Arts & Culture Rekindle

Living in Translation, or Why I Love Daffodils, an Unpopular Postcolonial Flower

For generations, Indians had to learn a poem about a flower most would rarely see.

In 1994, when I was ten years old, two significant events shook my life. Don’t take them too seriously, but here they are.

The first one took place at my father’s office. Built during the early years following India’s birth as a republic, it looked older than its age due to poor maintenance. Like any other government office, its interior walls were decorated with portraits and framed quotes from political leaders. One day, while visiting my father, I read such a quote on the wall that would forever shape my relationship with the English language: “There is nothing sadder than the practice that Independent India’s traffic signals are in English—M K Gandhi.”

The second event was terrifying. That month, my school announced a new diktat: No one would speak in a language other than English within the school premises. This was to instill the ability to speak in English—one of the perceived dividends of studying in an English-medium school, which only people with at least some middle-class money could afford .

These events caused a severe identity crisis. Before, I used to write stories about animals talking amongst each other like human beings—this was the product of reading Aesop’s Fables , in Assamese translation, a gift from my parents. In my English-medium school, I was required to read and write in English. At home, I mostly read Assamese books, encouraged by my parents. But I had written those stories where animals speak to each other in English. My upbringing and practice didn’t privilege one language over another—but now, pressured by the diktat and the guilt after reading the quote by Gandhi, I stopped writing.

I had no idea that a random quote and a diktat were capturing India’s complicated relationship with the English language and the ambivalent relationship Indian literary minds still have with Indian writers in English. I was suffering from a dilemma that every Indian writer suffered or was made to suffer by the literary pundits: Why are you writing in English? Is it because you want to pander to the West?

But it is literature. Things are more complicated than righteous outrage.

*

Unlike many of my other schoolmates, I didn’t speak English at home. My father grew up poor in a village where the only English words used were the ones that had percolated deep into the Indian languages and were no more considered English: telephone, inland letter, telegram, Colgate, kerosene (daily necessity, since we didn’t have power), etc. On the other hand, my mother grew up in poverty in a small town called Golaghat and studied in an Assamese-medium government school, but never spoke English except in phrases, only when necessary. A professor of Assamese literature, her quotes, framed or unframed, came from the vast repertoire of the literary body in which she earned a doctorate. My parents didn’t have access to English books and didn’t read English, unless required.

Unable to resolve the language dilemma, I decided to broach the matter at the dinner table, announcing that I would never write in English again. After a while, Ma suggested, “You don’t have to stop writing in English. You can also write in Assamese. You should write in a language that makes you feel happy.” I was surprised by these possibilities. I had little idea that my parents offered me one of the greatest lessons about languages. Language has power, but some languages have more power because of historical circumstances. This inequality also persists because we continue to give some languages more power and don’t nourish the languages we care about.

These parameters—of living in perennial translation, and accepting that not everything is accessible—were foundational to me as a writer. Reading and writing in two languages without feeling any shame, despite the surroundings that told me again and again that English is more valuable in India, allowed me to understand what I would read about ten years later as a student in Delhi University in Decolonising the Mind by Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The book would leave a lasting impact on me, vindicating the idea that all languages are equal. Thiong’o believes in a network of languages, instead of the hierarchies that colonialism introduced. In a detailed interview in Scroll.in , he explains, “I believe there is no big or small language . . . I can sum it up in one sentence: If you know all the languages of the world and you don’t know your mother tongue, that is enslavement, if you know your mother tongue and add all the languages of the world to it, that is empowerment.”

*

For most English writers, it is a famous English-language novel that encourages them to pursue writing: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart for Chimamanda Adichie, or Song of Solomon for Junot Diaz. Due to my parents’ upbringing, we had just a handful of English books at home, such as a tattered copy of Pride and Prejudice , Tales from Shakespeare by Charles Lamb and Mary Lamb, etc. My parents thought that their son’s English learning in school was enough. Perhaps that’s why one of the first novels to dismantle and remake my heart was by Assamese writer Indira Goswami: Dotal Hatir Uye Khowa Howdah (later translated from Assamese to English by the author as The Moth Eaten Howdah of the Tusker).

