Columns Memory Book

Janet Jackson Helped Me Find My Voice as a Writer

All I knew was that here was this woman who looked like the community I loved and interacted with.

This is Memory Book, a column by Lyndsey Ellis that explores nostalgia at the intersection of race, class, and culture.

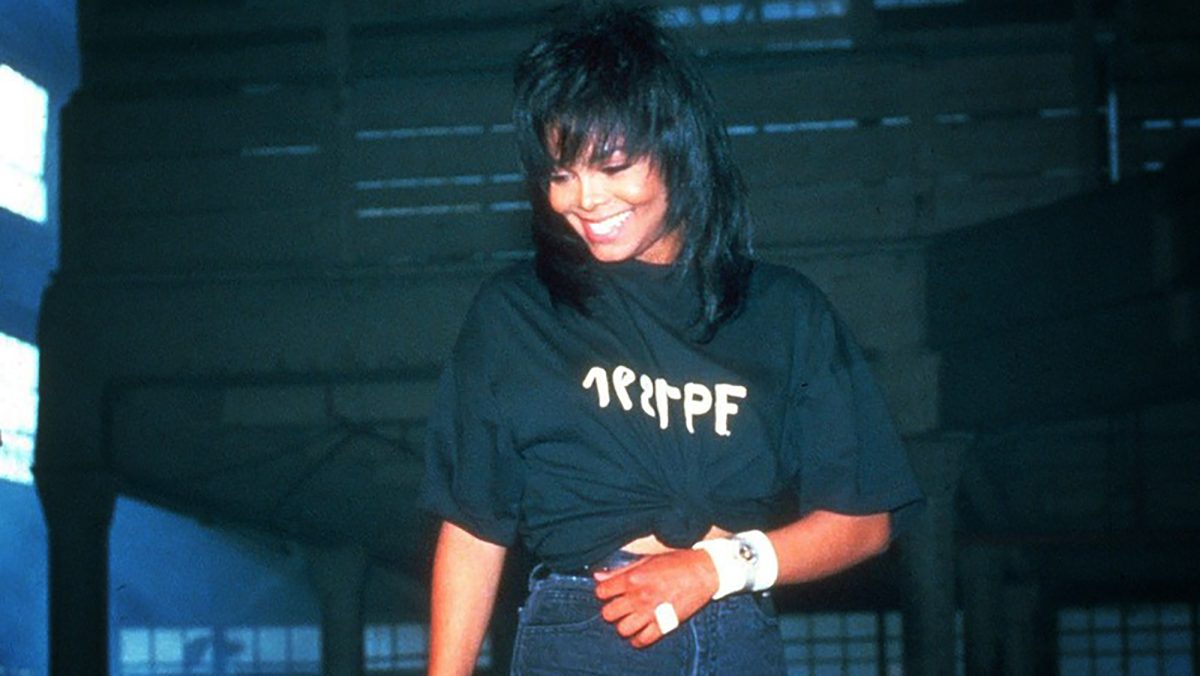

I was a kid, just figuring out the newfound magic of MTV music videos, when Jackson’s “The Pleasure Principle” video appeared on the television screen in the living room. At once, it was like watching someone embody an electrical current. “Look at her go!” I said to my parents. I couldn’t stop grinning as the sound of my own heartbeat pounded through my ears.

At five years old, I didn’t know anything about being a jilted lover as the lyrics in “The Pleasure Principle” suggest. Or that Jackson’s presentation in the video would be celebrated as one of the greatest solo performances in music history.

All I knew was that here was this woman who looked like the community I loved and interacted with. A person who could’ve been an older cousin, an aunt, or my mother, with her radiant smile and the determination in her eyes. Jackson seemed to give her heart and the ultimate sass through the ways she could make her body move. As I watched her transform into lightning from the television in our living room, mouth agape and eyes skittering over her missile-like limbs, she suddenly sprang into that famous backflip of the decade, off a set of speakers in the warehouse loft at the end of the video.

In that moment, watching Jackson soar gave me a hope that surpassed my love for Twix candy bars and Saturday-morning cartoons. I decided that maybe I too could fly and took to practicing my own gymnastics inside the house, although it only led to bruises from failed cartwheels and being chastised for breaking my parents’ furniture.

Since then, after several trial-and-error experiences, I’m learning to transfer the same type of gutsiness and perseverance that I’ve witnessed in Janet Jackson’s artistry to my own work of finding my voice as a Black woman and a fiction writer.

*

Like most Millennials, I grew up on the Jacksons. The most successful Black entertainment family in showbiz had long been a household name, living their lives in the public eye and strongly influencing pop culture. Since “Thriller,” Michael Jackson has forever been in a music category of his own. But the chubby-cheeked starlet with the trademark grin who captured my eye and heart the most was the baby of the famous tribe: Janet Jackson.

I found Jackson during a crucial moment in my life. My parents divorced when I was seven, and it had a drastic effect on me. I was used to seeing the two adults who mattered most in my young life love, respect, and care for each other. Together, they played Gap Band records and hosted large gatherings where the children of their closest friends and I jumped on backyard trampolines and ate cupcakes until our stomachs hurt. They held hands often and made each other laugh a lot. They took tons of Polaroid pictures of their quality time—gardening adventures, piano recitals, Sunday brunches, cinema visits—which I enjoyed looking at to pass the time.

I found Jackson during a crucial moment in my life. My parents’ separation showed me shadows of them that I’d never seen. I witnessed how swiftly a bond so profound and beautiful could shatter and become hopelessly dark. Their hostility toward each other became my anxiety. Their sadness, my frustration. Their uncertainty, my helplessness.

