Catapult Alumni

The Pursuit of Perfection

Later on the same trip, we got stuck in a horrendous traffic jam on a large bridge going into a major city. An early September heat wave had descended upon us. By this time, the temperature had unexpectedly swollen to nearly a hundred degrees. Bumper to bumper, the humans’ blaring and honking metallic machines […]

Later on the same trip, we got stuck in a horrendous traffic jam on a large bridge going into a major city. An early September heat wave had descended upon us. By this time, the temperature had unexpectedly swollen to nearly a hundred degrees. Bumper to bumper, the humans’ blaring and honking metallic machines had inched along like grotesque coils of molten chains, their gleaming hoods and dazzling grills morphing into dragons’ maws that sucked in and then exhaled the vicious heat of the sun. Murmurings of angular momentum in the convective zone goaded a shimmering neutrino oscillation, so my man-made muzzle was definitely having major trouble trying to handle the oppressive humidity. As I’ve said before, Canis Lupus Familiaris should never have been given such a truncated nose. It was scary because in a very short span of time, I was well on my way to dying of heat prostration. I gasped and wheezed as overtaxed lungs tried to latch onto the sullen indifferent air. My lolling tongue was floppin’ willy-nilly frantically trying to compensate for my nasal shortcomings, and I was panting hard. Perspiration had nowhere to go, so I was wishin’ and hopin’ that I could grow pores in my skin. The boy shouted to his father that my tongue was beginning to get darker and darker, going from light to deeper hues of purple, so the man told him to take the beer out of the cooler and dump the ice over me. The boy also put the cubes around my throat, but this still didn’t seem to do the trick. So, in an act of desperation, the boy jammed his hand down my throat and took out all the phlegm that had collected there. I coughed and wheezed more violently, but then things suddenly got better, and I realized that the boy had saved my life.

And the journey continued, and I won another show.

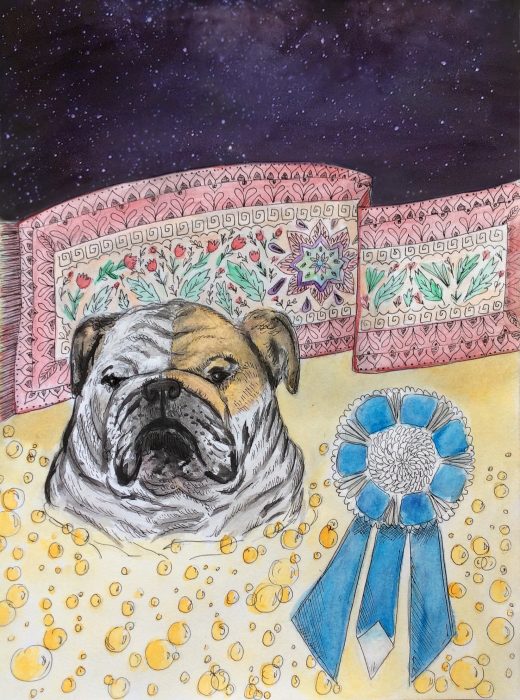

Naturally, the three of us had to celebrate my victory, to say nothing about raising a glass to my survival in this dicey world of ours. In the latest go-round, I won Best of Breed and then had gone on to soundly defeat a Standard Poodle to win the Nonsporting Group competition, but later had lost to a ratty little Affenpinscher in the Best in Show category. Apparently, the judge wanted me to be complex without being complicated, a situation that would appear to defy the laws of reality. But what the hell, it was another case of an apple losing to an orange. I sighed and thought to myself that it couldn’t be helped. Obviously, the judge wasn’t a big fan of brachiocephalic heads. However, this small defeat was pleasantly offset by the boy’s triumph in which he won the Junior Showmanship Competition. Clearly, the kid knew how to show off a dog to the best advantage. His stellar achievement made me feel as if he and I were a good solid team and that each of us was working for the improvement and benefit of the other.