Set during pre-independence India in the district of Kamrup, Assam, the novel centers around the lives of three upper-caste women who are widows. Being upper-caste in India grants you enormous privilege based on heredity. But until a few decades ago, for an upper-caste widow, widowhood meant hell due to a mountain of restrictions, including fasting many times during the month on specific dates of the lunar calendar, and the most brutal thing: In a region that celebrates non-vegetarian cuisines, especially in Assamese and Bengali cultures, they were not allowed its pleasures. They had to shave their hair regularly because, without a husband, they don’t have the right to look pretty anymore. For the same reasons, they had to blacken their teeth permanently. At least in some parts of Assam, a widow’s white teeth were considered bad luck. These practices, not as stringent among lower caste families like us, percolated nevertheless based on the reach and popularity of Brahminical ideas. For instance, even though my grandfather passed away in the sixties, I saw my grandmother blackening her teeth until the early nineties .

Goswami, an upper-caste widow who was highly educated, escaped this life because she belonged to a prominent family. In Moth Eaten , the central story is that of Giribala. The story of this rebellious transgressive teenage widow—who is found eating meat, and who falls in love with a British manuscript curator, leading to tragic consequences—is unforgettable. Goswami’s life and writing would inspire and define a generation of women writers in India, and she would retire as Delhi University’s Professor Emeritus. Her widely popular novels were available in almost all of South Asia’s major languages before the English translations. She won all the major awards in India, including Jnanpith, India’s highest literary honor, and a European award called Principal Prince Claus Laureate for her social activism and writing, the only Indian citizen to have won this prize. When I was a high school student, the novel wasn’t an easy read. Even though the narration is in standard Assamese, which I find no hurdle to read, the dialogues in the novel are in the South Kamrup dialect, from the village of Amranga. Not everyone in the state would find it easy to understand the dialogues, but it added a gritty realism to the book and made it impossible to translate.

The tragic story of Giribala and her aunts shook me to the core, saddening me for weeks. But it is the kind of satisfactory sadness and addictive rage only a powerful novel could provide. A few years later, when I was a student of English literature at Delhi University, I found a copy of this novel’s English translation (by the author) in a bookshop not very far from Professor Goswami’s Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies. I was disappointed to find that the dialogues in the translation are in standard English. The prose retains the original flavor, but the experience of reading it in English is different. Both versions of the book are compelling, heartbreaking, and follow the forbidden love stories of three widows, but I felt as if I was reading an entirely new book in English. When I read the original Assamese novel, the sounds that ring in my mind are far more redolent, immediate, with whiplashes’ power and speed. In English, something is missing.

Reading the novel full of stunning imagery and extended metaphors during my high school years helped me refine my prose. In my American creative writing classroom, when I talk about lush prose, I always bring up three of my favorites: Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, and Indira Goswami—the queen of metaphors and similes. However, it was the voice of the omniscient narrator that would stay with me even longer, shaping what I expect from fiction. Goswami used a local dialect in the Assamese edition. Many Assamese readers wouldn’t understand it with ease. But she didn’t assume her reader was dumb. She refused to make it accessible for people who didn’t speak in the dialect. Reading the book required work from the reader. But her fiction is for those who are ready to do that work.

*

The First Promise: I discovered the title in a friend’s SLAM book and I bought the book hoping it would be a love story. But it was only after reading the 600-plus pages that I realized this wasn’t a love story, but a bildungsroman, wrapped in a family saga. There is a list of characters in the beginning: fifty-four. No MFA instructor, no publisher, would recommend this large cast, and a workshop in North America would demolish it.

By Bengali writer Ashapurna Debi, The First Promise is the gripping story of child-bride Satya in nineteenth-century rural Bengal. Born in an upper-caste Brahmin family in a remote village, Satya refuses to accept patriarchal social norms. The character Satya questions domestic violence: Who gave men the right to beat their wives? If the deity of knowledge is a woman, why would women become blind or a widow if they learn how to read and write; and how come this bolt from the blue doesn’t apply to men who are allowed to pursue an education? In dramatic situations, young innocent Satya’s questions rattle the household, the village, the society. When she secretly learns how to write, her mother cries a river fearing God’s wrath while her aunts rain hyperbolic reprimands. Satya is proud, has supreme self-respect, and would go to any length to maintain that even if the costs are too high. Debi maintains that Satya is one of the many women in the late nineteenth century who questioned patriarchy. Hence, “Satya is one of the many first promises.” This novel is suspenseful, dramatic, and attempts to record only one of those thousands of stories.

