People Fifteen Minutes

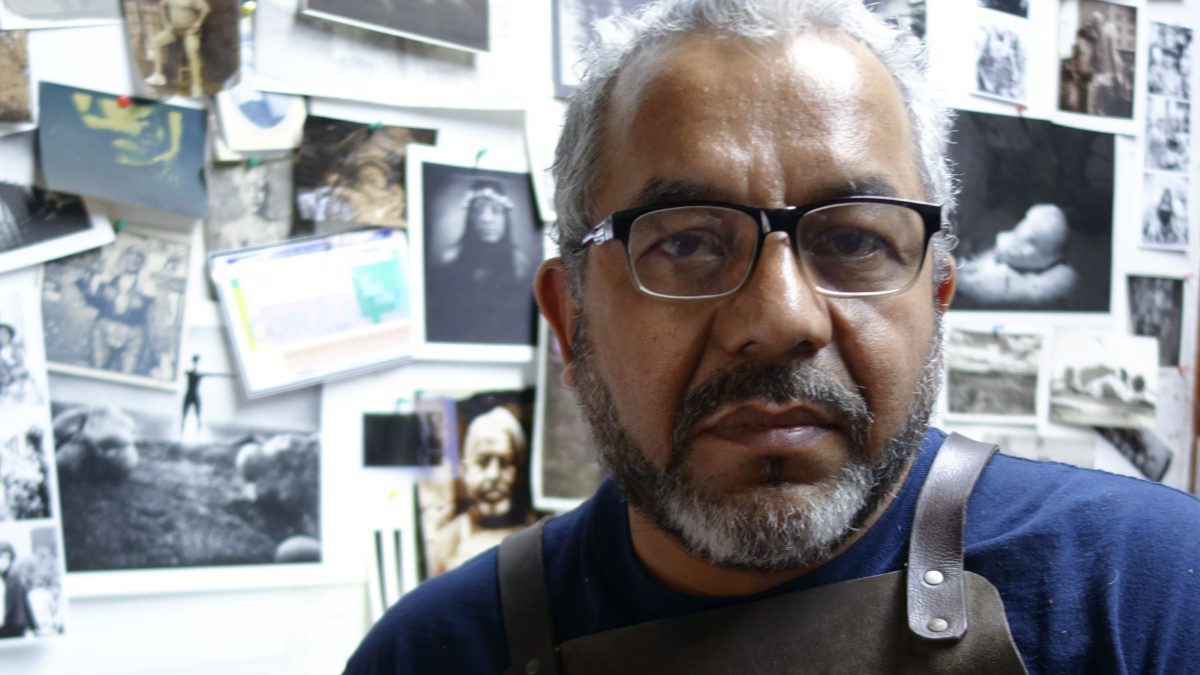

15 Minutes with Arturo Talavera, Mexico City’s Photography Master

Arturo is a modern-day alchemist, creating beauty out of bending light, and capturing photons on glass, silver plates, and egg whites.

Arturo Talavera arrives early in the morning to his photographic studio in the historic center of Mexico City. The studio is situated in a two-story alcove on the backside of a monstrous grade school, in a now sagging building originally built in the eighteenth-century to educate orphan girls and widows. The school continues to operate, but these days is secular and coeducational, a bit like the historic photographic processes Arturo works to revive, preserve, and adapt to modern times.

Today, Arturo is in his studio, the Taller Panóptico, refining one of twenty alternative photographic processes he has meticulously taught himself over the past few decades. Arturo is fluent in the earliest forms, such as daguerreotype and wet plate collodion, taken on metal and glass plates, as well as newer techniques that blend digital methods with analog approaches, like carbon printing, platinum palladium, and the breathtaking bright blue cyanotype. As I walk into the studio, Arturo is making a set of ambrotypes on glass for another artist’s upcoming gallery show in Mexico City. He’s the only one in the whole city who can be trusted to do it right.

Photograph by Arturo Talavera, courtesy of the author

Before he dove into antique photo processes, he was a freelance photojournalist in the eighties and nineties, working in the state of Veracruz. Even as a professional photographer, he’d always dabbled in alternative styles in his free time and taught printing classes at the Veracruz cultural center. One day, he decided he’d had enough of the unpredictable hours of freelance life. It was time to focus on what he really loved: making art.

