People Hard to Swallow

(Don’t) Fear the Feeding Tube

My feeding tube could make my life easier and better, but a visceral shame pulsed through me when it came to actually using it.

Before we figured out why I lost the ability to swallow solid food, Mom kept warning me about feeding tubes. If I didn’t start eating, she said, the doctors would have no choice. As a teen, she’d been in a car accident that left her intubated in a burn unit for months, so I believed her when she said, “You don’t want that.”

With every bite I forced down—and especially every bite I couldn’t force down—I imagined latex-gloved hands pushing a tube up my nostril, imagined gagging as it slimed down the back of my throat and further, past where I could track its progress by feel. Feeding tubes were scarier to me than anything else, largely because they were concrete, tactile in a way my other fears (of cancer, of surgery, of death) were not. Even after we discovered the cause of my swallowing issues and I switched to a liquid diet, feeding tubes seemed to present a threat. If smoothies and soups weren’t enough, I knew what would come next. Or I thought I did.

When I posted in a feminist Facebook group looking for smoothie recipes, a woman I’d gone to summer camp with as a child messaged me. She invited me to join a Facebook group for people with Muscular Dystrophy. She said the members would have plenty of suggestions about nutrition since many had similar swallowing issues. “And if it comes to it,” she said, “don’t fear the g-tube. It was one of the best things I’ve ever done for myself.”

I’d never heard of a g-tube before, but context suggested it must be a feeding tube. She confirmed it was and described hers as “like a belly button piercing.” A small incision is made through both the abdominal wall and the stomach wall. A silicone feeding tube is threaded through and held in place by a “balloon” that anchors the stomach against the abdomen. There are variations in the details according to the patient’s body and the doctor’s preferences, but essentially: A hole is made and an object (jewelry; a feeding tube) is placed in its new home.

My body flooded warm at her explanation, skin tingling so hard I thought the outer layer of me might shake itself loose. An adrenaline spike—an instinctive response to a sudden precipice, body prepped for either flight or fall, certain of neither, convinced of both.

*

Before gastrostomy tubes (g-tubes) were developed in the nineteenth century, nutritional enemas of broth, milk, or brandy were the go-to method when patients couldn’t nourish themselves orally. It was partly because we knew so little about how digestion works; while autopsies led to some understanding of the organs involved and the path from mouth to rectum, it was impossible to see what happened during the process of digestion. Did the stomach mechanically chew food, like a second set of teeth buried among our innards? Or did some slurry of juices dissolve what we ate before passing it off to the intestines?

These and other questions were finally answered in the 1820s and 1830s thanks to Alexis St. Martin, who, after being accidentally shot at close range, had a permanent hole (medically known as a fistula) that opened directly into his stomach. St. Martin’s doctor, William Beaumont, studied and experimented on St. Martin for over a decade. The fistula acted as a literal window into the main site of digestion, an area doctors had been unable to explore prior. And explore Beaumont did, often in painful and gruesome ways. In addition to simply watching St. Martin’s food break down in his stomach, Beaumont dangled hunks of meat on a string in the hole, sampled vials upon vials of stomach acid, slipped spoons or other objects into the opening, and even once licked the inside of St. Martin’s stomach to determine whether there was an acidic taste (there wasn’t, so long as no active digestion was happening). His findings revolutionized gastric medicine and paved the way for the future of gastrostomy.

