On Writing Interviews

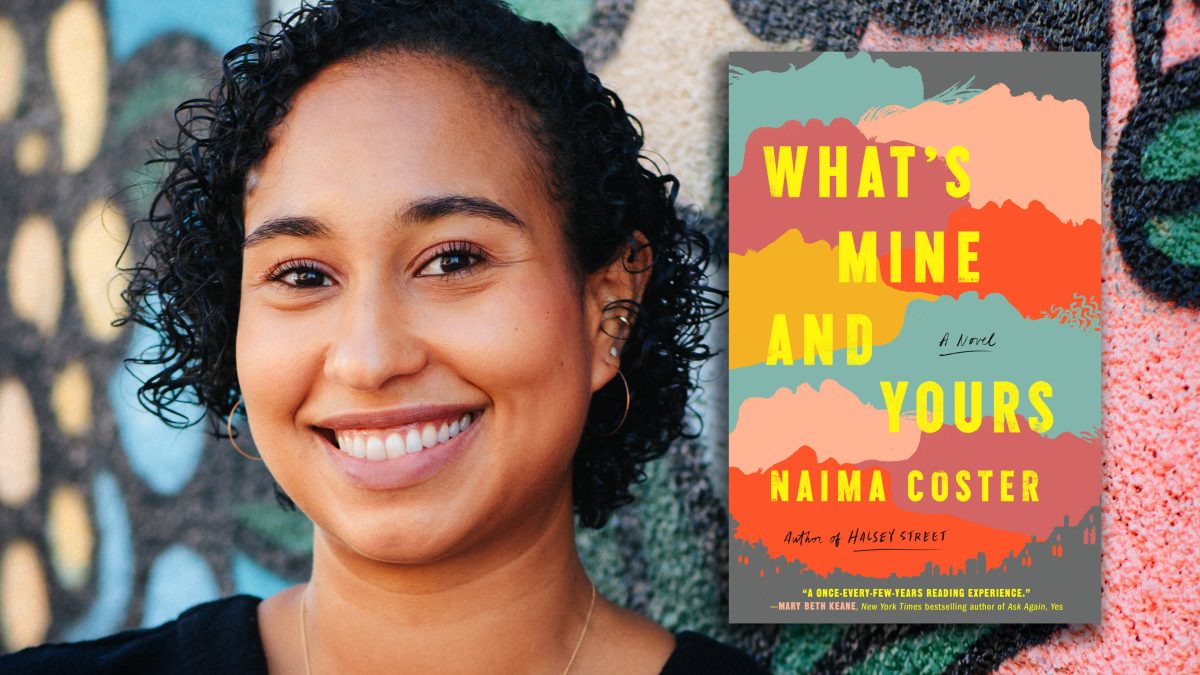

Let It Be Strange: A Conversation with Naima Coster, Author of ‘What’s Mine and Yours’

“The book is not straightforward, but it is expansive, and I don’t think the only way to make a story cohere is chronology.”

I met Naima a few years ago, when she came to Washington, DC, for an event to celebrate her wonderful debut novel, Halsey Street , at Duende District, a pop-up bookstore that highlights BIPOC writers. Over dinner with Duende founder Angela Maria Spring, we discovered that we were both part Dominican and had both attended Prep for Prep, a program that helps students of color earn scholarships to attend private high schools in New York City. Since then, it’s been a pleasure to watch Naima rise. Halsey Street was a finalist for the 2018 Kirkus Prize for Fiction, and Naima is a 2020 National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree .

Deftly weaving together multiple storylines and flitting effortlessly across time, Naima’s newest novel What’s Mine and Yours traces the ways in which the fates of two families come together and apart over two generations. Naima writes characters that bristle with a sort of electric irreverence, that seem to push at the margins of the page. Even after you’ve read the last page, you know that Jade and Lacey May and their children will keep on living, beyond the covers, and that their lives will intertwine again.

In late February, Naima and I texted about What’s Mine and Yours . As is the case with so many of our Covid days, we talked around internet outages and finding childcare during the pandemic. We talked about writer origin stories, legacies, and motherhood.

The conversation below has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Book cover by Grand Central Publishing

Yohanca Delgado: I know What’s Mine and Yours began with a short story that first appeared in Kweli Journal. What was the spark for that story for you? How did you know that the world of “Cold” could be expanded into a novel?

Naima Coster: When I moved to North Carolina, I spent three days snowed in and mostly alone in a little house at the bottom of a gravel road. We were broke and kept the gas on low to save money, and I was very cold and isolated. I wrote “Cold” over those three days because I was thinking about that feeling of loneliness, not having support, and trying to figure out your life. I made that character, Lacey May, a mother whose husband isn’t present and struggles with addiction. I considered the story a standalone piece.