When we got back to the motel, the man and the boy turned on the TV and drank beer till late. The boy opened up one of the suitcases to look at the growing collection of blue ribbons that I had won on this campaign. I watched him closely while he stared carefully into the ornate rosette centers of each one as if to see if he could discern my formula for my success.

Turning to me he said, “Hector, you’ve accomplished so much in so little time. I wish I could make the same claim. The patterns of these prizes remind me of a stained glass window in a church that I go by when the bus takes me to school.”

I gave him my best version of a canine smile. Yes, it was true — winning was a kind of religious experience. Basking in this thought, I jumped up into the big overstuffed chair that was near to the window. The kid was making me feel slightly human, so I figured it might be a good time to be on the same level.

He told me this dog show business was such a great adventure for him because he was getting to be away from school, and he was practicing how to be an adult. Drinking beer was part of the program. He told me that his father called the hooky from school thing an “educational experience.”

Then the boy led me out to the balcony, and we watched the stars. The Milky Way was especially spectacular and inviting on this auspicious night, prompting the boy to say that the world was so brand new to him, and he correctly guessed that it wasn’t so new to me.

“Hector, you’re a man of the world. Your former owner told me as much. I want to be a man of the world too. And school is what’s holding me back.”

I laughed to myself because he was all of ten years old. And like so many ten year olds, he couldn’t stay on topic for very long, so he went and changed the subject. He wanted to know all about my forebears, and I wished I could have told him; however, he more than made up for our communication barrier by telling me all about the horrible stuff he’d been reading regarding the history of my tribe. And I have to say, when he told me chapter and verse what had gone down, he was pretty close to being 100% accurate.

“Gee Hec, your kind were the ultimate outsiders. I actually have a rough time wrapping my head around that one as I try to imagine what it must have been like having to chase after enraged bulls and latch onto their noses. At the end of the day, your breed must have felt happy if they’d won. Hell, just being alive to think and feel would have been proof of that, but even if they were happy, they must have also felt sad that that was their only purpose. Everyone’s got to have some kind of purpose. And hopefully, that purpose ought to be a good one. But there’s no way in hell that running after bulls and trying to kill them is a good purpose. It must have been a little bit like what it was for gladiators in the Coliseum — they got to be dead before they were actually dead.”

He rambled on about purposes. Then the boy remembered the part about how bull baiting made the meat much tenderer, and he said that as purposes go, that was such an awful purpose and why in the world couldn’t they think of a better reason for existing?

Sipping from his beer, he repeated, “Your kind must have felt like total outsiders.”

He paused to punctuate his thoughts and took a long gulp. He smacked his lips and remarked, “Ah, that’s so refreshing! Dad says it’s perfect for the summertime.”

Relishing the effervescent brew, he told me that he knew what it was like to be an outsider. “So Hector, when I go to public school, the kids laugh at me. They tell me my father is a crackpot weirdo who runs a school for emotionally disturbed kids — in other words, they’re just plain wacky as bed bugs, one step away from the big-ass bumper crop booby hatch. They razz me and lord it over me, saying that all their parents think my dad is some kind of egghead crazy man who is so weird that he couldn’t even get a loan from the bank to start his school, and he doesn’t even call his loony bin an actual school. Instead, he calls it a ‘residential treatment center for young boys.’ I mean, he makes it sound like it’s some sort of creepy hospital where you never know quite exactly what in the hell is goin’ on. My classmates aren’t buyin’ it. They say there must be some weird experiments goin’ on there at the Charwood School for Boys. They tell me that in those kinds of creepy places, doctors attach electrodes to people’s heads and give ’em shock treatment, and afterwards the patients turn into voodoo zombies. If that hack job procedure doesn’t pan out, then they go the more invasive route and slice into the brain itself, goin’ whole-hog into the lobotomy thing, whackin’ and hackin’ away at the prefrontal lobes. My classmates continue to razz me, and then they rub it in some more by walkin’ around the jungle gym all stiff-armed and goggle-eyed, tryin’ their damnedest to look like Frankenstein, Werewolf, and Dracula monsters. They say, ‘Welcome to Albert’s House of Autism and Ambulatory Schizophrenia. We hope you’re havin’ a good time.’ They tell me that’s where I must be comin’ from. They say I’m a goofy spazz and one of the weirdos. And they yell at me saying that there are no wacky kids in my public school except for me. In fact, there are no wacky kids in this entire state because my classmates have it on the good authority of their parents that that was what the bank officer told my father when he turned him down for a loan. And ha, ha, ha! Isn’t that a total barrel of laughs? Yes, Hector. That’s what they tell me over and over again. You see Hec, it’s like this — I’m spending the better part of my childhood surrounded by insane children. Thank God none of it will rub off on me.”

