my excitement. Patricia has dark hair and a lithe, slender athleticism. Nick is tall and effervescent. Both of them have kind smiles, and neither express surprise at my wheelchair.

Patricia guides me past a parked library cart and into the stacks. The shelves stretch back for ages. The space between most of them is too narrow for the width of my tiny chair. They are lined with books and labeled archival storage boxes.

Within the stacks is a trove of artifacts that once belonged to my favorite science fiction writers. There are pages of handwritten first drafts and notes from Frank Herbert as he created the universe that housed Dune and its subsequent sequels. I leaf through decades of Philip K. Dick’s private correspondence, including a waterlogged letter from Doubleday & Company that decided on Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? as the final title for that particular novel. There are so many rejection letters and fanzine criticisms of his work.

Eventually, though I am nearly overwhelmed by the treasures already encountered, they pull out the Bradbury papers for me.

I sit for a moment, trying to compose myself. I wear blue gloves to protect the pages. Nick and Patricia return to their offices. I cannot believe they trust me to rifle through these precious papers. My eyes well with tears. It feels like confronting sacred texts after years spent studying them as a novice.

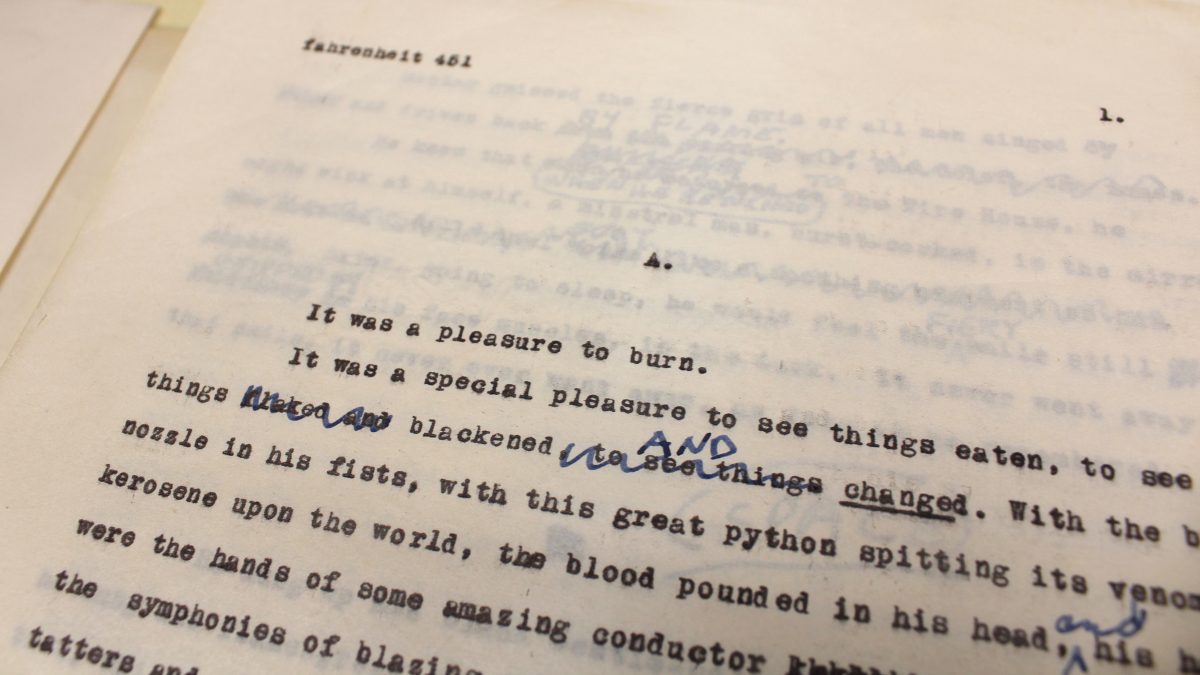

The history of Fahrenheit 451 is separated into manila file folders, each one holding a step of evolution describing the changing nature of the work. The novel began its life as a short story called “The Fireman,” and I comb through tissue-thin paper to read from the first draft, then the second. Therein is the skeleton of what would become a book, drafts of sentences that eventually grow into full paragraphs. I watch it shifting as it’s shaped, the typed lines wobbling like a toddler testing its first steps.

The renowned first line of the novel—“It was a pleasure to burn.”—stands starkly on the discolored first page of its second revision. Like me, Bradbury corrected his pages with a fountain pen that bleeds thickly. He crosses out phrases, draws lines through entire paragraphs, covers the margins and blank space with barely legible notes punctuated with exclamation points. Some pages are entirely discarded, scribbled with x’s and arrows or blacked out with a repetitive kkkkkkkkkkkkk.

His notes are scratched on yellow notebook paper, reflecting jettisoned dialogue, barely legible reminders to himself, newspaper clippings that helped shape the outline of this world. A doodle of a cartoon figure with a triangle body and stick arms appears repeatedly in the margins.

There is a formidable silence in the room, interrupted only by me turning pages. The longer I sit, reading, the more the veneer of holiness disappears. I begin to recognize that Ray Bradbury’s celebrated masterpiece did not begin as a flawless work. Bradbury, it seems, was no more capable of churning out something impeccable on his first try than Herbert or Dick were. These gods of the science fiction pantheon, perpetually put on reading lists and uplifted as the founders of the craft, are regular humans.

Photograph by Ace Tilton Ratcliff

Like me, they scrabbled to meet deadlines and relied upon editors to help shape their first drafts into recognizable form. They were hampered by thoughts of inadequacy and scrambled paycheck to paycheck trying to make a living from their words.

I stay in the reading room until it’s past time for Patricia to lock up. I’m filled with gratitude as she returns the materials to the shelf and flicks off the lights. I glide out into the sultry heat of the California sunshine on my rocketship wheelchair.

Back at the hotel, I sit at the desk and words pour out of me. I fill a small journal, my fountain pen moving so quickly that the ink is still wet when I turn the pages. My dislocated fingers can barely keep up. Being able to focus on the inarguable imperfection of my favorite writer has dislodged an obstruction of self-doubt and uncertainty. At home, over days and weeks and months, the words still stream forth: story ideas, pitches, submissions to retreats, a novel outline. The solution for my writer’s block is the act of writing itself—and writing myself.

The disability community has a motto: Nihil de nobis, sine nobis —nothing about us without us. There will never be disabled leads unless disabled writers create worlds with them. My stories are worth telling. Like its authors, science fiction in its current incarnation isn’t absolute, either. It is borne of a time steeped in misogyny and sexism, with a dash of ableism. Just because it exists in a form where disabled characters aren’t the lead doesn’t mean it can’t be improved. These fictional worlds I dearly love, brimming with science that supersedes the science which exists in our reality, deserve Smart Drives and automatic doors and disabled heroes, too.

My fingertips fly across the keyboard as I compose an email to a new editor.

“My name is Ace and I’m a freelance writer . . . ” I begin. “This summer, I took myself on an adventure to a massive collection of science fiction and fantasy goodies at the Pollack Library at CSU Fullerton. I took myself on a trip specifically because I wanted to see Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 from start to finish . . . ”

The cursor blasts off the page, launching my words into unfettered freedom. The dam has broken.