When I started dreaming up my second novel, I knew I wanted it to be a kind of mosaic. I started wondering about bringing Lacey May and her family into that project. But I didn’t envision that they’d become such a focal point of the book. I thought the novel would be much more sprawling, and instead it really focuses on two families over the span of twenty-five years.

YD: Speaking of the span and structure of this piece, you describe it as a mosaic, which I love. As I read it, I thought, too, of a game of cat’s cradle, a very precise interweaving of timelines and character stories. I’m always interested in hearing how content shapes form for a writer. What inspired you to structure the novel in this way?

NC: That’s a terrific metaphor for what the book is—you pull a thread along, and the shape is, perhaps, unexpected but there’s still continuity, something to follow. I don’t think the book ultimately wound up being a mosaic exactly in the way I envisioned it.

When I imagined the book being centered around the integration initiative, I planned on including many more perspectives from numerous people in the city, so I could show the ripple effects of the change in the community. But as I became increasingly drawn to the figures of the two mothers I knew I wanted to write about—Jade and Lacey May—and started imagining their children, the book became a family saga about belonging and loss and legacy. And the integration became a smaller piece of the book, the incident that brings these two families and their stories together, and that raises some of the themes at the heart of the book.

YD: So much of the excitement of writing is the electric malleability of a work in progress! I can see how Lacey May and Jade became vortexes around which the rest of the story swirled too; they are such nuanced, compelling characters. In what other ways did the story shift and surprise as you wrote? And how did you negotiate between the desire to let the story go where it wanted to go and hewing closely to your vision?

NC: I had a fairly developed vision of the book at the beginning, mostly because I needed one to have the confidence to start! A book is full of so many unknowns, and it’s exciting, as you say, but I also find it daunting. But the book shifted radically from that vision, which is such a good thing.

Gee, in particular, is a character who I got closer and closer to in every iteration of the book. There are so many moments with him that I had to discover by going through the book again and again. A friend of mine told me he couldn’t imagine the book without the scenes with Gee that I added at the very end, and I said, “Well I could imagine the book without them, and I did.” The role of the unconscious in writing is so interesting—the things we dig into and the things we avoid. I found there were things with Gee I was avoiding in early drafts. Once I let myself go deeper with him, the book became much more than I had intended it to be.

The role of the unconscious in writing is so interesting—the things we dig into and the things we avoid. YD: Gee! One of my favorite moments in the book involved the staging of the Shakespeare play and the decision that Gee and Noelle make about their performance of Measure for Measure. They decide to “let it be strange.” And speaking of the unpredictability of the writing process, were there moments like that for you? Where you consciously opted for the strange over the legible?

NC: I think the structure of the book is perhaps strange, but it’s also fitting. In any given family, every person has an individual journey that shapes the collective life of the family, whether what they go through is known to their loved ones or not. The multiple points of view in the book, and the movement back and forth in time, creates a portrait of how so many singular choices and experiences intertwine to tell the story of a family. It is not straightforward, but it is expansive, and I don’t think the only way to make a story cohere is chronology.

YD: I’m also curious about your choice of Shakespeare play. Were there thematic echoes in Measure for Measure that you wanted to pull into the world of What’s Mine and Yours?

NC: Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare’s problem plays, which is interesting. And in the ending to my novel, I was certainly playing with the idea of great joy and devastation being present at the same time. Thematically, I was interested in the way the play investigates how people’s moral judgements and strongly held convictions lead them astray and create disaster.

That’s certainly what Lacey May is doing in her opposition to the integration and what both mothers are doing in the raising of their children. They’re headstrong women convinced that they’re right, but there’s plenty that they don’t know or understand about the consequences of their choices. It’s true of all the characters, really; what they can’t see or don’t know shapes their lives dramatically.

YD: I agree! I think your structure does justice to the myriad strange ways in which the world shapes us before we even know who we are. And there is also a sense of inevitability, a sense that the knot releases as the main characters claim ownership of their full lives.

But speaking of Gee and the high school threads of the novel, I’d love to hear about your process here, since you and I are both alumnae of Prep for Prep. Did you draw from those experiences to write about Gee’s experiences as one of the new Black students at the newly integrated Central High School? I recognized a bit of myself in those passages!

NC: I’m so glad to hear you recognized a bit of yourself in the passages—and yes, absolutely, I was drawing from my own experiences as one of few people of color in a largely white school. I wanted to show some of the pressure and scrutiny of that position. I felt very much that I had to prove I belonged there—to my teachers, my white peers, myself, and also my family.

There is some degree of guilt to be the person in your family who gets a shot to go further. Gee wonders whether he deserves what he’s been given—but it also doesn’t mean that what he’s been given is simply a gift. It’s problematic and lonely. He faces racism, and he also has to deal with all the instructions for life he’s being given by all the adults around him who want him, and the program, to thrive. It leaves him little space to just be.