I nodded to him and looked up at the moon. He slurped on the last dregs of the can and crumpled it in his fist. I could tell by his expression that this action had somehow given him a sense of accomplishment because the next thing I knew he was tapping the distorted hunk of tin with his index finger. He did this for a while, watching it teeter-tooter back and forth making metallic noises. I could tell that the kid was savoring the suds. The tinglings of a newfound ecstasy were matching up with the real world. He gave me a nervous grin. Then, he abruptly cracked open another Bud, giving the coarse hair on my shoulders a long pet as we gazed deeply into the heart of the starry night. I took note that anomalous Cepheids in a distant galaxy were well on their way to attaining maximum luminosity, and a blue straggler in RS Puppis was significantly brighter than usual. I was no fool. I was a dog, and I knew what was up. I thought about how the humans might have wanted to know this information, but then it occurred to me that they never ask me. So, I deliberately let the astronomy thing slip my mind. Besides, I had other stuff to do. Searching persistently for whatever breezes that the evening had to offer, my truncated nose did an astral dance. As the boy turned up the overhead fan a notch or two, I looked back at him and perked up my dappled ears — he had the look of a tethered bull. The nervous grin lingered for a while and did not seem to go away entirely. I narrowed my stare to search further down the gathering frown, thinking “Oh, my poor little human being. How I wish I could help you.” For the rest of the night, I nearly worried my brachiocephalic head off thinking about his problems.

When we got back from dog shows, the partying would continue, albeit a bit more sporadically. This became part of the routine — the man would finish work at the school and would take me and the boy to a bar where he would drink beer and Old Grand Dad and order Coca Cola in large frosted mugs for the boy to enjoy.

On one occasion, the man sat back on the bench of the middle booth on the right and praised the wonders of modern technology that could produce such intensely cold glass containers. He indicated that Freon might have something to do with it. As if that were not enough, he noted that modern ingenuity could also present “video tape replays” which made it possible to see a play on the gridiron and then see it again seconds later. To emphasize this point, he gestured to the grainy black and white TV set nestled in the upper corner of over the far end of the bar. At that very moment, it was playing back a spectacular long bomb touchdown pass as the patrons erupted into frenzied applause. The man said, “How cool is that.” The man also said that a major selling point of the Magnavox TV set was the fine walnut cabinetry that framed it snugly in the corner right below ceiling and wall. All of these things — the cabinetry, the replay, and the technique of frosting glasses — were wondrous examples of human ingenuity and the quest for perfection. And he explained to the boy that it was exactly this search for meaning that was the reason why he was in the bulldog breeding and showing game because anyone could see that no one ever got into this game to get rich. Oh no, if they did, they would be destined for a colossal case of disappointment.

The reason for this was that the quest for perfection was a long and circuitous road, one that was fraught with many obstacles.

Turning to the boy, he said, “Albert, you know that old rug we have which is spread out on the floor back at the apartment?”

“Why yes, of course. I think it’s one of the best things in the room. I really like it a lot. Hector likes it a lot too. Every time he goes in the room, he wants to make himself comfortable and stretch out on it. Most likely, he’s inspired by the intricate design that mimics the bountiful complexity of life.”

“Yeah, he’s no fool. And you and he aren’t the only ones. I like it too. But Albert, I wanted to ask you a question.”

