Catapult Alumni Nonfiction

On Not Being Bipolar

Perhaps the world did understand me, if only in that I felt broken and psychiatry agreed I was.

I am a woman who fully identified with the label Bipolar for almost 20 years. Early on, I was given no other language to understand the altered states and despair I experienced besides disease and chemistry. When I look back on the very recent past, I see that I used the identity of Bipolar like a brace around my mind, to hold it still, to teach it where it could go–where I could expect it to be at any given moment. There were books written about it I could read, when I could read, and there were rules–patterns. I understood myself as a woman who had extreme mood swings. A woman who heard voices and saw things, which were realities with no meaning other than illness. I was a woman who needed drugs. I was a woman who would never heal. “There is no cure,” was something I heard often. It’s something I heard at 21. It’s something I heard many, many times afterward.

And perhaps the word Bipolar saved me for a time. It did a few things for me. It got me medical care. It got me the kind of care that our society has to offer for what I experienced. It drew doctors to me, doctors with tools to ease my pain — in a way. And even, it drew validation of my suffering. Yes, you are in more pain than most. Yes, everything is too hard. And it didn’t seem so for everyone. Yes, your emotional pain feels wrong and we think it’s wrong, too. Yes, your pain is real. So real. It was corroborated, by people with degrees and authority.

Perhaps the world did understand me, if only in that I felt broken and they agreed that I was. I was different. The diagnosis and the drugs allowed me the understanding that my suffering was beyond my control…such a relief. And, despite that I no longer ascribe to this identity, this is still true for me, just in a different way–In that resistance is the problem. That the idea of control is an illusion far too often enforced upon us.

Bipolar was a map. It was scaffolding on a building, it was a straight hallway to walk in a maze of a mind. There were numbers that insurance companies understood. There were instructions, that if I didn’t think too much about, were at least something I could do besides lay in bed, besides grasp my head, or stare down a bottle of pills trying not to die. It was hope– something that maybe my friends and family could use to explain me, explain my anger, explain why I would call in the middle of the night and beg to come over to hide, to avoid my psychiatrist and the hospital. I was Bipolar. At least that made sense. At least, if only that, made sense.

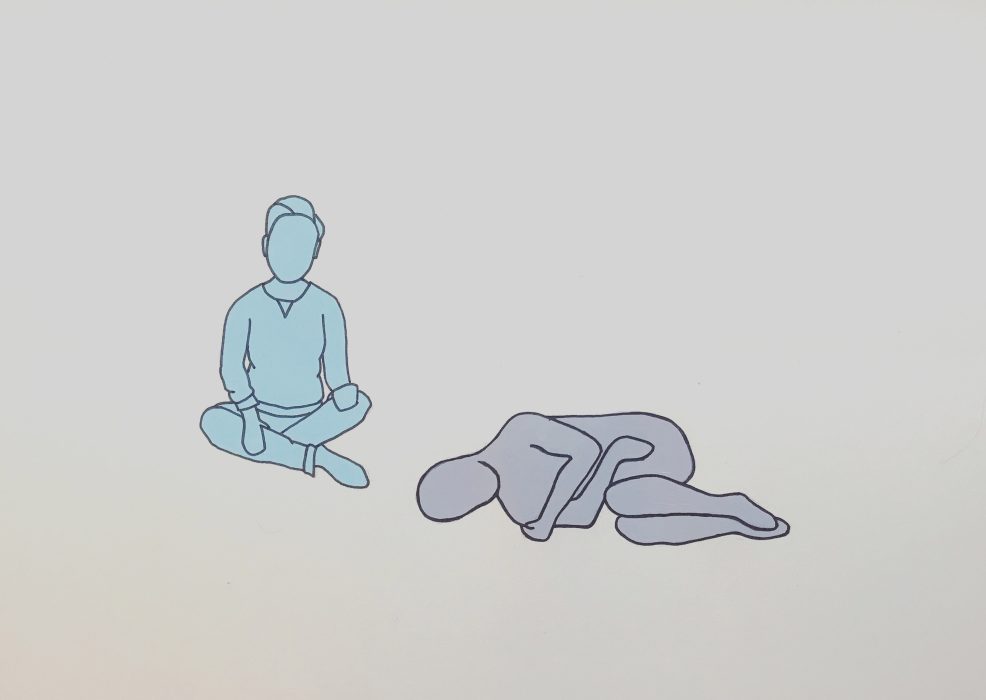

It helped me. And it helped them. It did. Until underneath it all I started to see that in those hallways, behind those walls and braces, with those directions and instructions–I had nothing. No power. No choice. My mind would not wander anywhere ambiguous, like when it did it was in some dark alley, afraid of attack. My mind was afraid of itself. I had nothing but illness and most importantly, I had no path to healing, Bipolar was incurable.

I was done for. All the studies said, I would die, I would die soon, and I would suffer till then. Either from the drugs and their effects on my body, from the lack–the lack of feeling, the lack of choice, which was perhaps the actual things that would help me heal. All the studies said I would die. All the stories said I would die – or disintegrate. Disappear somehow, in some uncertain circumstance where everyone I loved would wonder – was it their fault? Did they not try hard enough? Did I not try hard enough?

I would die Bipolar. I would die on drugs. And I woke up to this as I looked closer at the rules. What I was told was the way it was. The reality I was meant to swallow. The pills I was meant to swallow. Everything I was meant to believe about myself. I started to look at my mind, my dreams – my visions – my voices and my suffering–especially my suffering–without fear or rules or braces, and these parts of myself spoke to me of a path to healing.

I listened to my mind as it tenderly wandered off the paths laid out for me. Oh, yes, I was afraid. The depth of my sorrows have always been great. The confusion has always been crushing. Before I fell into sedation, even while I was in that ocean of chemicals, all the while, everything was still so massive and confusing. Every little bit of it didn’t make sense. No sense at all. And it hurt. It was painful. Every inch my mind wandered. Every door I opened labeled disease – Every door labeled ‘danger’.

Every step was fraught with fear. Will I be abducted, drugged, gaslighted, coerced, imprisoned if I take a wrong step? But I had so many doubts about this framework handed me called Bipolar–this map–their certainty, and rules about me. Some part of me knew they were wrong. So I kept stepping out of line. Way out of line. Each time I wondered if I could do it. If I could be ok without these rules, these drugs and doctors.

As I was slowly stepping off the final of 5 drugs, one of my best, oldest friends said to me on the phone that my voice had changed. She said, “I feel like I am talking to another person. I mean it’s you,” she said. “But, now, it’s really you”. And we cried together because it felt like I was finally free. In a way I was Bipolar because I believed it, because I used the label to explain things that could have other explanations, other meanings. It was a belief that I thought kept me alive. But in the end, my story is that identifying with that word nearly killed me.