Columns dis/fluent

How Vlogging Is Empowering a New Generation of Stutterers

They ground me, authorizing me to keep talking like I do.

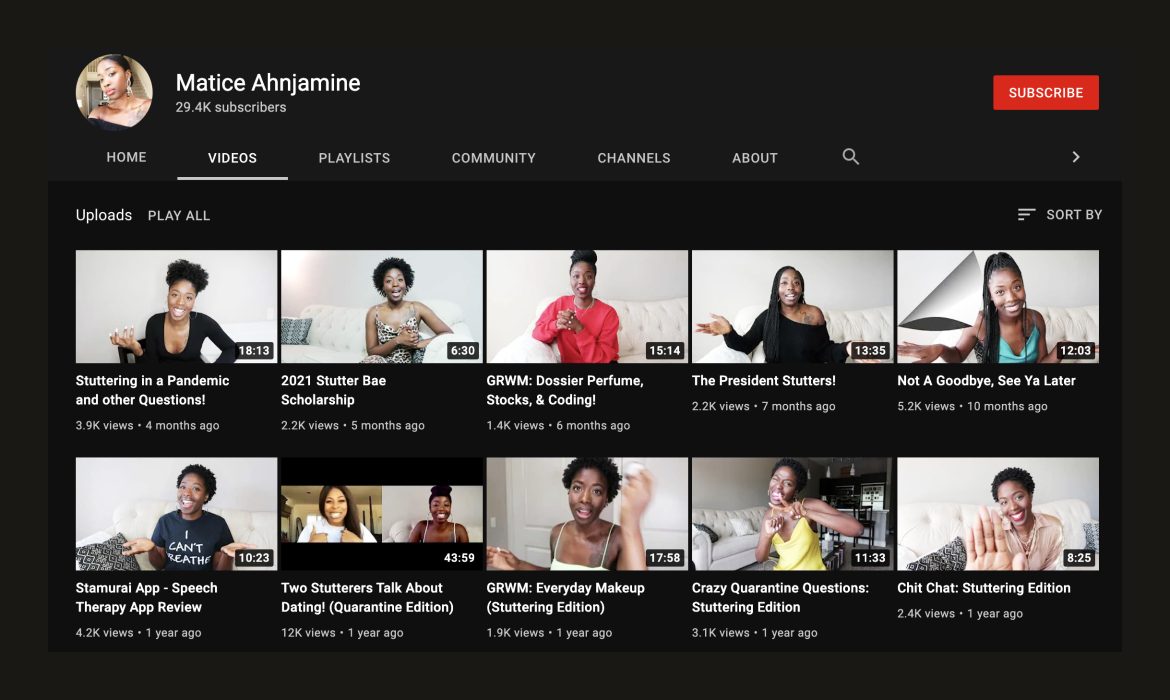

This is dis/fluent Four years ago, Matice Ahnjamine filmed her first vlog. Ahnjamine, gorgeous in red lipstick and box braids, stands against a monochrome background and introduces herself to new viewers. “Welcome t-t-t-t-to my YouTube channel,” she says. “As you can ssssee I stutter, and that is why I wanted to start this YouTube channel.” Over the next five minutes, she describes how most of her life she felt alone until, at twenty-eight, she met another person who stuttered. It was exhilarating to encounter someone who spoke with “long pauses” and “made these crazy faces like me,” and now she wants to offer that same sense of connection to other people through her videos—to let us know we’re not alone.

I can imagine what Ahnjamine’s channel might have meant to me had it existed in those early, uncomfortable years of accepting and defining myself as a person who stutters. I had no role models to look to, and all the depictions of disfluency I saw came refracted through able-bodied performers in movies and on television—actors who wore disfluency as a costume. I only heard impressions of stutters, never real ones; I knew only characters who stuttered, not people.