“Of course Dad, ask me a question. Fire away.”

“Have you ever noticed something odd about the design of the rug that each of us sees on a daily basis?”

“No, there’s nothing odd. It’s just plain beautiful.”

“Oh it’s beautiful alright. But there’s so much more than beauty.”

The man milked the pause for all it was worth.

Finally, the boy broke the spell. “What’s that, Dad? Don’t keep me in suspense like the video tape replay machine.”

“The thing about our family rug is that the design is absolutely symmetrical and perfect except for one little mistake. And the makers of those rugs use this notion as part of their design. They deliberately put in a very small mistake.”

“Really? If that’s true, then tell me where the mistake is.”

“It’s in the upper right hand corner on the side that’s closest to the living room window.”

“No kidding?”

“Absolutely no kidding. Look at it sometime when we get back to the house. Probably that’s the reason why Hector never sleeps on that side. He likes to crash out on the side of perfection.”

The boy seemed thunderstruck. “You mean the rug makers make a mistake on purpose?” They do it just because they can?”

“Damn right they do. They do it that way to let you know that perfection is supposed to be impossible. They do that to let you understand that only God is supposed to be infallible and perfect. Everything and everyone else is imperfect.”

“Wow. That’s too ridiculous. I don’t understand why they would go to all the trouble to make it almost perfect. I mean, if you’re gonna go that far, you might as well go whole-hog and finish the damn job. Like the beer commercial says, ‘Go for the gusto.’”

“Well Son, I’m so glad to hear you say it. None of that godawful God bullshit. There isn’t any God. There are only goddesses. They’re the ones in charge, and the world is imperfect because of it. So, while we’re at it, you and I might as well try to attain perfection in whatever small way that we can.”

“How in the world can we do that?”

“We can do that by tryin’ to make the perfect bulldog. Albert, there’s nothing to stop us. You and I can do it. It’s my dream. Maybe someday soon it’ll be your dream too. I sure hope so. C’mon, Son. Let’s you and me think big.”

“Damn right we will, Dad. I wanna think that way. But you gotta show me how.”

“I’ll show you the way, Albert. I promise I won’t let you down.”

He explained to his son that he wanted to build his own dog show kennel and to have a quality stable of stars like young Hector and that the foundation for this perfection would be comprised of Hec and the right combination of beautiful female bulldogs. Building a quality kennel, he explained, was easier said than done. But according to him, the thing to remember was the notion that females must be the bedrock foundation of the entire enterprise.

As if to underscore this point, he said, “Albert, a dog breeder can always buy sperm. However, getting quality females is the greater objective. That’s where it’s at. Now that we’ve got a great male, namely young Hector here, that’s going to be my long-range plan. Hec is about as good as it gets, and we were truly lucky to acquire him. Look at all the shows he’s winnin’. He’s freakin’ awesome.”

From the perspective of the floor, I looked at the mirror over the bar and saw my reflection. Buying sperm? I guess that might involve me. I would become a conscientious contributor to the common good.

After a brief twinge of narcissism, I stared at the fine walnut cabinetry and knew that someday it would be out on the curb awaiting pick up from the trash truck. How perfect was that? Then I paused to look at the plastic clock just off to the right, which bore the trademark of a local premium draft beer. The pendulums for this device were two miniature beer mugs that would toast each other as the seconds ticked by. I liked it that the mirth making seemed to go on for perpetuity — or at least as long as the mugs continued to come together.

The owner of the bar was Louie, a stout little Greek man who was familiar with the man and his son and considered them to be regulars. His was an establishment that had no problem with letting dogs like myself onto the premises. The fat little guy indicated that dogs had some sort of special wisdom that couldn’t be codified or comprehended and that their mere presence was cause for a nebulous but important jubilation. Of course, he was right, but I didn’t have the ability to concur. It was so much fun lying there, curled up on the floor, listening to the man and the boy talk about dog shows, perfection, and the meaning of life. Then the man and the boy shifted gears and talked about women, although, as you might expect, it was the man who did most of the talking.