Nowadays, he spends his mornings poring over original nineteenth-century texts, mining them for the only instructions that still exist for practicing dormant photographic arts. Such techniques include albumen printing, which is done from direct contact of the negative onto sensitized paper prepared with egg whites—hence the name of the process, albumen . I like to think of Arturo as a modern day alchemist, traveling back in time to create beauty out of bending light and capturing photons on glass, silver plates, and every imaginable kind of paper, even egg whites.

Time. It is the constant that dominates the relationship Arturo and I have as teacher and student. While Arturo knew from an early age that he loved photography and visual arts, my own artistic urges lay dormant for most of my life. I chose, instead, to build my career as an academic librarian and professional archivist. But, as things seem to happen as they always should, it was my very job that brought me to Arturo’s doorstep.

In 2015, I decided to go to Mexico, leave my ten-year stagnant marriage, and take some risks. I arrived in Mexico City on a Fulbright grant for what was originally to be a nine-month research sabbatical. While I was doing work at the national photography museum, a chance meeting with the darkroom technician there had me instantly hooked on analog photographic processes. I listened, enthralled, as he explained the process of printing negatives for an upcoming exhibit on Nacho López, the famed Mexican street photographer and filmmaker.

I asked the technician where I could learn how to do the things he was doing. He gave me the address and contact information of a curious little workshop that gave classes in all order of old photographic methods. Just my luck: It was in Mexico City, called the Taller Panóptico, and run by a man named Arturo Talavera.

Although I’ve always worked in archives and I had come across a lot of beautiful old images, I never saw myself as someone who could be a creator of them. I never thought I had it in me to be the scribe who writes their stories with light, through the lens and onto the film, a photographer. I was just there to take care of other people’s art, make sure it could be looked at, and enjoyed for a long time. I really believed it was my duty to leave it to the artists to actually create the stuff, and to the scholars and art historians to talk about it. I was the invisible intermediary between creation and interpretation. In those days I didn’t necessarily see the problem with it.

But then I saw the darkroom technician printing sixty- and seventy-year-old negatives, literally reviving the past. Here he was, the intermediary no longer invisible, leaving his own fingerprints on the art. I knew it was time to step out of my own shadows, to assume the perils, risks, and rewards of the creativity I had bottled up after a lifetime of trying to hide it.

Photograph by Natalie Baur

The next week, I signed up for my first workshop at the Taller Panóptico. Our first lesson was the daguerreotype, the very first photography process invented in the 1830s by Frenchman Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre. I wanted to start at the very beginning of photographic time. I didn’t know what to expect going into the course, and I was struck at first by how simplistic and banal creating something beautiful can actually be. Along with my one classmate, we spent hours and hours in silence using power tools to buff brass plates coated with a thin layer of silver.

At the beginning, every five minutes or so, I would run over to Arturo to ask if the plate was smooth and shiny enough to capture an image. With his saint-like patience, he would tell me that it still needed much more buffing. After two days of buffing and much longer intervals between asking versions of “are we there yet?” we had the plates ready to start taking photos. Because the image that would be struck onto the sensitized plate is permanent, Arturo explained, we would only have one shot at getting an image.

I turned pale. No do-overs. I began doubting all over again if I had it in me to undergo this magnitude of the potential to fail. “Better to be safe as the invisible art handler,” I muttered under my breath. Arturo, in his tell-it-like-it-is way, told me not to sweat it. The only way to see how things work, he told me, was by trying, and by failing. A lot.

I wanted to be good at making art with old photographic processes, and I wanted to be good, fast—I was used to climbing ladders quickly. Arturo never scolded me for it, but he has taught me that time, slowness, trial and error, and above all, persistence are the real ingredients one needs to unlock the magical formulas key to the creative process.

In that first workshop, I spent days painstakingly preparing my plates and buffing them out. After all that work, to my horror, I often ended up with an underexposed, barely visible image. In some cases, I forgot to open the camera’s shutter and didn’t get any image at all. There is no beginner’s luck in analog photography. I realized with disappointment I was chasing that illusion of instant gratification even though I also wanted to learn these old techniques as a way to slow down the pathologies of our modern world’s obsession with instant gratification.

The Taller Pan ó ptico is also very special in that nothing is a secret. Anything you want to learn, whether it’s ambrotypes or albumen, Arturo will guide you through it. While alchemists are famous for working enigmatically, guarding their formulas with their lives, Arturo’s virtue is in his vision for sharing his knowledge so that artmaking and beauty can proliferate. In Spanish, the word for teacher is the same as master, maestro . For Arturo, being a teacher is as important as being a master artist.