YD: I remember that feeling too! And it was hard, in the moment, to see beyond the gift aspect of it, to see that the schools themselves benefited from the optics of increased diversity, even if it was a hard transition for us. In some ways, I think that those were the years that made me a writer, because so much about surviving had to do both with being an outsider and closely observing other people.

Courtesy of the author

NC: Yohanca! I think and have said the same about myself! That trying to decode the culture of my school and fit in made me develop the observation skills that have made me into a writer.

YD: I’m remembering, too, that the protagonist of Halsey Street, Penelope, struggles with these feelings when she attends art school. It’s stressful to arrive in a space that wasn’t built for you. You have to simultaneously learn that institutional language and new social dynamics. You’re tired when it comes time to actually learn what you came to learn. I love the precision and lucidity with which you capture that experience. Were there other major markers or life phases that crystallized your writing identity?

NC: I think you’re totally right that the story of Penelope holds so many of the questions and feelings from my private school and college experience: the alienation, the lack of a feeling of entitlement to being an artist, being routinely underestimated. And Gee has a different set of experiences: He’s an outsider not only because of his race but also because he’s got some trauma that he doesn’t talk about, that marks him as different from his peers.

That’s a deep part of my formation as a writer, too, I think: experiences of violence or hearing narratives of violence that were either big secrets or became myths, legends of family toughness. In this novel, I am writing about what happens, in part, when we never talk about our wounds or what we’ve lost. Both families are living with a lot of pain they don’t talk about or even admit to themselves fully.

For this novel in particular, I was also thinking through questions and aspects of motherhood that were interesting to me as someone who wanted to be a mother. I was pregnant in the drafting of the book and was a new mother in the rewriting of it, so I was endlessly interested in lots of desires and problems of early motherhood: the difficulty of holding onto oneself and one’s ambition, the presumed selfishness of choosing yourself over your child, the trouble of learning how to mother when you weren’t mothered lovingly or at all, mothering without support, struggling to conceive, losing a pregnancy, terminating a pregnancy.

YD: You’re tying together beautifully two ideas that I’d love to hear you say more about: the wounds and losses that we don’t talk about and the idea of new motherhood, which I think can be joyous but is also a wounding. I won’t say that it isn’t talked about, but I will say that the conversation about those traumas is kept to the margins because it is so individual, so feminized, so tied to the body. And I think that adds loneliness to the burden.

I’m wondering how your perspectives about motherhood changed between that first draft and the rewriting and how that shift in perspective helped you shape these characters.

NC: I agree that those conversations have been kept to the margins. It’s been powerful to see such public conversation about how the pandemic has disproportionately affected women, specifically women of color, and has pushed so many mothers out of the workforce.

I was pregnant in the drafting of the book and was a new mother in the rewriting of it, so I was endlessly interested in lots of desires and problems of early motherhood. One notable change between drafts was that I made the postpartum experiences in the book much harder. A breastfeeding mom became a mom who wasn’t able to breastfeed; this same character mentions that she still has pain, months after birth, and can’t ride her bicycle. And Jade, when recalling what life was like when Gee was a newborn, talks about being so unhappy and scared and working very hard to cover up those emotions so as not to traumatize her son. I had a much clearer sense of how difficult the postpartum time is: how physically hard it is, how plans don’t always pan out, what it’s like to live in the hormonal soup after birth. I made it all less dreamy, although I hadn’t realized I was idealizing.

YD: How has the experience of motherhood in the pandemic been for you personally?

NC: It’s been lots of things, and I’m not sure I have the words yet to do it justice and offer anything approaching a complete picture. What I will say is I was prepared for motherhood to be hard, but I wasn’t prepared for how full of joy and meaning it would be. I’ve always been suspicious of platitudes about motherhood, and I wrote them off because they didn’t ring true to me, so I wasn’t prepared for how in awe I’d be of my child, or how much fun and meaning there would be in sharing life with this little human.

YD: This makes me so happy! As we wrap up, I want to ask what feels like a stressful question to pose to a writer with a baby and a brand-new book to promote, as we enter year two of a pandemic, but: Are there new Naima Coster projects on the horizon? Are you finding time and space to write? (If yes, please share your secrets.)

NC: I am not finding time and space to write, certainly not fiction. I have written several essays since the pandemic started, but for me, novels take up so much more energy and mental space. I have a fairly detailed vision for a third novel that I hope to start writing soon. It’s about two longtime friends who move near each other while they’re both pregnant so that they can raise their kids together, but in doing so, they’re forced to confront the divergent paths their lives have taken: one toward wealth, a passionless marriage, and a pressing secret; the other toward financial instability, a creative dream, and harrowing isolation. It’s about new motherhood, female friendship, and class mobility. I can’t wait to make it real.

Photograph by Sylvie Rosokoff