Midway through this train of thought, he took a sip of Old Grand Dad, which led him deeper into the philosophical mood that he was in.

Then he jiggled the ice at the bottom of the glass and said, “Look Albert. Look around the room. This is our preserve, our kingdom of paradise, our realm. We rule the roost. We’re top of the pops. Remember when Mom brought those brownies to you for dessert tonight? I was so glad you turned them down.”

“Why? It was no big deal. I turned them down because I was full. There was too much food. I was only tryin’ to be polite.”

“Yeah, that’s good. I have no problem with that. Amen for manners. But understand that all that sugary business — that’s what women are into. They adore that stuff. I mean, they lap it up. In fact, they slurp it and go googly-woogly. Watch ’em sometime. They’re like little schoolgirls in black tights and plaid skirts. They’ll be practically goin’ goo-goo-gah-gah over some slice of red velvet or a plate of peach cobbler or a portion of cheese cake or you name it, if it’s in the category of sugary confections, they’ll be actin’ silly and bendin’ over backwards to get their fair share of it. But we’re men. We don’t go in for that shallow feckless frivolity. It just ain’t masculine. That’s the reason why I started you drinkin’ beer. It’s one of the things a man does. I want you to understand the feelings associated with it ’cause I sure as hell don’t want those feelings surprising you later on down the line. As your Dad, I have to keep track of these things because I don’t want you to get crazy like the kids in the school. Comprehend this — I don’t want you to become emotionally disturbed. It’s the reason why I forbid you to watch certain TV shows and movies like that James Bond secret agent bullshit. I don’t want you to grow up to be a mean person, and those movies and shows have too many mean and dastardly people. And I don’t want any of that stuff rubbin’ off on you, ya hear? I’ll have you know that you have a lot of responsibility.”

“Dad, I have responsibility? I thought I was busy being a kid.”

“Those things aren’t mutually exclusive, Albert.”

“Explain this to me, Dad. Because if I have responsibilities, I sure wouldn’t want to be remiss…”

“Remiss — what are you doin’ using such high-minded words?”

“It’s a new one that I had to learn for Mrs. Hoyt’s English quiz that she gave me last week.”

“Good. I hope you got it right.”

“Yeah, I did. In fact, I aced the whole thing. Only problem is, school doesn’t amount to a damn. It’s an exercise in spittin’ back trivia to those who want to hear it. They never get bored with makin’ me jump through hoops. Every day I feel like a trained seal who’s flappin’ his flippers and balancin’ somethin’ on his nose. I don’t know why in the world I keep walkin’ back to the dead end every day. Goin’ to dog shows is where it’s at. But Dad, why is it that you can get off the topic, and I’m not allowed?”

“Son, you may have a point there. I’ll try to stay on point.”

“So lemme get this straight. If I don’t know anything about these responsibilities that you speak of, then maybe I wouldn’t be able to live up to them, and I sure wouldn’t want that to happen.”

I squirmed on the floor and adjusted my position a bit before listening more closely.

The man continued as he ordered another beer from Louie. “I’ll put the matter in perspective, Albert. It’s about the special school. This will be your big responsibility. As my son, you have to be a sterling example for the kids who are being treated there. You have to be a good role model. It’s part and parcel of their long-range therapeutic plan. I’ve actually discussed this at great length with the psychologists who are my consultants. They loved the concept. And they told me it’s a variation on the old classic of learning by doing. They said that the kids at Charwood School for Boys need to have a blueprint for sane living within the context of a residential treatment center. And Albert, in case you don’t know it, you are that very blueprint. You are a supremely sane person. The shrinks nominated you for the position. You passed with flyin’ colors. They think it’s a great idea and so do I. Doesn’t it feel good? Reach out and celebrate it. Let it sink into your psyche. Let it saturate and simmer there. Remember that when you’re around the kids in the school, you’re the sanest person in the room. Doesn’t if feel like you’re on a baseball team that six runs in the lead? Doesn’t it feel as if you have a huge head start?”