Photographs by Arturo Talavera, courtesy of the author

Arturo believes that the more people are interested in reviving dying techniques, the more potential we have now and in the future for new types of interpretations and creativity. Working under this assumption, you are able to “understand that once you have what is left of the process in your hands, you have something absolutely unique,” Arturo explains. “To make it, you need a series of circumstances that allow you to achieve a good technical and visually aesthetic result.”

Art is a sum of its parts. By opening his repertoire to others and allowing them to make their marks in his notebooks, a true master can spin gold out of lead. Each time I watch Arturo do it and learn from him, my own notebook in turn is filled with my own interpretations and inspirations for making these processes my own.

“Teaching is a constant enrichment for me,” Arturo says. “What we try to do here is make the workshop as accessible as we can for everyone.” While he loves teaching now, he originally started offering his workshops as a way to pay for his personal pursuit of photographic knowledge and art making. These days, because of his openness with his caché of knowledge, Arturo is a fixture in the local visual arts community, both as artist and teacher. All of us, his students, joke, “If you’re doing art photography in Mexico, you’ve gone through Panóptico’s doors.”

It’s only a half-joke. When meeting a new artist, the first thing we usually find that we share in common is having worked with Arturo in some way, shape, or form. Many very special friendships and collaborations of my own have been born of the same stuff, like how I was able to start apprenticing at another studio by virtue of having worked at the Taller Panóptico first.

Arturo’s work and generosity with his craft have sparked a Latin American revival of analogue photographic processes in the digital age. Through both alternative printing processes and digital negatives, a photographer has an infinite array of techniques to manipulate and produce her photographs, but can still edit her images through her computer screen. For example, if she wants to explore themes of melancholy in her work using the color blue, she can use her digital negatives on sensitized paper in the cyanotype process, producing white and blue images in varying hues using natural UV light to delicately expose her images to her exact liking.

Photograph by Arturo Talavera, courtesy of the author

“There is no need to be a purist about it,” Arturo tells me, half chuckling. “Now with digital and antique hybrids, really interesting things are being done.” For example, in one recent project, Arturo scanned a daguerreotype, a type of image that only gives a positive image, in order to make a digital negative. From that digital intervention, he made a color carbon print of the image, layering about twelve different negatives in different colors to achieve the effect he was looking for.

I’m still wading through all the dizzying arrays of possibilities myself. There is always something new to learn, a process to recover from the oblivion of time, something to refine, or a new combination of techniques to try out. Every time I meet another student in the Taller or see what Arturo is working on, I realize the only limit to the possibilities in a hybrid digital-analog world is the imagination of the creator.

After twenty years of study, it seems Arturo has just about every process under the sun under his belt. I ask him if he could do it all over again, would he? What more could there be to learn or do if you already teach over twenty different workshops and produce your own work and take on printing and production for other artists? His answer is a contented grin that spreads over his face.

“Yes, I would absolutely do it again. I don’t think I would change anything,” he says, but then pauses. “I would have taken better advantage of my time, though, because I don’t think I did that so well in the past. I should have spent more time reading and researching and doing in the early days. But besides that, I would have done everything the same.”

Even though learning these analog processes is time consuming, expensive, and difficult, and I came to it later in life, the relationship and friendship I now have with my teacher has been built on the very things Arturo values most in making good art—patience and persistence. I learned things at the Taller Panóptico that I didn’t have the time to learn before, like patience, what the creative process looks like and how to work through it, and the value in sticking with something despite the challenges and setbacks. Every time Arturo told me not to worry about perfection and to focus more on learning the muscle memory needed to dip a metal plate into a silver bath when making my tintypes, his lessons sunk deeper into my head and lodged more firmly into my heart.

The purpose of art is not to create perfection. It is to bring something into the world that is a culmination of a very intimately personal creative process married with sound technique. True alchemy is teaching others how to transform their ideas into infinite forms of beauty. The magic ingredient seems to be time: time for forging relationships, time for learning, time for making mistakes, time for creativity, time for dry spells, and time for just enjoying the act of creating. When I work with Arturo and see him in his element, this is what I see in him, and what I am beginning to see in myself, too.

Photograph by Natalie Baur