Catapult Extra Excerpts

A Conversation with PEN America Best Debut Short Story Author Samuel Clare Knights

“I wanted to write about the experience of my first language, about learning how to ask through hands before words.”

On August 22, Catapult will publish PEN America Best Debut Short Stories 2017 , the inaugural edition of an anthology celebrating outstanding new fiction writers published by literary magazines around the world. In the weeks leading up to publication, we’ll feature a Q&A with the contributors, whose stories were selected for the anthology by judges Marie-Helene Bertino, Kelly Link, and Nina McConigley, and awarded PEN’s Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. Submissions for the 2018 awards are open now.

*

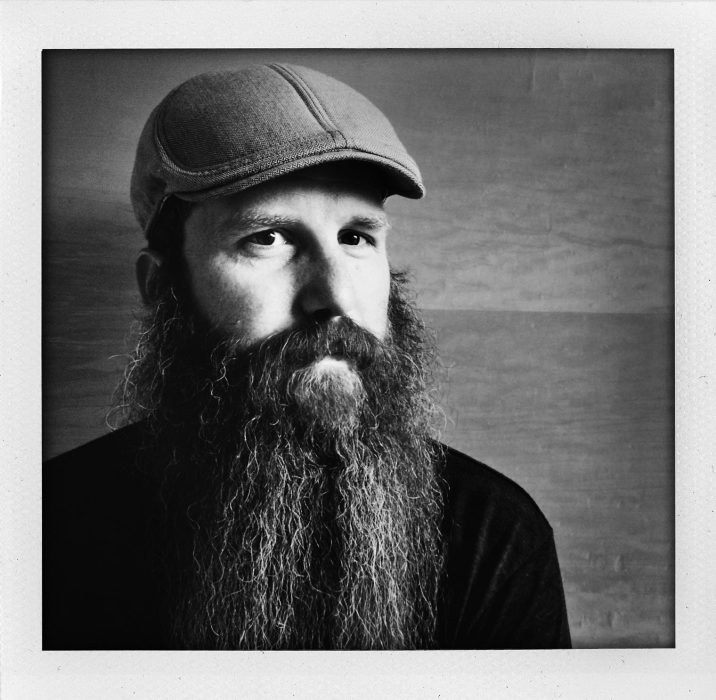

Samuel Clare Knights was born and raised in Saginaw, Michigan. He holds a PhD in creative writing and literature from the University of Denver and an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University. He lives in Colorado and listens to the Grateful Dead every day. “The Manual Alphabet,” a beautiful story told partially in sign language, is about a hearing boy born to deaf parents.

*

Catapult Books: Where did you find the idea for this story?

Samuel Clare Knights: Having been born to deaf parents, “The Manual Alphabet” is vastly nonfictional. And although it is my family story, it was an elusive process in terms of “finding” the way to tell. It was difficult to account and my expectations were unusually high before sitting down to flesh the memories out. But that’s one of the things I’ve learned about writing: that things will shape themselves on the page regardless of the intentions I privilege. For some reason it wasn’t until I allowed myself to write through an “I” that the conjuring of these moments started to constellate.

The story plays with form and imagery—literally, using images of hand signs. How did you decide to include the illustrations?

The images of the hand signs came to mind first. I kept seeing these glances and flickers and I wanted to write about the experience of my first language, about learning how to ask through hands before words. As for the actual illustrations used, I commissioned them from a friend of mine, Michelle Kondrich, as most of the manual alphabets available in books didn’t strike me. I asked her to illustrate an alphabet that looked drawn, that had the mark of a hand drawing a hand.

The story explores the loneliness of being bilingual, with one language used only at home, and the other used almost exclusively outside the home. Can you talk about why you chose to explore this from the perspective of a young child?

This is what it felt like growing up. Signing was the language of the house and didn’t seem to have much of a place outside the home. I recall our family always being stared at while signing in public spaces. The perspective of a young child was sort of natural: beginning at the beginning. But the story didn’t materialize in a line. Memories had to manifest. It wasn’t until I felt I had enough memories accounted for that I started to reckon the points and connect them with invisible lines.

Can you talk a little bit about the ending?

It was a way out. I feel a kinship with the ampersand, as I adore how “&” was once considered the twenty-seventh letter. So being this invisible ending to the alphabet evoked so much silence for me. I have read that the ampersand is a ligature (compound of e and t ), a mondegreen (mistaken pronunciation of “and per se—and”), and our symbol for connecting. As such, “&” resonated with me as a sign, as an open secret, as an alibi. “&” is a kind of ending to me.

How long did it take you to write the story?

This has been a slow draw and I’ve been patient. I’ve been thinking about this story and writing in small bursts over a much longer span, but the actual tick-tock occurred over the four years I pursued my doctorate at the University of Denver. My professors, my peers, and that space helped give way.

How has the Robert J. Dau prize affected you?

It has imparted a kind of private permission I didn’t know I needed. I know writing is not about rewards or recognition, but as an aspiring writer sometimes you need a hand to clasp your hand. I am grateful.

What are you working on now?

I’m still expanding this story. The Manual Alphabet is a book-length sequence yet to be published in full. Right now the manuscript is at about 150 pages. I see more pages coming. It functions the same way as this short story, but with more gaps, hands, longer breaths, and other ruptures.

How do you discover new writing?

I feel “new” can also be discovery of the forgotten. I will never lose how important Roethke was for me when I found him. And on some days he still feels new to me. As for my own process, I discover new writing below writing. I write by hand on blank sheets of paper and just turn it on like a faucet. I force myself to not lift the pencil until the page is full. After that I read it over and privilege words, phrases, or sentences and write them atop blank pieces of paper to let new writing descend.