Debi is an astonishing writer. She never received a formal education. She read from an early age, taught herself to write, married at fifteen, would write 179 novels and 3000 stories in a career spanning seven decades, and win India’s highest literary award, Jnanpith. Her stories mostly featured women. Men remained in the periphery. In her fiction, these women are fully realized and commit all the good and terrible things that we, as human beings, are capable of. If you want to read complex, cruel, generous, kind, ravenous, manipulative, stupid, cunning, boring, seductive, domineering, scheming, helpless, or any other kind of women, read Ashapurna Debi. Almost two decades later, I would teach the English translation of this novel by Indira Chowdhury in my American classroom. While talking about Ashapurna Debi’s feminist anti-colonial resistance in that postcolonial literature class, I would want to talk about how beautifully, effortlessly, she writes. I have not finished reading all her novels. But when people in the US talk about the prolific output of Joyce Carol Oates, I smile.

In my own creative writing, if I am not able to take a story ahead, or create a character, I pick up one of Debi’s books to learn. But it is the voice of the narrator that I often think about. Reading The First Promise meant entering a village in rural Bengal in the late nineteenth century. There were numerous things I didn’t understand about Bengali culture, rules, and regulations associated with the widows. Like Goswami, Debi didn’t infantilize her reader by pausing to translate it for me. She knew attentive and engaged readers would get it. Precocious readers would walk an extra mile the way I sought information from my aunts or a neighbor from West Bengal. Perhaps this is also because Goswami and Debi didn’t write with the anxiety of being seen as Indian. Unlike the Indian writer in English, they were also not forced to accommodate a reader who didn’t live in India; or understand complex Indian realities. Also, Indian readers know that India is confusing. We don’t feel alienated if we don’t understand some cultural or historical specificities. These parameters—of living in perennial translation, and accepting that not everything is accessible—were foundational to me as a writer.

*

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s excellent novel The Namesake , when Ashoke meets Ashima for the first time with his parents in a matchmaking scene, the parents ask her to recite the poem “Daffodils” by Wordsworth. Ashima is nineteen, and before this, two other men had come to “see” her. “The first had been a widower with four children. The second, a newspaper cartoonist who knew her father, had been hit by a bus in Esplanade and lost his left arm” (13). The novel turns this humiliating practice of matchmaking—that should highlight the choicelessness of most Indian women of that era—into a tender, even romantic, moment. I will come back to this situation in a moment. Please bear with me. I must talk about daffodils first.

