Columns Daughters of Eve

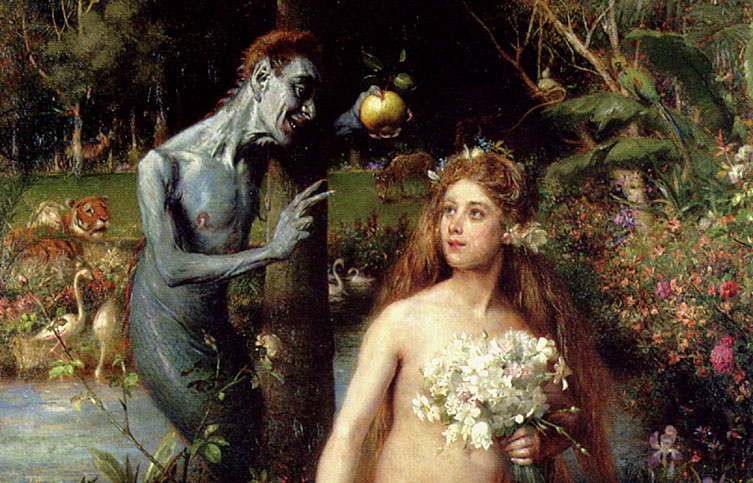

On Eve’s Temptation and the Monsters We Make of Hungry Women

There is a part of me, even after so many iterations of faith and years of living in an adult body, that is waiting for punishment, waiting to be banished from the Garden.

This is Daughters of Eve, a monthly column by Nina Li Coomes which uses women of the Bible to dissect ideas about womanhood, power and what it means to be “worthy.”

For me, everything starts with the body.

As a child, my mother often stopped to ask me where a feeling lived inside of myself. What color was it? What shape, texture, temperature? As a result, I’ve grown into an adult that roots everything in her physical self. Pleasure, pain, joy, sadness—all of it lives tangibly in me. Pleasure is a shroud of blue ribboning my waist. Pain is a throbbing rust lodged above my tailbone. Sadness hangs over my ribs in a yellow-gray film. Even faith is a slashed diagonal of gold heat in the dark corridors of my throat. I feel it flickering, glowing, inexplicable and alive. Each part of my self, anchored and physically real.

Hunger, though. Desire. These, I tell myself I have no place for. These, I have always tried to banish.

*

In the Christian faith, Eve is the first woman, the mother of humanity, and the catalyst of sin. We meet her first in Genesis, where she is the unnamed, naked product of Adam’s rib. She is born because God deems that Adam should not be alone. Essentially, she is created chiefly to fulfill the human desire for companionship, that ungainly grappling for another person sharing air next to you. In a way, she is the beginning and end of desire, both the answer and question of loneliness.

Many of us know the story. While living in the Garden of Eden, Eve is approached by a serpent who asks her about a fruit-bearing tree. She parrots what she has been told, that God has forbidden Adam and woman to eat from the tree in the middle of the garden, lest they touch it and die. The serpent tells her that this is untrue; that instead of death, “her eyes will be open.” Eve sees that the fruit of the central tree is “good for food and pleasing to the eye” and so she eats it. She takes some home to Adam, who also partakes. They discover they are naked, God discovers their sin, and so they are banished from the Garden of Eden. Before they leave, God curses the serpent to crawl in the dust, curses Adam to toil and sweat, and curses Eve with pain and longing, saying:

“I will make your pains in childbearing very severe;

with painful labor you will give birth to children.

Your desire will be for your husband,

and he will rule over you.”

Then, only as they leave, does Adam give Eve her name.

*

What does it mean to be a woman of faith who is hungry?

I first began to think of Eve as a woman punished for hunger in college. At the time, I was a recovering Atheist relapsing into her own disordered eating patterns. One evening, I struck upon this epiphany while staring intensely through the crosshatch glass of my apartment’s oven, willing the verdant kabocha squash (lower calorie count than sweet potatoes) I’d placed there to roast faster.

I was starving then, each obsessively planned meal barely enough to get to the next one. Every morning, I woke up and ate a banana on the way to the pool where I would swim laps for a neat forty-five minutes, bookended by a visit to the scale. At lunch, I sat cross-legged in front of my laptop eating from a never-ending tub of shredded cabbage, lightly dressed. For dinner, I ate carefully portioned roasted squash, sauteed kale, and a block of plain tofu. (It is shameful to me that I remember the details of each preparation, even now as I write this seven years later.) Each meal was designed to feed at the bare minimum, to tame and control a hunger I thought of as an unruly beast, each day, each meal, an attempt to divorce it from myself.

That day, staring at my squash, shifting my weight so that I couldn’t hear my stomach growling, I began to think of the obsessive quality of hunger. How it changed my personality, making me sharp and snappish, and how eating anything made me feel not satisfaction but a hushed relief. Sitting on the floor, my knees pressed into my chest, my arms clutched together, I felt that hunger made me primordial somehow, more animal, closer to my origins. This mingled with years of Protestant Sunday School teachings, and so I found myself wondering if Eve, the ‘original’ woman, had simply said yes to the serpent because she’d been hungry. Had Adam known to feed her? Had she been able to feed herself, nameless as she was? If you were starving, had been starving for days, wouldn’t you have taken the fruit too? Could the entire fall of mankind from God’s grace be pinned on a woman who simply had the misfortune of being hungry?