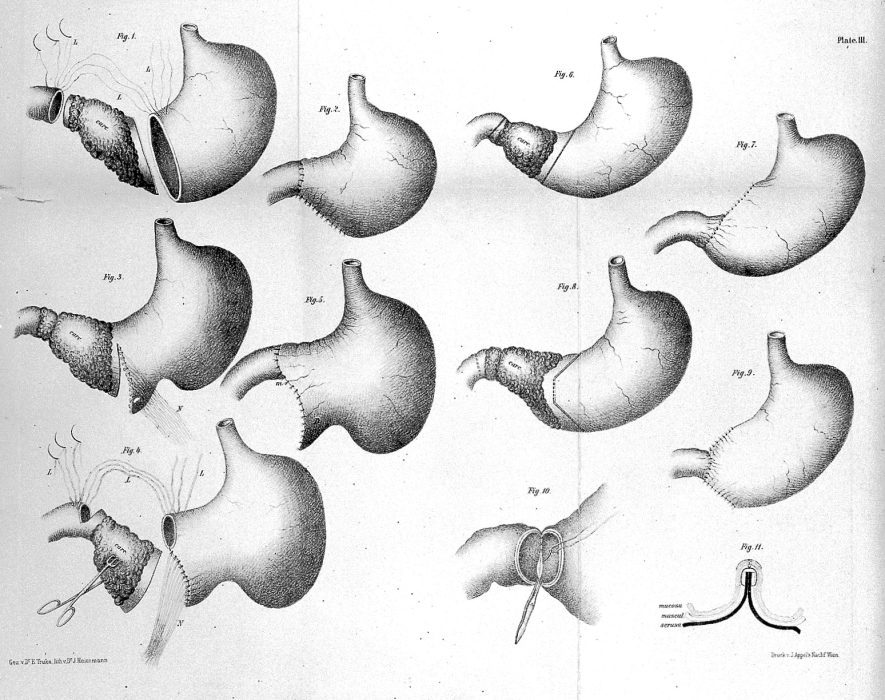

The earliest recorded surgical gastrostomy (the medical creation of an opening into the stomach) happened in 1849. Over the next several decades, doctors performed more surgeries, without much success. As Gayle Maynard discusses in her history of feeding tubes, most of those early patients died within hours. A few lasted days or a month. One little boy, the extreme exception, lived nearly twenty years by chewing his food before inserting it into his feeding tube. The real breakthrough came in 1894 with what is now known as the Stamm gastrostomy, named for its inventor. Unlike its predecessors, this procedure included the creation of an artificial sphincter around the newly inserted tube to prevent any stomach leakages. Apart from a few minor tweaks, the Stamm gastrostomy is still one of the most commonly used techniques today.

*

I couldn’t contain myself after my brief conversation with my former fellow camper. As soon as Mom got home from work that day, I gleefully, almost wonderingly, said, “You were wrong! About feeding tubes. You were wrong.”

A few months later I was wearing a hospital gown, all jewelry removed, lying uncomfortably in a hospital bed, ready for surgery. I was still drinking my smoothies, but not as easily. I didn’t need a g-tube yet, but both my doctor and my friend assured me it’s better to get one earlier rather than later. Anesthesia is dangerous for me, so I would be going under twilight sedation instead. I’d technically be awake throughout, but the drug would ensure I had no memory of being so. The anesthesiologist said its proper name was Propofol. Like a schoolkid excited to know an answer before his classmates, Dad said, “Oh, like what killed Michael Jackson!”

The woman smiled politely at the familiar response and assured me this would be nothing at all like Michael Jackson. She gave me small amounts in ten- and fifteen-minute increments. She and the surgeon wanted me unaware, but only to a point—too much sedation and my lungs could give out. (The earliest gastrostomies were performed under chloroform anesthesia, a popular method despite the high risks, including respiratory failure.)

“How do you feel now?” she asked after each incremental ratcheting.

“No different,” I said for a few rounds. Then I suddenly felt very different, and then I felt nothing.

My first, slurred words upon returning to my consciousness were spoken through a raw throat and a cold haze: “I’m so glad I didn’t die.” The people filling the operating room—at least ten, maybe fifteen—laughed. Probably because, though all surgery carries risk, my wide-eyed awe was disproportionate to the risk of this routine, outpatient procedure.

I wasn’t talking solely about the surgery.

In the worst moments of that summer, I’d had the fleeting thought that maybe things would be better—easier, certainly, if I died. I didn’t want to kill myself, not in any active way. I had no plan. I had hurt myself, yes: scratching my chest so hard I tore off a patch of skin that later became infected, biting my knuckles hard enough to leave indents for a few hours, pinching the back of my hand, clenching my fists until the muscles seized. These seemed like small things. A way to release the anger and fear that coursed through me like a new bloodstream circulating parallel to the original, emotional toxins building up and up and up with every heartbeat until my skin felt inadequate to contain the pressure. The small hurts opened small valves. I wasn’t suicidal. But maybe if my body simply decided to shut down on its own . . . that might be okay.