This is still the case for most nonstutterers, whose points of reference for disfluency are usually either works of caricature or inspiration porn. The disclosure of my disfluency is sometimes met with invocations of scripted films: Oh, like The King’s Speech ? like The Waterboy ? like A Fish Called Wanda ? But these are scripted stories, anchored by people pretending to talk like me. In these films stuttering is a dramatic obstacle, a tragic flaw, a character-defining challenge. Ahnjamine’s videos, on the other hand, give first-person insights into the experience of disfluency and impart that stuttering is what we do, not who we are.

Since her first video, Ahnjamine has uploaded nearly seventy more. In most of them, she answers stuttering-related questions: “How Do I Work With My Stutter?” ; “Why Do I Tap When I Stutter?” ; “Do I Stutter When I Sing?” She discusses the Stutter Bae scholarship fund she’s started. She interviews other people who stutter. But in many videos, she simply films her everyday life: There’s a closet-cleaning vlog, a birthday-dinner vlog, a makeup-routine vlog. She hits the mall, gives viewers a tour of her new Tesla, goes skydiving, attends a bachelorette party, gets her first sew-in. And in all of her videos, she stutters—casually, comfortably, and confidently.

I didn’t find Ahnjamine’s videos until I was well into college, already immersed in the stuttering community by way of the National Stuttering Association. At chapter meetings, I regularly communed with a dozen other people who stuttered and discussed disfluency. But her videos gave me something I couldn’t always get from meetings, which are supportive spaces to unload shared frustrations and traumas. Some of Ahnjamine’s videos deal with stuttering-specific frustrations and traumas, but many of them don’t. My favorite vlogs of hers provide a peek into the fairly normal existence of a fairly normal person. It feels extraordinary to hear a stuttering voice talk about something besides stuttering. To witness a stuttering life that isn’t all heaviness and suffering, that is perfectly ordinary, even joyful.

As a much younger stutterer, I often typed the word stutter into Google and social media search bars clandestinely, with a hot face and racing heart. I was looking for proof of my life. I was desperate for evidence of reproducibility—the results of a scientific experiment are legitimate only if they can be reproduced over and over again, and I needed to see myself over and over again to know that I was real. But my searches came up short.

I found that entering the term stutter on YouTube yields particularly dispiriting returns—lots of videos about stutterers but hardly any by them. You’ll find instructional videos that tout cures for stuttering, inspirational interviews with people who overcame their stutters, clips of Steve Harvey and Tony Robinson berating stutterers for their lack of gumption. But add a single word to your search— stutter vlog —and you enter a different realm. On the “stutter vlog” results page, you’ll find Ahnjamine, as well as vloggers like Paige White and Téa Paige , who have shared their lives and their stutters with strangers on the internet for the last few years.

Last summer, I downloaded TikTok, and, as if I were a teenager again, I searched stutter in the app. I found the sorts of videos I expected—clips of nonstutterers stumbling over their words, jokes that ended with the punchline “Did I stutter?” But I was shocked to find a subculture of stutterers on the app who were using micro-vlogging with incredible deftness. TikTokers like Caitlyn Cohen , Jane Burdett , and Ryleigh Spetoskey have each created hundreds of videos that capture not just their disfluency but their personalities.

Like Ahnjamine, Cohen and Burdett and Spetoskey are sprightly, pretty, and naturals in front of the camera. The personas they’ve crafted don’t begin and end with their stutters. They post often about stuttering—dispelling myths, responding to comments, sharing anecdotes—but they also post about other things that matter to them: horoscopes, Harry Styles, eyebrow brushes, Twilight , soccer, Hamilton . I watch them and they seem so young, all still in college. I think of myself, at seventeen, seeking out the National Stuttering Association, desperate for support and validation. Meanwhile, these young women are broadcasting their speech for the internet’s consumption; they’re growing with and into their stutters on camera. I could never have done that at their age—I still can’t.