Slowly, I began to retreat, nursing an emptiness that I didn’t understand and couldn’t articulate. Sometimes I felt numb—dead inside with no spirit to experience or process emotion. Other times, I could’ve choked on the waves of feeling that overtook me.

A gaping hole sat on me and kept stretching. The more I tried to communicate and let the world in on my sorrow, the wider that hole became, pulling me deeper into a bottomless defeat. I had recurring nightmares about being stuck, my ankles chained to the floor beneath me. My words ate themselves and stayed lodged in my throat. One minute, I was calm but sulky. The next, I was angry and unable to sit still.

My mom eventually took me to counseling for the night terrors. The sessions helped my growing depressive state, mostly because the therapist encouraged me to find other ways to express myself when I couldn’t talk. He brought journals, and one time he gave me the whole hour to write in them.

I scribbled for a while, spitting out parts of those terrible dreams that haunted me. But the whole act of journaling felt forced—like a rushed performance that I had little energy for—and after a few sessions, the words dried up on me.

And I was confronted with so many things that I didn’t like about myself. My voice was too deep, raspy, and un-girly. I hated looking in the mirror at the space between my two front teeth. The glasses I wore were thick and wide on my face. My feet were several sizes too big for a person my age. The hair on my head was too woolly and unmanageable.

My insecurities made me painfully shy and awkward. The self-doubt chipped away at me every day; I compared myself to everyone at school and in my neighborhood, especially to my best friend at the time who, in my opinion, was the poster girl for charm and beauty. Her good looks and magnetic personality got her everything she wanted, including the attention of my sixth-grade crush. The day I saw them kiss on the playground at recess destroyed what little joy I’d tucked away.

“I just want to be perfect,” I told my mom when she came to pick me up from school that afternoon.

Later in my adult life, it was comforting to learn that Janet Jackson had been open about her own damaged self-worth.

“Like millions of other women, I’ve struggled with low self-esteem my whole life,” she stated in an interview . “I’m doing better in that regard. My inclination toward harsh self-criticism and even self-negation has dramatically eased up.”

Jackson battled a crippling timidity that plagued her childhood and teenage years, and weight gain issues throughout her career. She’s endured sexism and racism in the entertainment industry, which later led to mental health issues, particularly periods of depression.

Jackson’s willingness to show her vulnerability to the world through song was the support I never knew I needed until I found it. The admission of her quest to find inner peace by developing her craft confirmed for me that as a preteen, I’d made the right choice turning from dance to another a rt form that has influenced my personal growth: fiction writing.

I’d collected and devoured enough R. L. Stein and Baby-Sitters Club books to start my own YA home library in my small room between the board games and Lisa Frank folders stacked on the shelf, but I didn’t try my hand at creating stories until my school announced a writing competition. I started developing a thriller about a kid destroying the toxic wallpaper that haunted her family. The idea came to me a few years earlier when I was having the night terrors. I flipped through the old journal my counselor had given me and reread my scribblings, wondering if I could turn those failed attempts at recounting one of the dreams into something more.

The process of developing the plot, characters, dialogue, and visuals was soothing and invigorating. Each day, I’d lie on the daybed in my room when I returned home from school and create whole new worlds filled with superheroines, wizards, goblins, dancers, and dream catchers pouring from my thoughts onto my notepad. I’d tapped into something special. A place within, made just for me to explore my imagination. A place that made me feel as free and uninhibited as dancing to one of my favorite Janet Jackson songs.

To my surprise and delight, the story wound up being a finalist in the competition. Finally, I felt seen, and I knew the craft would stay with me for a while. Writing fiction became a means of survival. Unlike journaling, which forced me to bump into aspects of my life that I didn’t feel fully equipped to express yet, fiction allowed me to put space between the longing to write creatively and the slippery emotions that I warred with. It helped me take scary, uncontrollable aspects in my life—anxiety, isolation, family drama, bad dreams—and transform them into moments that were larger than my struggles and circumstances. It became my way of filling a void that left me wide open and searching for purpose in my life.

*

And now that I’ve adulted in this Black-woman skin of mine, I’ve come to not only respect the depth of vulnerability in Jackson’s music but also her technique—both unique and recognizable. Her style, kaleidoscopic. She’s skilled at bringing forth a balancing act between voice and dance. The former is usually subtle, sultry, and supportive; it nurtures and mirrors a tune rather than overshadowing it. The latter is a stark contrast: piercing, potent, provocative—a stark contrast to her voice’s gentleness.

Writing fiction became a means of survival. I like the way Jackson chooses to ride a song’s beat with her vocals rather than sing over it. This understated approach helped show me the importance of delicacy in my writing. To not run into the defeat of letting words get in the way. That to express more, sometimes I have to say less, chop off the excess that blocks the sentiment I want to convey. I’m learning, on instinct, how to limit myself so the flatness of text can transform into something of a layered experience for the reader.

I’ve continued to write and listen to Jackson’s songs, especially those like “Control,” “You,” “Doesn’t Really Matter,” and “Velvet Rope,” that help me navigate difficult emotions and channel positive energy . Other songs of hers that sound remarkably mystical, like “Escapade” and “Runaway,” compel me to brainstorm and create new worlds. Sometimes, I’ll watch her videos—always innovative and high-energy—which push the limits of my imagination and spark my drive to explore new concepts.

Back in ’87, Jackson ignited something in me before the saying “Black Girl Magic” existed. In that moment, my five-year-old self didn’t see a world-renowned Jackson. I just saw a beautiful, talented young woman who was determined to go for hers in a world that told her she couldn’t.

Jackson’s artistry and her will to overcome adversity has helped guide me to a full appreciation of Black resilience. The same Black resilience that I continue to write about and share with others who’ve found joy inside struggle.