Fiction Short Story

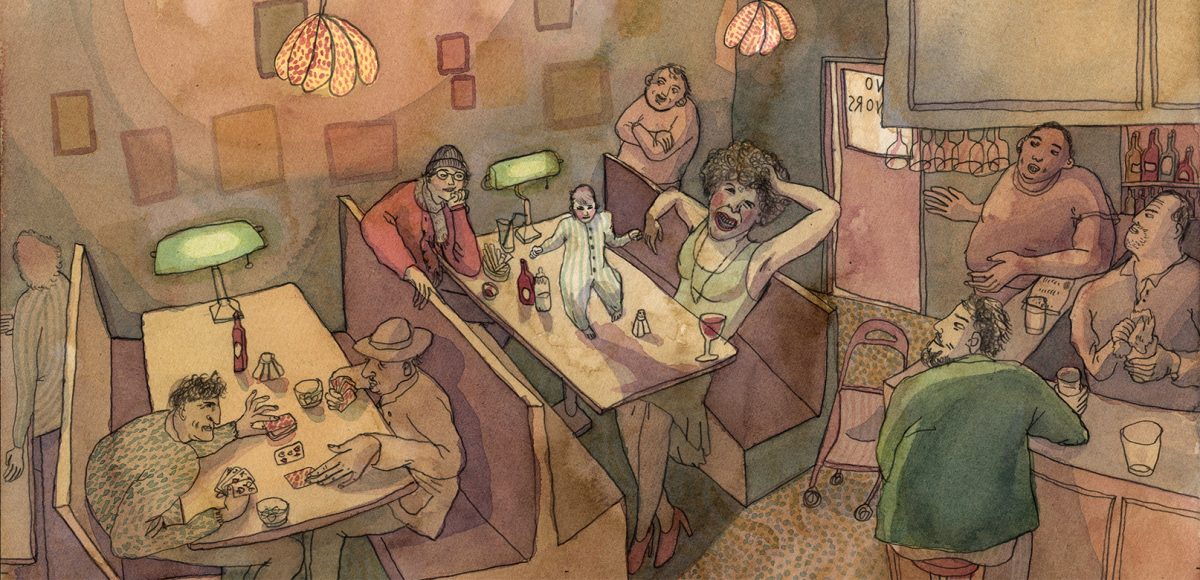

Baby in a Bar

“A sign in the window said No Minors after a certain hour.”

I brought my baby into a bar. It was the middle of the day. We’d been walking for hours as if pursued, and it had started to feel as if we wouldn’t stop until we slammed into something.

The bartender registered no interest or alarm at the sight of me pushing my behemoth of a baby stroller up and over the lip of the threshold. A sign in the window said No Minors after a certain hour, but it was too early in the day for it to be after anything. I was rain-damp and heated by a vague sense of panic. Had we been being followed, we had just entered a blind alley. The lone other customer sat at the end of the bar with a pint and a newspaper. I asked the bartender for a soda water with a lime. I tilted my eyes at a food menu and added French fries to the order to pay more rent, so to speak, on our presence there.

Who was after my baby and me? When we’d begun our walk hours earlier we’d been fueled by our own internal motors—my need to get out of the house, my baby’s need to get sleepy, then nap, then my and my baby’s need for him to stay asleep for as long as was necessary to not destroy the day. We’d walked and he’d slept, longer than I’d have thought he would have, and he woke up and still we kept walking, didn’t turn around, didn’t look for a park. We ranged into micro-neighborhoods I hadn’t known existed—quiet pockets of loud neighborhoods, raucous strips of quiet ones. In some crowds we were invisible.

The bartender shot my soda water into a glass. My baby made one of his speech sounds. I was trying to not attribute meaning or signification to them. To do this seemed cloying, and manipulative of whoever else was around, bending their ears to my interpretation. A friend of ours had recently stopped by when my baby was in the bath and overheard his habitual buh buh buh . “Boat!” our friend said. She pointed to the measuring cup he was floating around. “Is that your boat?”

If the bartender cared about babies, in his bar or in general, he didn’t show it. Not to say that a woman bartender would have necessarily cared any more about babies, but I would have cared more about what she thought. I took my drink and pushed the stroller to a back corner booth. This was just the kind of bar we’d needed: clean wide booths of waxed wood and green-shaded barrister lamps, a Cheers-y drop-in vibe that wouldn’t get going until we were long gone. If circumstance forced us to still be there when the place filled up, I would use the opportunity to explain to my baby that one might find family anywhere. Later, when his neurons had spun their fatty coats more thickly, it would be fine with me if he found some of his family on TV.

I got my baby unbuckled and stood him up on the booth cushion where he could hold himself up with the table’s edge. The surface looked clean, it was early in the day and it was a clean sort of bar, but I knew that clean surfaces should also be cleaned of their cleaning products before my baby touched them. I could picture the packet of antiseptic wipes in the bottom of the diaper bag. My baby grabbed the salt shaker. I moved to take it from him, but I could tell from the way he banged it against the table that it made him so happy. The germs of the city had already accrued to us. I didn’t want an antiseptic baby. I left the wipes nestled and unzipped my baby’s jacket, which my baby’s other mother called a sweatshirt. The material was cotton and quilted, but I was certain the extra-long hood marked it as an outdoors garment. I unzipped it halfway and thought that that might feel strange or uncomfortable for my baby, so I unzipped it all the way, more flapping and inconvenient, so I took it off him entirely, though I was still wearing my jacket and a woolen watch cap. “Are you cold?” I asked my baby. I touched the tip of his nose and he giggled.