Conversely, a woman sickened with sin is one who is riddled with said hungers, reduced to a gaping mouth never satisfied. The oven dinged. I ladled kabocha onto my plate. I lifted a forkful to my lips. The irritable, discordant clanging of my thoughts shushed. A blanketing solace buzzed over the harsh edges of my appetite, becoming silent and orderly.

*

I was not born into a faith tradition. In Japan, I attended a Lutheran kindergarten and, as a result, my parents converted to Christianity. In middle and high school, I identified as an Evangelical Christian. In college, I was an atheist-leaning agnostic, though I attended a Friday night bible study because the families who hosted always made dinner, and I was sick of the dining hall. The summer after I graduated, I lived alone in Japan for a few months, and as a result, became a wonky sort of Catholic. Currently, I’m still a Catholic, though the longer I learn about this church I’ve chosen, the more I realize I am of the “cafeteria” variety, with a healthy dose of Shinto-informed animism thrown in.

I am not a Biblical scholar or theologian, but a woman who has always been interested in women in the Bible and the ways that they can act as a dialogue, a window onto a different question or thought tangled up inside of my faith and myself. In the case of Eve, this question is one of hunger and the ways it has been essentially tied to womanhood.

God says to Eve upon her departure, “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you,” but when I read this, I see instead the curse in abbreviation: Your desire will rule over you . (Genesis 2:16) Eve is cursed with desire bound together with her hunger, as if to say the punishment for wanting is to keep wanting. In this way, ideas of desire and hunger, propriety and sin become tied together.

I find myself reflecting on other women depicted as monstrous for their hunger; Pandora and her box, Snow White and her apple. The appearance of lacking desire goes beyond the bounds of etiquette or being ‘ladylike’ and instead crosses into the realm of a moral imperative. Which is to say, a just, good, decent woman is a woman who is free of any type of hunger, be it physical hunger for food, hunger as desire, or hunger as ambition. Conversely, a woman sickened with sin is one who is riddled with said hungers, reduced to a gaping mouth never satisfied.

On a logical level, I can write these words and know they are untrue, that women should be able to want with ferocity or timidity without it bearing on their worth as human. But on a more instinctive, gut level, I cannot shake this twining logic in which I’ve become ensnared. I think back to middle school, those bud-blushed days of early puberty—the knowing that I could no longer rest in the relative ease of childhood—now beginning to bear all the weight and wanting I’d come to associate with womanhood.

I tried so very hard to quell all of my hungers: for attention, to be gazed at, for adulthood—confusing in its juxtaposition for my hunger to remain a child. I tried to quiet a clamoring hunger to belong, to be a friend in the most tantalizing casual way the other children related with each other. I memorized worship songs like exorcising hymns and begged my parents for a purity ring, convinced that the blonde-blue-eyed church-going girls would befriend me in an act of charity, and that their cardboard company would keep me from a nascent sexual appetite. I went to youth group. I pretended I enjoyed mini-golf and frisbee even though somehow someone always “accidentally” hit me in the face. I attended church camp in the furthest northern corner of Michigan, even working in the camp kitchens through high school, my teeth stretched into a rictus of a smile as I attempted to quash the heel-dragging discontent I felt lying in the bunks at night, everyone else snoring around me.

I wanted love, devotion, lust. I was hungry for eyes on me, hungry to be approved of, hungry to be powerful, exceptional, beautiful, all the while fearing that these hungers made me unnatural and beastly, exactly what should not be loved or desired. I felt feverish in how much I wanted, and feverish in how much I feared these wants would doom me in the same way it did Eve.

All the while, I knew deep within myself that I could not convincingly hide the ravening; these twin convictions of unbelonging and pining, effortless and looming. My hunger was becoming wild and unwieldy. I wanted constantly. Whether it was the simple fantasy of strolling into a donut shop and asking for one of everything (how I’ve always wanted to do this!), or the gnarled insistent burning for a body to swell and push against, I carried the hunger, the desire, the longing with me wherever I went. The truth is, I hold it still. There is a part of me, even after so many iterations of faith and years of living in an adult body, that is waiting for punishment, waiting to be banished from the Garden.

*

There is a prayer in the Catholic faith, commonly said after the completion of the rosary, wherein the person praying refers to the faithful as “poor, banished children of Eve.” As I grow older, I feel more and more intensely that I dislike this phrase, or at least do not identify with it. I am a matter-of-fact daughter of Eve: in Eve and in her appetite, I find a lineage for my faith and my hunger, a way to hold two things I have been told live in opposition if one is a woman.

Though I still live with desire uneasily, not quite allowing it to attach itself to my body, perhaps one day I will inhabit it as Eve once did: acquiescing to it, punished, and yet still the Mother of Humanity. Perhaps what I have been told about hungerless women and our sin will prove itself wrong. Perhaps the scrabbling animal thing I have long held off will soften, feathering, an amber-purple fist throbbing in my gullet.