Family Grief

My Mother Has Terminal Cancer, and I Can’t Seem to Stop Buying Sweaters

I’m stockpiling sweaters because they signify refuge, collecting them like talismans though grief cannot be avoided.

My mother is always cold. Growing up, we would tease her about this, my father, sisters, and me. We lived in Virginia Beach, where the air slumps, moist and warm, and where the mere sight of a snowflake triggers citywide dread. What’s more, Mom spent the first two decades of her life in Connecticut and Pennsylvania—surely the tepid winters of coastal Virginia could not perturb her.

And yet, if the temperature slipped below 55 degrees, she would prepare to take the dogs for their nightly constitutional by swaddling herself in a hooded, ankle-length parka. Its color—a flesh-adjacent taupe—and its bulk have the effect of transforming its wearer into an upright, roly-poly caterpillar. Laugh all you want, Mom would declare, as we giggled from the kitchen table, but I’m warm. And so she’d set off with our father—he sporting an unzipped suede jacket, or perhaps a sweatshirt, if anything at all—and they would make their way around the block, two meandering figures tangled up in leashes and three love-flushed decades of marriage.

My mother is now too sick to walk dogs. She’s too sick for everything that previously shaped her life due to the paramount and unremittingly vicious effects of ovarian cancer, diagnosed three and a half years ago. Since then, my family has measured time according to her chemotherapy schedules, recalibrating according to treatment results: “the new normal,” we’ve designated it.

For my part, this grotesque approximation of normalcy has spawned several unremarkable byproducts: surges of impotent fury, tears—a greater quantity than usual, for a stoic I am not—and a neurotic reluctance to settle future plans. The one question that previously reared its malignant head every several months now grips my brain like a vise: “How long will my mother live?”

A more trivial effect of her cancer: Most of my shopping budget has now been allocated to sweaters. I’ve entertained brief flirtations with flannel button-downs and the rare cropped sweatshirt, but ultimately determined that they supply only pale imitations of a sweater’s particularly intimate snug. By the end of last summer, as CT scans and blood tests yielded increasingly dismal tidings, my partiality to knitwear intensified to a mania. Washington, DC heaved with stubborn, swampy humidity; I—with similar persistence—rummaged for merino wool and thermal cotton in the sale racks.

If you’re in the market for mourning attire, sweaters are an obvious choice. Their heft and design generally anticipate emotional vulnerability and the yearning for tactile sympathy. A sweater doesn’t extend sterile pity; on the contrary, it supplies comfort through dependable functionality. With climate as the only major caveat, we can rest assured that the experience of wearing a sweater will remain consistent: It felt good yesterday, and so it will today, too. The thick, wooly yarn; the cable knitting—their sensations are durable, as are their fibers. It’s common for a person’s wardrobe to outlive them; if we care for our sweaters, they are certain to do so.

My mother was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and she grew up nearby, in Milford. Her cheeks are softly dimpled. She was a nurse before she committed herself to raising three daughters, of which I am the eldest. She knows the precise way to split an English muffin so that the halves are approximately equal in circumference (you poke it around the middle with a fork). I inherited from her an emotional porousness; she is the most empathic and openhearted person I know. I aspire to emulate her and fail all the time—but I do know that because of her, because she made me, I feel the world in my bones, and that is why I write.

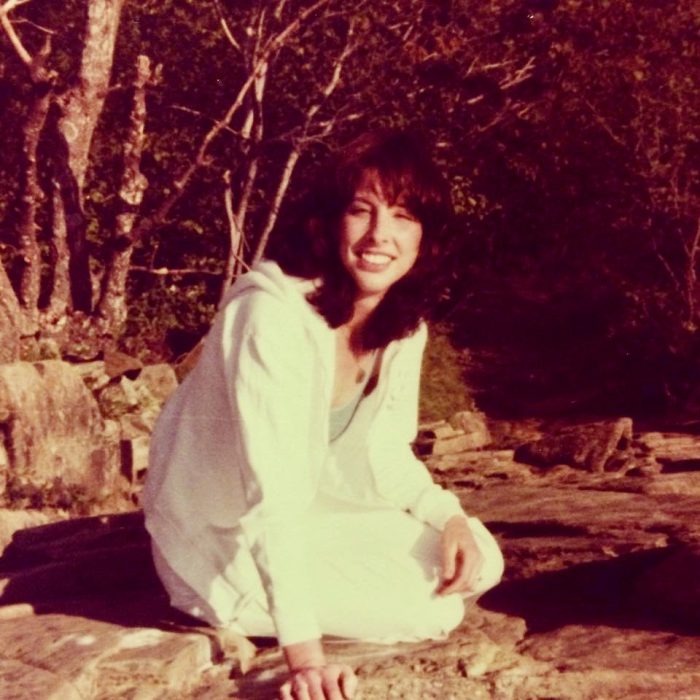

photo of the author and her mother

You might suppose, rightly, that because my mother is always cold, she is diligent about packing sweaters for nearly every occasion. She opts for earth-toned cardigans—tans and greens, mostly—with loose, draping cuts. Her standby sweater is a heather gray button-down of thick jersey material, worn at home and during brief, informal errands. I don’t remember a time before this cardigan, and I saw it as recently as two months ago, when I was home for a visit. It was laid out neatly in her bedroom, awaiting use. I picked it up gently—I cannot replicate Mom’s impeccable folding—and pressed it to my nose. Perhaps this sounds theatrical, or even kind of weird. But it smells like my mother, like the memory of white flowers, and my mother smells like home.

Lately I’m disturbed by scent’s ephemerality, because I know there will come a time—it’s a matter of science—when my mother fades from the stitching of this cotton cardigan. She’ll fade from the rest of her clothes, too, or my sisters and I will imbue them with our own blends of perfume, soap, and skin. There’s some comfort in the latter, because it supposes an entangling; an embrace made possible through scent after there’s no longer a body to hold. What are people, after all, but clumps upon clumps of atoms, permeable and unfinished? We’re always mixed up with each other, blending at the labile borders of “me” and “you.” We carry away traces of one another—incorporate them into ourselves. It’s not so far-fetched to believe that we could hold onto someone after they’re dead.

And yet I’m stockpiling sweaters in a pursuit of immunity—because, collectively, they signify refuge. I can swathe myself in chenille or wool or—if I’m feeling luxurious—cashmere, and pretend the deep hollow spooned out by loss has been stuffed brimful with fabric. I can fantasize about warmth so infinite that even the most strident heartache is muffled and, at last, smothered. A sweater, a sweater! My kingdom for a sweater.

But what about my mother? What could I give in exchange for her?

I know that I’m operating on the level of superstition, collecting sweaters like talismans in order to stave off what I already understand: Mourning cannot be circumvented, and some holes cannot be plugged. These are inconvenient, frightening facts. Beneath my sweaters I’m flimsy and shaking, and though I button my cardigans to the neck, grief will find me like a dart to a bull’s-eye. I’m obliged to accept it as the unwieldy thing it is—to hand myself over to time and the balm its passage brings. One day, perhaps, my grief will become something more accommodating and portable, with decipherable edges, and I’ll fold it up like a sweater and tuck it into one of my heart’s crevices, to keep company with love and memory.