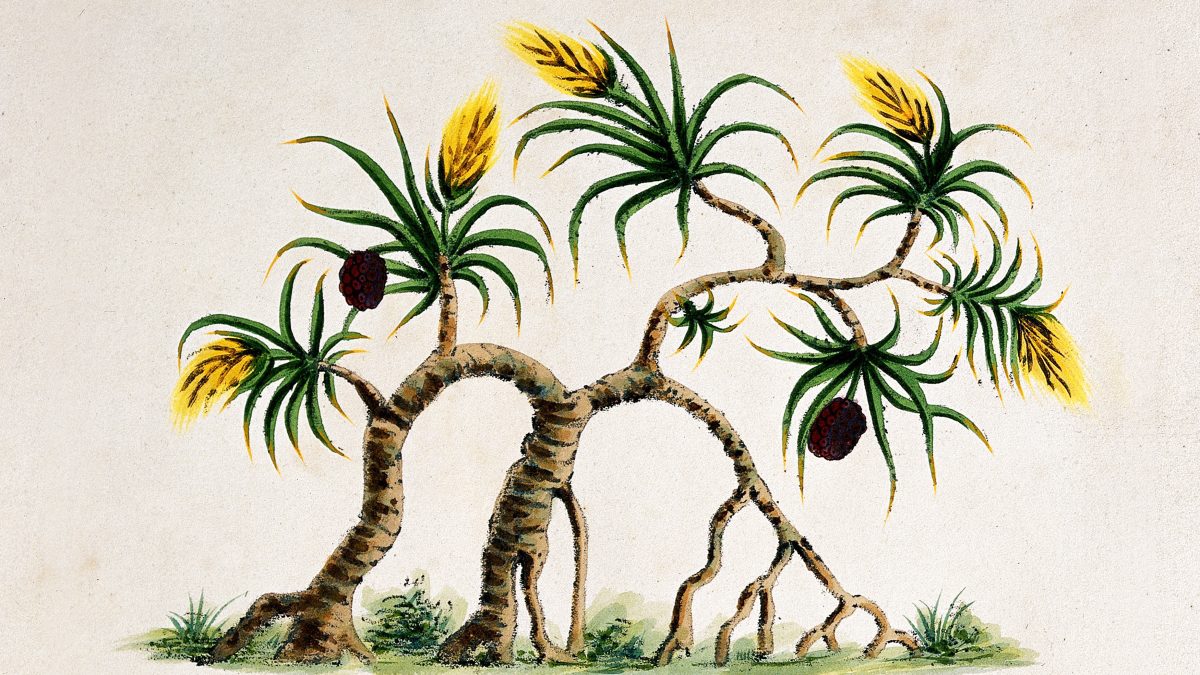

Daffodils, despite their sheer beauty, are perhaps one of the most disliked flowers among postcolonial writers. This is not the fault of poor William Wordsworth, who wrote a lovely poem—but of the colonial rulers. They imposed English learning in the colonies, forcing us to learn the language, hoping it would replace our regional languages. They were wrong. However, for generations, Indians had to learn a poem about a flower most would rarely see. If you have the questioning mind of a writer, it is hard to like the poem. If you are an anglophile, like Ashoke’s parents, you would love the flower without ever seeing or touching it.

How successful were the colonizers in popularizing daffodils—ahem, sorry—English in India? The colonial epistemological assault on the native languages has no doubt caused an enormous disparity. English continues to hold too much power and an iffy place in India. In postcolonial India, English is accessible easily only to those with power: caste and class (often gained hereditarily, like diabetes). Even today, learning English is aspirational, “cool.” “Spoken English” coaching centers grow like mushrooms on damp woods. That’s why instead of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, the 1913 Bengali Nobel laureate for literature, the parents in The Namesake ask Ashima to recite an English poem. What remains hidden under this scene’s surface is a culture of heterosexist patriarchal violence in matchmaking situations. But just as the family’s upper-caste Brahmin roots (they are the Gangulis, short for Gangopadhyay) mostly escape even the smart American reader, Ashima’s recitation is a happy, amusing moment for the novel’s foreign, primary, readers. This even excludes the Indian immigrant who may have a triggering response to this scene.

If you have the questioning mind of a writer, it is hard to like the poem. If you are an anglophile, you would love the flower without ever seeing or touching it. These primary readers don’t know that Ashima doesn’t have a choice. If Ashoke’s family asks her to sing, she would have to. If Ashoke’s family asks her to walk, to check her gait, she would have to. Her value is marked by her ability to be warm, sweet-spoken, walk well, sing well, recite well. They are looking for a certain kind of English-educated bride, and they want to know if she would be able to impress other future guests such as her husband’s colleagues, by uttering sentences in English if not a full poem. This unequal nature of Indian matchmaking is not explicitly made evident in the novel. In the same way, in this English-language novel, Ashoke’s immigration story that is enabled by access to English due to his upper-caste roots is also conspicuous by its absence. As “a provincial reader”—a phrase perhaps coined by Sumana Roy in her essay in The Los Angeles Review of Books —in India , excluded from these privileges, who didn’t go to an elite English school, grew up reading in Assamese, Bangla, Hindi, and less in English due to my class background, these inequalities were glaring to me.

These tensions might also characterize most Indian writers’ relationship with English, which is why only a few authors are widely read in India and abroad. These inequalities associated with English learning, hidden by the tradition of Indian Literature in English, are like that matchmaking scene treated tenderly in the novel. But underneath the sheen, it is a story that begins with epistemological violence; it is about the erasure of local languages and indigenous cultures, and self-hatred finding expression in the rejection of native culture and literature. When postcolonial scholars and writers become aware of this lifelong ignorance, they start performing postcolonial guilt by initiating the interaction of colonial texts with local history and culture. This process, despite its good subversive intentions, ironically re-centers the colonial knowledge system. In the neoliberal climate, this is a way of eliciting acceptance from the newly emerging bilingual, non-metropolitan, provincial, reader, writer, scholar who challenges their class and caste hegemony.