“Yes Dad, it feels great. I can’t tell you how great it feels. My head feels big, bigger than life. It’s right darn brachiocephalic, just like Hector’s massive skull that helps him to win so many dogs shows. The cranium just keeps on creatin’. I’m in the lead, and I’ll never let go. I’ll never fall behind ’cause you’re steerin’ me in the right direction. I feel so darned safe and secure. As a matter of fact, I think I’m feeling the beginnings of perfection. It’s a wonderful emotion.”

“It’s good havin’ so much responsibility because then you have a blueprint too, a way for tryin’ to achieve perfection.”

Again, I shifted my position of the floor and flirted with the canine gods of sleep, thinking that might have been a good retreat. My consciousness was lulled into a deep sense of deja vu because I correctly noted that it had been in establishments like this that dogs shows originally blossomed and bloomed into the world, which naturally made me feel right at home. And in the course of events at this friendly neighborhood establishment, a well-tempered ecstasy reigned supreme.

Then the pay phone in the corner rang and two or three of the customers turned to Louie and said, “Tell her I’m not here,” and Louie, being a nice obliging fellow, told a big fat fib for the benefit of the guys, and peace and tranquility prevailed, accompanied by country and western music, big band jazz, and the latest rock and roll hits from the juke box. At that moment, I knew the real news. Far into the future I would savor this time, understanding full well that I would associate this barroom visit, and others like it, with sporting events which were so much better than the grotesque abominations practiced on my ancestors.

I would also link these visits to long sessions of music that emanated from their jukes. Songs and verses became sanctified, causing me to nudge closer to the source of the sound that was holding me spellbound. My dappled ears perked up and danced when a baritone sax burped like a bullfrog. It provoked a sprawling modulation from a clinking piano that set free an ancient blues riff filled with pain and peril, which in turn gave shape to a crepuscular enchantment within the silvery verse and chorus system that was driving the tune. I reveled and admired the melodic human voice and the acrobatics it could do. I was especially impressed with the way the superior beings could bend a note, and after they modelled it into a curve, they could make it waver and warble too, so it appeared to hover in the air. I would have stood back and solemnly saluted if I had had an elbow to make it happen. Ah perfection! I could practically feel it wafting through the room. At that moment, I yearned for a voice. If I could claim one, what a yell I would have bellowed, and if I possessed the elbow and vocals in tandem, what a drummer I might have been, rumbling and crashing from behind the kit, creating a lustrous cacophony for the humans to hear, an alternative to the one that the boy’s father was proposing. I imagined it all. In this ideal situation, the song was sure to be my plaything, and I could slide under its skin to make it travel in whatever direction the moment made up on the spot. The kids in the special school were certain to be pleased.

Notwithstanding my apparent canine shortcomings, however, I still enjoyed the violins, trumpets, and saxophones, which provided a lush background, prompting me to observe that ultimately I had a huge advantage over these superior beings — I could hear things they could not. Many was the time when I wished I could have let them know, “You don’t know what you’re missin’.”

But I suppose these new insights were neither here nor there because on a subsequent barroom session, things got dicey — the man and the boy got into a minor tiff because as the man drank more beer and chased it with a few shots of Old Grand Dad, he became argumentative and laughed at the music of the boy’s generation, calling attention to a perceived lack of musicianship.

“Ha, do you hear that right there? The piano player’s goin’ Da, Da, Da, Da, Da. The guy’s really improvising now, isn’t he? Cat’s got delusions of grandeur ’cause he’s under the mistaken impression that he has the song in the palm of his hand. But I can hear him fumblin’. My ears don’t lie.”

He pointed to his ears. I twitched my dappled ones.

“Dad, it’s called a pedal-point bass line. It’s pretty standard stuff if you wanna know the truth. Some people like it when the chords flex their muscles that way. Johann Sebastian liked it, and he was probably onto somethin’ big.”

