People My Life in Sea Creatures

A Queer Love Story at the Bottom of the Sea

What the Venus flower basket and a Norwegian bildungsroman can teach us about queer adolescence.

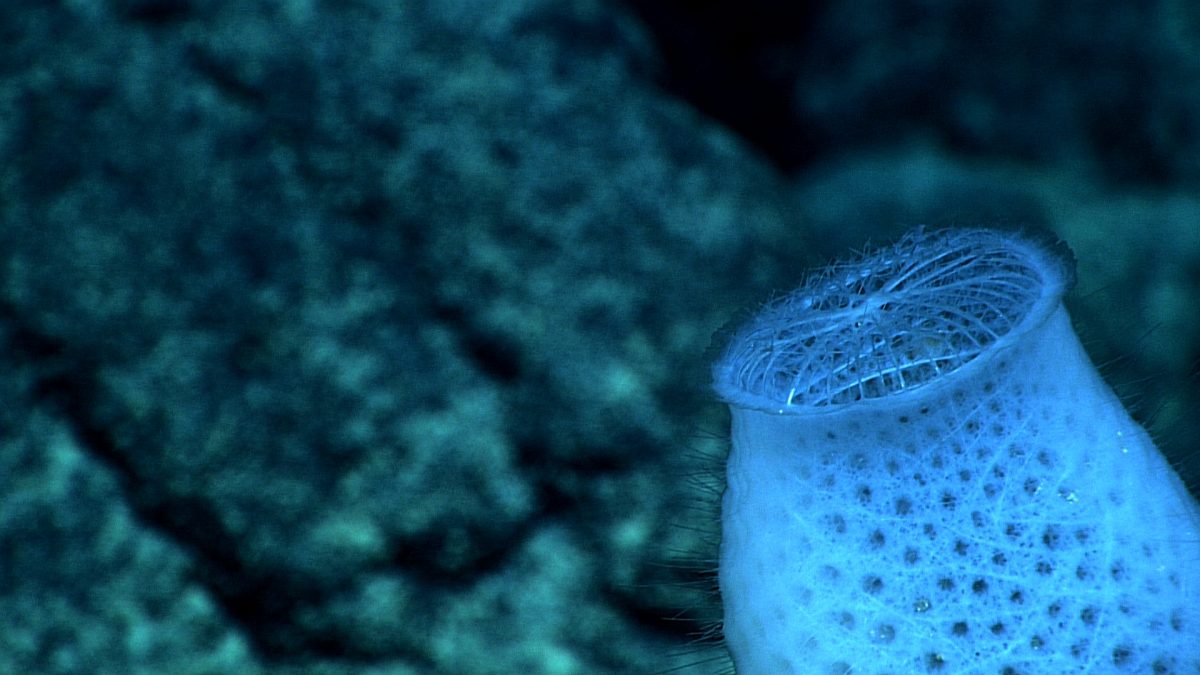

There is a classic love story you might have heard of, trapped in glass sponge at the bottom of the sea. Glass sponges earn their name from their peculiar skeletons , crystalline lattices of tiny rods of silica. At a distance, this specific species of glass sponge looks like a glass-blown morel mushroom, or the turret of a cathedral made of ice. Despite the suggestion of their common name—Venus flower basket—these sponges don’t care much for love. Like all other sponges, they have no brains. But they play host to one of the ocean’s most unknowingly romantic invertebrates, the spongicolid shrimp.

Not quite a true shrimp and not quite a prawn, the spongicolid shrimp belong somewhere in an interstitial taxonomy. These tiny creatures live out their entire lives inside the honeycombed walls of the Venus flower basket. Baby shrimp, drifting powerlessly throughout the deep sea and small enough to slip in through the sponge’s porous walls, enter the baskets in mated pairs. Over time, they grow within the walls of the sponge. Soon, they grow too large to escape its walls. The deep sea is dangerous, and Venus flower baskets offer protection from whatever lurks in the benthic shadows. Over time, they reproduce, sending their tiny offspring through the membrane of their glass house so that they may find new sponges of their own.