*

My body didn’t respond well to the Propofol. I got home from the hospital and spent the next eighteen hours nauseated, alternately breaking into cold sweats and hot to the point of feeling faint. Every thirty minutes or so I would grab the puke bucket (an old brown mixing bowl that’s never been used for cooking). Saliva would fill my mouth, stomach and diaphragm clenching in preparation—only for the sensation to pass without incident. The cycle continued until morning. Neither Dad nor I slept. (Mom was on a cruise she’d booked a year in advance with my sister.)

I think the stress and exhaustion of that night is why we didn’t solve the problem of transferring me out of my wheelchair until later. The sling I use to get in and out of my wheelchair has straps that slip under my thighs and crisscross in front of my stomach—right where my new fistula was. The pain of those straps digging in was unbearable. We did the only thing we could think of: Skip the crisscross when transferring, and skip transferring at all wherever possible. For five days and five nights, until we realized we could simply belt my knees together, I slept in my chair.

Wheelchairs aren’t made to be slept in. After five days, my body was in pure, constant pain. I hurt too much to brush my teeth. I hurt too much to even consider showering. I dreaded having to pee. I dreaded trying to sleep. Arm and leg and torso became meaningless descriptors, because my body was no longer a collection of parts hinged together by joint and sinew; my body was whole in its pain.

The one exception was my tube. The site itself was as my friend had said: sore, but not terribly so. And I was fascinated by my new appendage. It snaked out of me, fully sixteen inches visible. A nurse taught us to spin it once a day, “like when you get your ears pierced,” she said. She showed us how to check the contents of my stomach before every feeding. Thin, cloudy liquid pulled through the transparent tube and into the waiting syringe. After the acid was replaced (“Whatever you take out, you put back in”), we started pumping me full of formula. I felt it enter—all the way in my chest, like it had traveled against gravity, retracing the steps it should have taken from esophagus down. Not a painful sensation, just exceedingly strange.

When not in use, we curled the tube up and around, arcing under my breasts and across my ribcage, held safely against my skin until I needed it.

*

The first night I truly slept, ten days after surgery, I was in bed for fifteen hours. I woke once, around two o’clock, and couldn’t feel my body. I had lost sense of my boundaries; couldn’t define my physical form in the dark and warm. I didn’t want to, either—I didn’t want the pain to come flooding back. I wanted this respite to extend forever.

Maybe this no-feeling is what would have come on the operating table if my body had chosen not to cooperate with the anesthesia. I thought suddenly about the movie Secretary, which I had seen the year before. At the end of the film, Maggie Gyllenhaal’s character has spent days sitting in a desk chair, unmoving. She is exhausted, soiled, in pain; she’s trying to convince the man she loves that their (Dominant/submissive) relationship is good, healthy, loving, worth pursuing. He comes to get her, carries her gently from the desk to his home. He bathes her, massages her, soothes, and comforts her. She relaxes into his careful touch, her body in painful, blissful recovery.

Lying numb in my bed, that scene appeared in my mind and I willed myself back into my aching body. At first my fingers didn’t respond, like the signal had been misplaced, but when I found their edges I drummed them against the bed until sensation tiptoed along the rest of me. In slow stages, I felt the cradle of mattress beneath me, the support of a firm pillow, the tender softness of flannel sheets, the weight and warmth of a faux-down comforter. I hurt, and I knew the pleasure of pain temporarily relieved.

*

Even after recovery, I rarely used my feeding tube. For months I kept forcing down smoothie after smoothie, conceding to take one tube-fed meal per day. I said it was because I liked the smoothies (which I did) and because I could manage (which I couldn’t). Drinking them got invariably harder. I was exhausting myself in trying to keep myself alive: the exact problem surgery was supposed to solve.

“Why did you get the g-tube if you aren’t going to use it?” my doctor asked during the six-week post-op appointment. A reasonable question. One I felt an unreasonable anger at being asked, because questions expect answers, and I was unwilling to offer any.

After my research and conversations, I hadn’t feared getting the g-tube. But now that it was an irreversible part of my reality, I feared relying on it in any meaningful way. Whenever Mom spotted me struggling to get down my soup or smoothie of the day and asked if I’d rather—

“No,” I’d say before she could finish.

My feeding tube could make my life unbelievably easier and quantifiably better, but a visceral, inexplicable shame pulsed through me when it came to actually using the thing.