“I think he needs to take more lessons. That’s what I think, if you wanna know my opinion.”

And the boy really did want to know his opinion, and for that matter, so did I even if the boy and I would sometimes want to disagree with it. And later on, the boy told me that in spite of all the unhappiness that was happening at school, he truly worshipped his father and knew that he was a good man. But the boy was also old enough to understand that his father was a flawed man too. Perhaps that was reason why there was such a need for all this tough talk about perfection?

The boy sipped from his extra-large Royal Crown Cola.

His father looked at him, narrowed his eyes into an expression of extreme seriousness, and said, “Son, the kids in the residential treatment center have had really hard lives. Nothing in their existence has been easy. For them, austerity, adversity, and punishment have prevailed. I think it’s very important that you understand that.”

“Sure I get it, Dad.”

“Yeah, you get it, but like everything else in life, there are levels of gettin’ it. What you probably don’t get is that you should always always give them the benefit of the doubt because they’ve had a rougher time of it than you have. Will you promise me this, Albert?”

“Oh of course I will, Dad. You know I think you’re the best.”

And the boy would later confide to me that he knew his Dad was the best. In fact, his dad was so amazing that he couldn’t quite understand why he hadn’t been elected President of the United States already and why hadn’t he won the freakin’ Nobel Peace Prize for cryin’ out loud?

I squirmed on the floor. Again.

But the best episode that occurred on these sojourns to the bar was when, upon leaving the place, the man had to urgently answer the call of Nature as the three of us were all walking back to the car. It was fairly late, and there wasn’t a soul around, so the man decided that it was totally safe to relieve himself. As luck would have it, our car was parked directly in front of the bank whose officer had denied him a loan to start his school. The man remarked that he would never forget the coldness that lingered in the heartless bastard’s eyes. He also said that awful humiliating experience had provoked a rage in him that would never die, and someday he would show the loser of a bank officer that his special school, the Charwood School for Boys, which was his pride and joy creation in this whole wide world, would have been abundantly worthy of that pompous jerk’s money-grubbing loan. The man let his fantasies run wild, blurting them out loudly, saying that sometime in the future, the bank officer would fall on hard times, so the skinflint officer would wind up begging him for a very important favor, and the man would be able to take exquisite delight in turning him down. The man said that when that time arrived, he would love to see the disconsolate look of the groveling bank officer’s face. Then he would be able to file this away in his memory, so he could revel in it whenever he was feeling down. And when he did that, he would feel happy again. A substratum sensory field would sprout a bewitching effigy. Then people would stand to attention and take notice. Then the effigy would burn into a spectacular incandescent conflagration and something strange and beautiful within him would shiver and be satisfied.

Accordingly, as the boy and I looked on, the man hastily unzipped and proceeded to empty his bladder on the steps of the bank. I watched in amazement as rivulets trickled down grooves between bricks, pooling rapidly into an expansive puddle near the curb. The advance edge of the liquid lurched forward into the culvert and disappeared.

“Dad, what are you doing?” the boy exclaimed, staring in agog disbelief at the ever-widening deluge.

As a dog, I wondered for a second about whether he might be marking out a new patch of territory to claim as his very own, but then I remembered that superior beings don’t do it that way.

“Don’t interrupt me, son. Can’t ya see I’m having a perfect moment? I do believe deep down in my heart and soul that I’m havin’ a religious experience.”

And I could tell that he was.