It’s a suffocating metaphor—a lifelong commitment to one other being that relies on a kind of prison. But in a world whose denizens reproduce by flooding the waters with sperm and eggs and hoping for fortunate collisions, you have to admit that even an imprisoned monogamy doesn’t sound too bad.

As such, the Venus flower basket has unknowingly become a symbol for marriage, love that’s meant to last until death. In Japan, people often give the skeletons of these sponges to couples on their wedding day as a symbol of their commitment to each other unto death. They call one species of glass sponge Kairou-Douketsu, which translates to “together for eternity.” If you’re attending a wedding anytime soon and don’t buy into registries, a ten-inch Venus flower basket will run you around seventeen dollars on eBay, shipping not included.

*

At a glance, Norway appears to be the terrestrial world’s best bet at mimicking the deep. It’s a land defined by its proximity to the sea, one long scabby, splintered coastline nearly swallowed by the Arctic Ocean. It’s harsh, frigid, and, between October and March, beautiful, with the slithering, lime-colored streaks of the Aurora Borealis—the closest the sky has ever come to bioluminescence.

Tarjei Vesaas, who died in Oslo in 1970 at the age of seventy-two, was widely recognized as one of Norway’s greatest writers, which is to say I had never heard his name until a comparative literature course in college. His best-known work, a sliver of a novel called The Ice Palace, concerns a powerful, binding intimacy between two eleven-year-old girls, Siss and Unn.

Siss, loud and vivacious, and Unn, orphaned and melancholy, become fast friends until Unn skips school to explore what the village calls the ice palace—an accidental structure created by the drippings of a nearby waterfall over a long, cold winter. She enters, wanders, gets lost, and finally, unable to find an opening large enough for her escape, freezes to death. Trapped within the palace, her cold, hard body becomes a fixture in one of its translucent rooms. Days later, as adult rescuers seek to find her, they cannot squeeze through the same fissures that Unn, a child, could so easily trespass.

The shrimp, too, can only enter the latticed pores of the Venus Flower Basket as larvae. Microscopic bodies have no problem slipping into small spaces. As larva, the shrimps have no sexual dimorphism and do not care to know the other’s sex. In this neutral state of youth, they try out a variety of sponges, passing in and out of the doily walls of one flower basket and another.

They live in all kinds of families. Sometimes, ten young shrimp squeeze into the same sponge. Other times it’s only two. Scientists have observed that young male shrimps tend to leave the nest earlier, maturing in the cold black ocean until they’re ready to mate. But young female shrimp are much more likely to live in groups, or pairs, taking comfort in this community.

Like most other sponges, the Venus flower basket is hermaphroditic and contains both sexes simultaneously. For larval shrimp, it’s a queer kind of shelter. I see their adolescence as a kind of experimentation in chosen family, trying out different sponges, lives, and crustacean partners. Like me, they understand growing up is always easier with a bud.

*

In The Ice Palace, Siss and Unn share a kind of intimacy that male scholars of the time insisted could not possibly be queer, as it would be low-brow or even perverted to draw such a conclusion from the text. These men of status insinuated that to include such content would constitute pornography—no, they argue, Siss and Unn are two innocents. It’s just one of those Elena Ferrante friendships, impossibly close yet devoid of any unacceptable, lesbian longing.

Still, the girls are drawn toward each other. Whenever they pass, they can’t help but look at the other in what Vesaas simply calls astonishment. Siss notices Unn, despite her pretense of indifference, and takes every opportunity to watch her in class. In turn, “Siss would notice the sweet tingling in her body: Unn is sitting looking at me.” I felt warmed by this urgent, unnameable feeling, recalling the time I dated a boy because I thought his sister was the most beautiful girl I had ever seen. A yearning both red-hot and wrong-feeling, one that astonished me when I first saw her.