So far, the Indian English writer has been largely the product of enormous privilege (class, caste, gender). This started to change from the early ’90s due to a growing middle class and the economic liberalization in India from 1991. Anyone who had an elite English education before India’s liberalization in the early ’90s was usually in all probability rich/upper-caste. However, we must remember that attending an English-medium school even in the ’90s didn’t signal wealth. Even among English-medium schools, there are varying hierarchies. I went to the best school my parents could afford with their middle-class income, but applying to universities abroad after school was never a conversation. I never heard about an exam called the SAT until I moved to Delhi. On the other hand, most of my Delhi University classmates, who went to wealthy private schools, chose to study in India. They talked about things that sounded like Tamil—not even Greek—to us who were from humble middle-class backgrounds: statement of purpose, recommendation letters, IELTS or TOEFL, etc. I once had an English teacher who couldn’t speak English. She taught us in Hindi. We had to write the answers in the board exam in English.

The Indian English literary space remains a contested space because only ten percent of India’s population knows how to read and write English. At the same time, the rest of the population expresses itself in one of the twenty-two official languages. Like my first language, Assamese, these languages have strong sustained literary traditions dating back to a few hundred years, or even up to 2000. This is the literature that the bulk of India consumes; written, edited, and published outside the mediation of foreign publishing houses/gatekeepers. So I guess it should be clear why people in India get upset when an Indian writer gets a prestigious literary prize and is read widely across the world, especially the English-speaking world. Why should they have the right to represent us? People ask. They don’t understand us, study us, translate us, support us, dialogue with us, why do they get to represent Indian realities disproportionately and often in a skewed way? Due to white gatekeepers or people of color who are products of predominantly white knowledge systems, only a certain easily translatable truth is picked for publishing.

An old debate in Indian English writing, thousands of dissertations have been written discussing this topic. Many camps have formed and perished. Literary conferences have turned into warzones. But the reality sustains and rankles: The Indian English writer stands on a platform enabled by a violent, aggressive, contested world of exclusion. How do we work towards amending this? Should we have all our traffic signals in Indian languages? Should we stop writing in English? Should we popularize framed quotes and make everyone feel guilty with Gandhi’s words?

*

Perhaps the solution is hinted at in The Shadow Lines by Amitav Ghosh: a widely read, loved, taught, Indian English novel. Like many diasporic novels, even this novel deals with the west, immigration, border crossing, but it is the story that takes precedence. No one would pick up this book to learn what it means to live in India or get an Indian experience, but to be immersed in the vivid, quirky family; the engrossing, funny narrative voice. India is depicted with minute details here, but it doesn’t seek to explain Indian reality for anyone. The novel’s narrator also doesn’t nod to, or accommodate the imagined, global reader; nor does it simplify Indian realities but rather, by dealing with the partition of India as its major theme, questions the futility of borders or the idea of India itself. Here, Indian experience isn’t nostalgia in the form of a snack, enjoyed from the comforting assurance of New England, but a tactile, tangible experience that even brings death through political violence. Above all, the aesthetic parameters it sets out for itself seems to align with what Indian writers in Indian languages have unintentionally set out for us who write about India in English. The narrator of this novel is not interested in an exotic, metaphorical, nostalgic India, but one that is varied and eclectic that he isn’t trying to explain to the non-Indian reader. It’s what Indira Goswami, Ashapurna Debi, or Sunil Ganguly didn’t set out to do as well.

While releasing the book’s Bengali edition, the great writer Sunil Ganguly quipped: This is a Bengali novel , just written in English. Reading that in an Indian magazine was a groundbreaking moment for me. I had realized why I went back over the years to Ghosh’s novel repeatedly to find inspiration. The first-person narrator was someone I could so easily connect with, find similar people even in my neighborhood, even though the family depicted in the novel was richer, more cosmopolitan than people I knew. It was because, like Goswami and Debi, Ghosh’s narrator was always speaking to me rather than translating the experience of an outsider audience. If I didn’t understand something, the narrator assumed I would find out without pausing to explain that and insult my intelligence.