I knew it was important to talk to my baby before he registered understanding. On our walks, I narrated our surroundings to him. Earlier that day we had walked past a bakery and I had described to him the display of old-looking but dust-free models of birthday cakes, I’d noted the two outlets we passed of a marginal coffee chain trying to reinvent itself as the antidote to Starbucks. I spoke quietly and tried to move my lips as little as possible, so as not to appear as if I were talking to myself, though I raised my voice when we passed other babies and parents so that I could showcase my investment in communicating with my baby.

When I was out in the world with my baby and I saw other adults, presumed parents, with their babies, what I felt wasn’t exactly something I’d call kinship. I didn’t know anything about them but I knew about what they did. I knew their routines and materials. This didn’t make me feel closer to them; what we had in common was too obvious. That morning, we’d approached what I assumed to be a mother and her baby just as my baby had fallen asleep, but I had no choice. I said to my baby, “Some people say Starbucks ruined the independent coffee shop, but others say the increased competition benefitted smaller businesses. When you get old enough to drink coffee, there may be only Starbucks, or no Starbucks.” My baby cried at me for waking him up, then fell back asleep. A few blocks later, we walked past a payphone. Within another block, we passed a phone again, as if we’d gone back in time. I was reminded of a short story I liked where the narrator keeps calling her boyfriend from a payphone and he keeps hanging up on her. Actually, she never uses the word “boyfriend.” Eventually she calls from a different phone and he answers and they make a date to meet for lunch. She is convinced that he has decided that he doesn’t want to live with her, and it’s not until he mentions the “crazy person” that kept calling and hanging up that she realizes the phone she’d been using was broken. We passed a parent and baby and I whispered to my baby, “You will probably never use a payphone.”

The bartender brought over our French fries. I pushed them across the table from us, though my baby didn’t like potatoes. He liked pickles, and zucchini, and bananas, and Cheerios, a small container of which I pulled out of the diaper bag, unlidded, and placed on the table in front of him. Counting the hours backwards, I realized it was time for a bottle and I got one out of the cold pack. Where we were felt hidden from the bartender’s station, but he could emerge at any time and ask us how we liked our fries, or if I wanted another seltzer, though I sensed he planned to ignore us. If I needed to, I would explain that my baby was drinking breast milk that had been expressed by his other mother, not cow milk, which I surely would have bought off the menu if they had it and he drank it. I laughed out loud.

While my baby was distracted with his bottle and cereal, I felt for my cell phone and looked at the screen. How is it going? my baby’s other mother, the woman I’m married to, had written. I reserve the word “wife” for extreme cases. Good! I wrote. The baby had a nice long nap . I would explain about the bar later. I might say that I was hungry and we’d stopped for lunch, that it was the only open place around.

I ate a French fry. This wasn’t the kind of bar I’d ordinarily go into. The people who worked and drank at the bars I ordinarily went to wouldn’t have expected to see me with a baby. Those were bars people went to to forget they had parents. In those scrappy, star-tarped worlds, babies didn’t exist. I said to my baby, “I was never exactly a regular.” I was regular enough to be recognized, but not enough to be known by name. “Do you know my name?” I asked my baby.

When I was out walking with my baby and we passed other presumed parents with their babies, as I spoke audibly to my baby about the world, I didn’t know how the other parents saw me, or who they saw me as. Was I mother, father, “aunt,” nanny? Did I look the appropriate age to be a parent of this baby? Did the casualness of my clothing not match the pedigree of my stroller? Why was everybody so touched to see dads in the park with their babies on a Saturday morning, letting the moms sleep in?

“Should I get a beer?” I asked my baby. “No, no,” I said. “Forget I said that.” He shouldn’t have the pressure of making that call. I got my baby’s favorite book, Baby Animals , out of the diaper bag. Baby Animals begins with photos of kittens and moves on to puppies, then a sharp turn toward the esoteric with a two-page spread of baby guinea pigs. In the spread on Australian Babies, every baby is called a “joey.” The final section is Animal Families. Cuddling pandas, intimate-yet-wary llamas. A photo of a caterpillar and a butterfly. “Chosen family,” I said to my baby.