One day, Unn invites Siss over to her house after school. Behind the locked doors of her room, Unn suggests the two undress. They do, and see that each glitters in the dark of the room. Unn tells Siss there is something she wants to tell her, something she has never told anyone before, but she can’t work up the courage. Silence takes over. Moments later, Unn confesses: “I’m not sure that I’ll go to heaven.” Reading this passage again, I think of the time my closest childhood friend asked me to meet by a eucalyptus tree between our houses, where she told me she knew she liked girls, that she had always known, and that she wanted me to know too. I think of my friends who are still closeted, many of whom come from religious backgrounds and have yet to come to peace with themselves, let alone tell their families.

In 1987, director Per Blom premiered a film version of The Ice Palace that made Unn’s longing for Siss explicit enough for the film to earn a spot on some list of the ten best Scandinavian LGBTQ+ films, starkly within the canon of movies where the lesbian dies. While all film adaptations take certain liberties of interpretation, I’m clearly not the only one who noticed Unn’s desire.

The following day, soaked in shame and desire, yet frightened of seeing Siss at school, Unn plays hooky, intent on seeing the ice palace. She will see it first, she decides, so that she can show it to Siss later on, as a gift. She runs toward the waterfall, in wonder and joy, so much joy, on the day she is to die.

*

While Venus Flower Baskets look like lace, their walls are startlingly rigid. Glass sponges are made of silica, the same material as a window pane or shot glass. But while we harvest silica from sand and quartz to make windows, glass sponges extract silica dissolved in the ocean water. The flower basket’s siliceous skeleton is made up of six-rayed spicules, pin-like windmills that weave together into an ultrafine, interlocking mesh. The skeleton itself is not the living sponge, but its scaffolding. Instead, the animal takes the form of a thin layer of cells that ensconce the skeleton. The end result is a sponge that looks so much like a building that scientists refer to the space inside its body as an atrium.

Though the ice palace traps Unn, killing her in the long run, she finds in it a measure of safety she has otherwise never known. Vesaas writes her slow freezing as sweet, almost revelatory. The soft plinks of melting ice sound to Unn like a song, the cold begins to feel comfortable, and the light blinds in a kind of absolution. Unn may not have entered the palace knowing she would die there, but her fate hardly comes as a shock.

If children like Unn can’t imagine a world where they can exist as they’d like, if they are taught that feelings of queerness are inappropriate at a young age, then they have no recourse to find a way to live with authenticity and without fear. A few years ago, home for Christmas break, I started seeing someone who had gone to high school with me. They had been out when I was not. When we told each other our coming out stories—casual first-date conversation in any queer relationship—I recounted my relatively easy coming out. They told me their much more difficult version. Moments later, as I took it all in, they added, “Because I never saw anyone like me who was old, I guess I always assumed I would die young. But I’m glad I’m still here.”

I brim with gratitude for my queer women role models, who entered my life as friends and teachers and lovers and showed me a way to carve out a life that felt good and true. On her way to the waterfall that fateful day, Unn realizes something: “All of a sudden she was no longer alone. She had found someone to whom she could tell everything, soon.”

The dominant narrative of the Venus flower basket is of heterosexual monogamy, of a male and female shrimp living together in a small glass cage until they die. I find this more stifling than romantic. But there are certain things these narratives leave out. What they don’t tell you in nature documentaries or magazines is that large female shrimp have the power to break the walls of the sponge, or that a broken sponge has the power to rebuild its walls. They don’t tell you that sometimes mature female shrimp live alone, and that that’s okay.

Scientists, in a recent survey of flower baskets collected off the shores of the city of Makurazaki, in southern Japan, found clusters of larval shrimp bobbing in the shared shelter of a sponge. They also found a number of shrimps living alone in baskets of their own, ghost-white claws pressed against the walls of the sponge like a girl who grew too cold to stand.