I think of myself, at seventeen, seeking out the National Stuttering Association, desperate for support and validation. I’m especially fascinated by the hybrid role Cohen has fashioned for herself as both an activist and an influencer. She boasts over 1.1 million TikTok followers, and her popularity feels significant: She possesses no extraordinary talent that would put her in the category of “ supercrip ,” and her disfluency has maintained its severity over time. She’s celebrated not for overcoming her disability, but for embracing it proudly and publicly. This is the message she promotes through stints on Disney Channel, spots on morning shows, and a partnership with Victoria’s Secret. But disabled people are under no obligation to be full-time role models. I revel most in watching her behave like the vibrant young woman she is—posting bikini-clad thirst traps, gushing over her boyfriend, posing cheekily in a T-shirt that reads “Hydrate, Meditate, Masturbate.” These sorts of posts would feel off-brand and out of place for peers like Burdett or Spetoskey, and I relish the sheer breadth of stuttering vloggers. They show that we’re not a monolith, that we share a trait and possibly nothing else.

That YouTube and TikTok are audiovisual platforms is vital to normalizing and demystifying disfluency. I’ve inferred, after many years of uneasy reactions, that the sight and sound of my stutter are distressing to the average person. Are you okay? they ask. Do you need water? Is this, like, a stroke? And my favorite, the ever-direct What is happening? I get it. Folks are, understandably, trying to make sense of the aberration before them. I’ll be the first to admit that stuttering looks and sounds very weird: The face contorts, the voice lurches; sometimes the eyes shut or the mouth grimaces. In many cases, this weirdness is cause for genuine, well-intentioned concern.

Roland Barthes gets to the root of this concern, writing in The Rustle of Language that stuttering is like “the knocks by which a motor lets it be known that it is not working properly . . . the auditory sign of failure which appears in the functioning of the object. Stammering (of the motor or of the subject) is, in short, a fear: I am afraid the motor is going to stop.” Many of my listeners are simply afraid for me, which I appreciate. At the core of disfluency is something extremely difficult for many people to grasp. Most able-bodied people can’t imagine knowing what you want to say yet being physically unable to say it. But disfluent vloggers are introducing new possibilities to the able-bodied imagination: that stuttering is not a defect or a failure. It’s just a way that some people—otherwise “normal” people—talk.

Ahnjamine and Cohen’s faces contort, voices lurch, eyes shut, mouths grimace, but their buoyant attitudes assure us that the object—the body—is functioning just fine. Their apparent comfort osmoses through their videos. This is, in part, a survival tactic: Making listeners comfortable is the central obligation of people who stutter. As a result, I spend considerable time thinking about how nonstutterers must watch these videos. What must they think? Feel? Why are they tuning in in the first place? I worry that they’re more spectators at a freak show than active listeners in a conversation. I’m so occupied by their impressions that I don’t consider my own.

I don’t watch these vlogs for fun. They’re more nourishment than diversion. More vegetables than ice cream. I love hearing people stutter during chapter meetings, exchanging ideas and sparking off each other. But seeing people stutter on camera can be tough—I still can’t watch or listen to recordings of myself stuttering. So I cue up stuttering vlogs when I need perspective. They ground me, authorizing me to keep talking like I do. Look at these young women who feel entitled to take up space, who have decided their speech is worthy of documentation and propagation. Look—your pain isn’t special, they’re going through exactly what you are, and they’re just fine. Look! Just talk like you talk! That’s what they’re doing, and if they can, then you can too!

I don’t like Ahnjamine and Cohen and their vlogging peers because I think they prove our humanity or show we’re worthy of patience and respect. Trying to court able-bodied empathy is as futile as it is demeaning. Rather, I like that they confirm that I do, in fact, exist. That I’m not an aberration or a glitch in the matrix. That there are other young women (and it is notable that these hypervisible stutterers are all women since we make up the vast minority of people who stutter) who live and feel and talk like me.

This is what happens when people who stutter graduate from objects of the able-bodied gaze to the subjects of our own experience. When we turn the camera around and capture ourselves in our entirety. When we stop being characters and declare ourselves people.