The daily ritual of “sucking out” (as we started calling the process of checking for issues with the tube) continued to fascinate me, though. Every day was different. The color, amount, even texture of the liquid we pulled from inside changed for no discernible reason. This was normal, we were assured, so I was free to be intrigued without worrying. The human body excretes plenty of various fluids and substances all the time, so maybe my delight was uncalled for. But snot, saliva, urine, feces, sweat are mundanities, not only in the daily nature of their presence, but in the fact that all humans experience them. Not many people can whip out their stomach’s contents on a whim. A strange party trick, to be sure, but one I was proud of, as if I’d gained some new and exciting talent. More than that, knowing what was inside felt like sharing a secret with myself. Seeing inside my gut, learning to recognize its patterns and moods, felt intimate in a way that was wholly unexpected but altogether a joy.

So why was I so reluctant to put anything in ? Why should there should be any difference between my wheelchair as an assistive device and my feeding tube as an assistive device? The sensation was weird, yes. If we went too fast, my stomach would slosh for ten minutes after we finished, like I had a mini-tide pool at my core. And I was more paranoid than was warranted that something was going to pop loose or pull free if we messed with it. But neither of those, together or separate, were reason enough for me to be so averse to putting this new tool to use.

Maybe it was resentment, then. I missed food. I would have traded a year of my life, Princess Bride- style, for a cheeseburger with cheddar topped with ketchup and mayonnaise. When my parents cooked sausage and potatoes, or pizza, or spaghetti, or chicken and rice, the desire for those once-familiar flavors, for the heat, for the texture drove me to swipe baby oil over my top lip to try to drown out at least some of the scent. Sautéed onions alone were enough to make me involuntarily growl, some animalistic instinct come alive. Formula-filled syringes couldn’t possibly compare. The shake of the small box in preparation of each feeding just reminded me of what I could no longer have.

If that resentment was part of why I resisted, though, I refused to voice it aloud. I wouldn’t play to the stereotype. I wouldn’t be a bitter cripple.

But wasn’t I one? I felt like one. Weren’t the juices I pulled from within myself bitter? An acid designed to corrode, to convert all manner of matter into fuel. Bitterness swirled sharp and newly familiar inside me.

But being bitter isn’t the same thing as grieving. And grief isn’t the same thing as denial. I was under no illusion about the ways my life had changed: I would never again have that cheeseburger. Never again face the challenge of a plate of barbecue with all the fixings. No more tuna melts or biscuits and gravy or simple turkey sandwiches. Spring would no longer mean boxes of Samoas and Do-Si-Dos. I was in denial, but not about the food—about the optics.

*

Whenever a parent murders their disabled child, the narrative is always the same: Those poor parents, under so much stress, having to care for someone who couldn’t care for themselves. When describing the murdered child, there’s usually the same litany of physical limitations. They couldn’t walk. They would have needed to be bathed, toileted, dressed for the rest of their life (had they been allowed to have one). They were on oxygen or would have needed to be eventually. They weren’t even able to eat on their own; they were forced to use a feeding tube. How horrible.

On average, one disabled person a week is murdered by a parent or caregiver. The articles that cover those once-a-week deaths as mercies are, for all intents and purposes, describing me. Hard not to let that get at you, even if you’re able to articulate the many fucked up angles of that particular argument. Even if you believe all those arguments are particularly fucked up.

Before, I could eat. Now, I couldn’t. Now, I needed a feeding tube.

Hard not to hear all those voices in all those articles covering all those murders over all those years echoing in your mind.

I wouldn’t tell my doctor why I refused to use my feeding tube because I was ashamed of the answer. I’m supposed to be a proud disabled woman, one who has built a career on exploring and dismantling ableism. I could barely admit to myself, let alone to anyone else, that I had this festering pool of the stuff inside me. I should have rooted it out by now. I shouldn’t be this stunted.

I didn’t tell my doctor the truth, didn’t tell him much of anything. But his question prompted me to ask the same and more of myself—and to re-contextualize my answers. My bitterness, for instance.

Maybe it wasn’t about the food or the admittedly significant change to my life, but was rather directed at those voices ringing so steady and so loud in my head, telling me that a feeding tube is anything other than a tool; telling me my death would be a mercy. Maybe my bitterness, like the stomach acid I was now on intimate terms with, was useful after all, converting the bullshit presented as truth into simply bullshit, into something worth fighting against wherever it might be found—including inside me. Matter into fuel. If feeding tubes and wheelchairs were tools, maybe bitterness and pain could be, too.