Then the man began to have some problems with his wife. I surmised that the reason for this was that more and more, in his mind, the dog show business was starting to eclipse and overtake the business of real life. Real life was struggling to keep up. It would appear that my winning ways at the dog shows had made him feel as though any gathering joy that he might have the chance to experience was well within reach of possibility. I felt proud to have been of service. Indeed, many was the time when the boy and I would see him walk down the street and break into an impromptu giddy gait at the omnipotent thoughts that were running unchecked and ricocheting inside of his human head. Since I’m a dog, I am well versed in detecting the nuances of these moods. By contrast, everything else in the man’s life took on shades of dismal melancholia. For him, the day-to-day was becoming gray. That’s the problem with the mundane. It steeps and it staggers. And make no mistake — I am well acquainted with this steepin’ and staggerin’: you will of course recall that I spent considerable time cooped up in a dreary backyard. However, the big difference between the man’s problem and my problem was that I didn’t have a wife, and the man did. That meant he actually had to pay attention to her feelings, and for some men of the superior tribe, that’s a very tall order. They just can’t seem to get the hang of it.

The first time I noticed that he was having a rough time paying attention to her feelings was when she came back from the grocery store with a load of supplies for the school. From my perch at the side window of the apartment, I could see her toting the bags up the long steps that led to the back door. On entering the doorway that led to the kitchen, she proceeded to unload her burden. I walked into the kitchen to watch her. Then she had to go back for a second and a third trip. My nose discerned a hint of sweat from her brow as I duly noted the arduousness of the task at hand.

Upon retrieving the last of the bags from the car, she paused to rest, at which point the man, who had all this time been in another end of the apartment, entered the kitchen.

“Helen, did you get catsup?”

“Oh, I’m so sorry. I forgot. I’ll get it next time.”

The man suddenly paced back in forth, and I could tell that a rage was gathering within him. The pacing got faster and more erratic. He went to the cupboard above the sink and opened the door.

“Helen,” he said. “I want there to be catsup in here at all times. Do you hear me?”

Then he slammed the cupboard door before going over to the table and hitting the tabletop with a glancing blow.

“Just remember, Helen. In this business we have here, you’re a mere taxi driver. And that’s all you are — a common gofer. You fetch things. That’s your gig. Do your damned gig. It’s a division of labor. Do you understand? I’m the one with the degree. Always remember — you only have a high school education.”

“But I’m the one who worked as a secretary, so you could get the degree, so we could have the business.”

“That’s neither here nor there. You’re off the topic. I know this may be hard for you, but try to stay focused and in sync. Just be sure that from now on, there’s plenty of catsup in that cupboard. I want you to make a concerted effort. Burn it and brand it into your brain. Singe it and sign it into your synapses. Do you hear me, Helen?”

As he was saying this, he was smacking the cupboard door with the palm of his hand. I winced and shuddered at the sound.

Then the lady did something rather unexpected. She didn’t answer right away. She went to the bags of groceries that she had brought in from the car and started to remove the bottles and food items. With a look of complete calm on her face, she proceeded to throw them onto the floor. Sometimes she even wound up like a baseball pitcher as she hurled them onto the floor with all of her might. Any fool could see that she was heavin’ toward the strike zone. I saw the muscles in her forearm that were tellin’ me it was true.

In a matter of seconds, the cacophony of breakage became too much for my dappled ears to endure. I retreated to the living room, but could still hear the devastation loud and clear. Correction — loudly and clearly. Adverbs modifying how I heard.

The boy and his sister rushed to the kitchen, and the man greeted them, saying, “I want you to know that your mother is having a nervous breakdown. She’s having a psychotic episode.”

His voice struggled to be heard, competing with the din of crashing orange juice bottles, spilling milk, thudding frozen meat, bruised fruit, and rolling cans of zesty tomato and beef and barley soup. The lady never said a word throughout the entire incident — she seemed hell bent on letting the groceries do the talking for her. I ran back to the kitchen. The floor was a mosaic of colors comprised of smashed glass, ruptured plastic, leaking dairy containers, dented tins of spam, and ruined vegetable produce.

I didn’t stick around for the man to say he was sorry. Maybe he would. Maybe he wouldn’t.

I wanted to retreat to the living room to lie down on the almost perfect rug, but the boy took me to the kennel and whispered in my dappled ear. He said he wished he could become a dog, so he could win at shows and parade about in a majestic manner. People would clap. Then the boy could collect blue ribbons with charmingly intricate rosette designs that really and truly meant something.