My baby handed me his bottle and said “More?”, his one recognizable word. “We don’t have any more right now,” I said. My anxiety hitched up a notch. I had never wished that I had been the one to breastfeed my baby, just as I had never had the desire to be pregnant, though giving birth, even after what had happened with our baby, seemed interesting. Giving birth happened in relative private, whereas pregnancy and breastfeeding drew public attention to one’s body, in this case, one’s female body, an attention I typically chose to deflect or deny. My baby needed a diaper change, an inevitability I’d been suppressing since we’d arrived at the bar, and he would have handled the experience more calmly with a bottle in hand. I found his bottle from earlier in the day, unscrewed both lids, and poured the few remaining drops from the old bottle into the newer one, saying, in what I hoped was a tone of abundance, “Oh look at that! We found more milk!” Not allowing myself to notice where the bartender was and whether he was watching us, I put out the changing pad on the booth, got a clean diaper and packet of wipes, lay my baby down with his bottle—“All that yummy milk!”—got his pants down and onesie unsnapped and his diaper undone, and I cleaned up his poop, which had been relatively undramatic to deal with since he’d started eating solids. The dirty diaper went in a gallon Ziploc baggie, kept for these purposes.

I scooped up my baby and nuzzled my nose into his neck until he giggled. The bar, I realized, was silent. No music—had there ever been?—and the bartender and the lone patron were gone. I intuited the smell of marijuana from the cracked back door. “Where do you think we are?” I said to my baby. “This is a bar, where some grownups get drinks that help them relax, and some of them get food or water. Your mom used to go to bars a lot, before she met you and even more before she met your mama, and she doesn’t exactly miss it but she does miss—the sense of timelessness?” If I had gone into one of my old bars, even without my baby, there might have been a whiff on me. I sat my baby on my lap, facing me. “It’s hard not to feel like a cliché,” I said. It seemed as if I should have spent more time staring at my baby and wondering what was going on in his mind. Constant small sparks, amounting to nothing I’d recognize as thought.

This was the point at which I should have packed up my baby and taken off, but we were immobilized by comfort. We had so many French fries left. The front door pushed open, letting in the unthinkable daylight, and a man came in. Without stopping at the bar, he walked over and sat at the booth across the aisle from us. It was as if we’d been waiting for him. “Is that your baby?” he asked. He looked like a deflated Donald Trump. He was wearing a suit that looked too small and too big for him.

“I have a copy of his birth certificate,” I said, holding my baby tighter. Already I was in trouble. It wasn’t a copy. I had a copy but I’d lost it, so I carried around the original in a gallon Ziploc baggie in the side compartment of the diaper bag. I kept meaning to put it between cardboard so it wouldn’t get bent.

“He doesn’t look much like you, does he?” the deflated man said.

If we had been on a bus or in a crowded room I would have shrugged and turned to pretend to let something else distract me, but the bar was empty. “Were you following us?” I asked. The man stood up. “He’s my baby,” I said.

“What’s his name?” the man asked. We so rarely used our baby’s real name, choosing instead from our endless list of cutely non-sequitured diminutives, names we used to call the cats. Still, I was as scared to lie as I was to tell the truth. I said my baby’s name. The man sat back down but kept his body angled toward us, as if he might stand again. “Call him,” he said.

“Call him?” I said.

“Go over there and call him.” He took a sip from a glass I hadn’t seen before.

“You mean, by his name?”

“By. His. Name.”

I’d been the first person in my family to see my baby. My wife and I were supposed to see him at the same time but she couldn’t get numb for the emergency c-section. They kept flicking her and saying “Can you feel this?” They could tell when she was lying. They said, “If you can feel this, you’ll want to let us know.” My beautiful baby, whose skin I had held against my skin while my wife dazed out of the anesthesia, could sit up but not stand up by himself. I set him up in the booth. I handed him a French fry. I slowly backed up into the middle of the room, until I was about ten feet away from him.

I said his name. He chewed the French fry.

I said his name again.

My baby made one of his speech sounds.

I heard clapping from behind me—the bartender, and a white-coated cook from the kitchen. “Lucky,” deflated Donald Trump said, and he walked past us and out of the bar. My baby was a fucking angel. I ran back to my baby and kissed him, squeezed him, smelled him, got his hair in my mouth, touched his four tiny teeth.

I love my baby’s teeth. I hope he never gets braces. I hope he gets glasses. We can share the feeling of living the first few seconds of every day in a blurred, unfixable world.

The bartender brought over a round of whiskey shots and I had to say yes. We would get a cab home. As the bar filled up, everyone came over and said how cute my baby was, and, respectfully, nobody asked to hold him or said that the hours for minors were over. I let him eat two more French fries. I let him play with the Rhea Pearlman archetype’s keys. I told Rhea Pearlman the payphone story and before I was halfway done she said, “The phone was broken, right?” Music came on, the Kinks, my baby’s favorite, and I let him stand on the booth cushion holding on to the table and do his best baby dance, the one where it’s like rhythm is falling on him in fat, sloppy drops.

My baby’s other mother would be getting home from work soon and wondering where we were. “My joey is getting tired,” I said. “My wife is expecting me.” I didn’t ask the newcomers if the deflated man was hanging around outside. I knew he was.

“Stay!” everyone said. “He can sleep in his carrier, don’t you have one with you?” Of course I did. I had two. I got him fixed up in the Ergo so he curled against me like an animal and then I got out my phone and texted my wife. I told her where I was and said she should come down and join us. Take a cab , I wrote. It’s great here , I wrote. Everybody knows my name .