This wasn’t the case with numerous other wonderful Indian English novels that I read and felt disconnected from, published through the mediation of foreign presses. There are long passages in The Namesake, for instance, describing peculiar Bengali customs. These include why Bengalis have one name to use at home, another formal; and how to make a common snack called jhalmuri. I know how to make that snack, who are you explaining it for, I found myself asking while reading the moving, excellent novel; or the profoundly moving stories from The Interpreter of Maladies , a book I received as a prize during my undergrad after participating in a competition in Delhi University’s Indraprastha College for Women. Fortuitous that it was an American writer who would provide me with answers to these questions, who wrote in a sovereign language by refusing to be “consumed” or “concerned” by the white gaze : “It has nothing to do with who reads the book—everyone, I hope, of any race, any gender, any country,” Toni Morrison says. “The problem of being free to write the way you wish to without this other racialized gaze is a serious one for an African American writer.”

What kind of gaze haunts the Indian English writer? White gaze? The colonial gaze? Daffodil gaze? The Global Reader Gaze? Gandhi’s moralistic gaze that wants traffic signals to be in Indian languages? I am not sure. But since my Delhi University days, after reading Thiong’o’s radical text, I wonder: Can I write a kind of fiction that erases this gaze? Can I write an English language novel that is essentially Assamese in its posture, true to my tribal roots, in terms of the language I would employ just as Native American writers such as Louise Erdrich or LeAnne Howe do? How liberating would it be to write fiction and poetry without being forced to accommodate the reader that Indian writers have so far done in English? The standards set by Goswami, Debi, Ghosh, and Morrison enabled me to ask these questions as I write and search for a sovereign language that is free of whatever gaze Indian English Writing suffers from. Reading regularly not only in Assamese but also in Bengali, English, and Hindi meant that here’s a certain aesthetic standard I could borrow from. Commenting on the language of African writers such as Chinua Achebe, Morrison says, “ . . . there was a language, there was a posture, there were the parameters. I could step in now.”

But the most important benefit of my reading habit has been that I love daffodils; unlike other postcolonial minds, I don’t bristle with its mention . The first time I came across that poem, I asked my father. Busy with housework, my father said, “We have better flowers,” and told me about a flower called keteki with an aroma so strong and magnetic that snakes from far come to wrap themselves around it, unable to resist its incredible powdery smell that travels for miles at night—and that’s why the Assamese people don’t plant the flowers near the house. He fished out a small book that contained a poem called “Keteki” by Raghunath Choudhary and said , “Keteki is a singing bird in Assam. Go read this poem about it.” Whenever someone mentions daffodils, I don’t remember the terror of having to memorize that poem. I recall that incident of tenderness with my father—a moment of unintentional postcolonial resistance.

Perhaps that is the reason I write Assamese books in two languages—English and Assamese—and I feel slightly unsure when someone brands me, with the slightly flattening term, Indian English Writer. Goswami and Debi didn’t have to write with the burden of being Indian enough. These questions were incomprehensible for them. They wrote sans the pressures of proving their Indian-ness in front of an imagined reader.

Whenever someone mentions daffodils, I recall that incident of tenderness with my father—a moment of unintentional postcolonial resistance. In 2017, three years after my father retired after working in that government office for forty years, I went to deliver a letter to one of his colleagues. We didn’t live in the city anymore and I had just accepted a job in Georgia, shocking everyone because I was already in a job I liked. I was leaving India in two weeks.

To beat the winter, I was wearing a thin black cotton jacket. It was Calvin Klein—in fact, my first foray in a slightly expensive brand, bought with my first salary after a lifetime of wearing cheap local jeans. My second cousin was driving. As we drove through the campus towards the office on the hilltop, a flood of memories of living on this campus returned. After delivering the letter to the person concerned, I walked towards my father’s old room. Another colleague of his was sitting in that room.

I asked, “Where is that framed quote of Gandhi? Those large portraits?”

He burst out laughing. “Several years ago, we took them off. They will get new pictures.”

I was stunned. “Why this massive new decor change?”

“No, all those quotes were incorrect. Someone who was briefly in charge said that Gandhi never said that, Nehru never said that, and we checked and found that it was true. So we decided no more quotes, but only new portraits of the dead leaders.”

I was almost about to scream.

My heart was in my mouth, and there was only one thing that came to my mind: My entire life is a lie .