People I Survived

Checking for Holes in the Multiverse

I pick out the universe where a bullet never fractured my skull bone.

I’m sure my mother is relieved I’m not haunting her while she sulks around all grief-stricken. Whenever she gets really stressed out, a cold sore forms right below her nostril in the middle of her Cupid’s bow. I noticed it yesterday but didn’t say anything. I am the cause of all her stress lately. She is in the back row of the Chrysler, croaking nonsense baby talk to my sister’s infant daughter. My mom’s got puffy eyes and the baby is contorting all weird. I can tell little sleep was had last night between the two of them.

She’s singing the melody of “Ba Ba Black Sheep” but with “Doo’s” in exchange for the traditional folk lyrics. My boyish sense of humor sends a signal for me to smile at every coupling of her curiously-selected syllable. It’s going on too long now so the fun stops for me. I’m so out of it I can’t tell her to quit. She should know better. The appointment that would clear me to drive is still two weeks away, which means I’m in the passenger seat due to my long legs. My sister is behind the wheel with her cell phone’s GPS open in her lap.

The light and sound sensitivity, I was told, is a common symptom. I pull a beanie over my head and look through the stitching, the pores. Focusing in on one hole helps with the overstimulation. Each hole is a little different. I pretend it’s like the sponge theory of the multiverse. In this world, they only have hybrid cars with license plates reading CVK-788. In that one, only anti-abortion billboards.

Before we left, I mentioned slipping into the fertility clinic floor of the hospital to donate sperm and to make a quick buck. My mom didn’t take to that. She said a traumatic brain injury is not to be spoken of lightly. She is worried about residuals—namely, poor sleep and seizures. I was worried about residuals too, but now I’m more worried about what I’ll miss in life: theme parks; holding my breath underwater; a chance to date Emilia Clarke. I’m worried the injury took a few years off my life, too, that now I’m going to die sooner than originally planned.

We get off at our exit; the ride was quicker than expected. I peer out into a universe of my choosing from within my knit hat. A light beam glares through. I’m looking for a version of myself who isn’t getting nineteen staples removed from his head today.

*

Back in time: four hours after the craniotomy operation. I have brand new metal plates fusing to my skull, and a gauze wrap around my face that makes me look like someone’s sickly grandmother with raccoon eyes. My hair is shaved off. Never in my life has it been this short. I was born into this world with a mop top and have only trimmed it since. The surgeon told me before anesthesia he felt bad for having to cut it all off. He said I had really great hair. I told him no biggie. I’ll probably look more professional when I get back on the horse looking for a job after graduation. He said it should grow back by then.

I snap out of anesthesia. The hospital room is painted an unsettling burnt-copper color and I have an IV in each arm. My eyes open slowly as if by a crank-and-pulley system. Word must have gotten out because there are flowers and baskets littered about the space containing Easter chocolate and Fandango gift cards. My mom is holding a brown package.

“Hi buddy,” she says. “Something came in the mail for you.”

I languidly shake my head up and down. My throat is too coarse for words from the plastic breathing tube during surgery. She opens the package and shows me the contents. It’s a bunch of socks. Strangers donated and sent me a boxful of socks. My mom holds up each pair individually like she is trying to auction them off or model them for an infomercial.

“Superman,” she says. “That’s fitting for you isn’t it? Here’s one that’s argyle.” She lays them down neatly on the end table next to my bed. “Paisley. And then we have stripes.” She holds up a pair with little handlebar mustaches printed all over. I lose it and turn my head over to cry. I don’t want her to see.

The maneuver hurts more than expected. She grabs my hand and I wipe the tear away with my shoulder. I think about when I would have night terrors. When she would always come by the third time I yelled “Mom,” then scuttle me down the hallway towards her bedroom to sleep soundly until daybreak. I don’t want her sympathy. I’m selfish.

It is really bright. I pull the covers over my head and peer through the porous cream fabric. I’m looking for a version of myself who doesn’t rely on painkillers or need a chair to shower today.

*

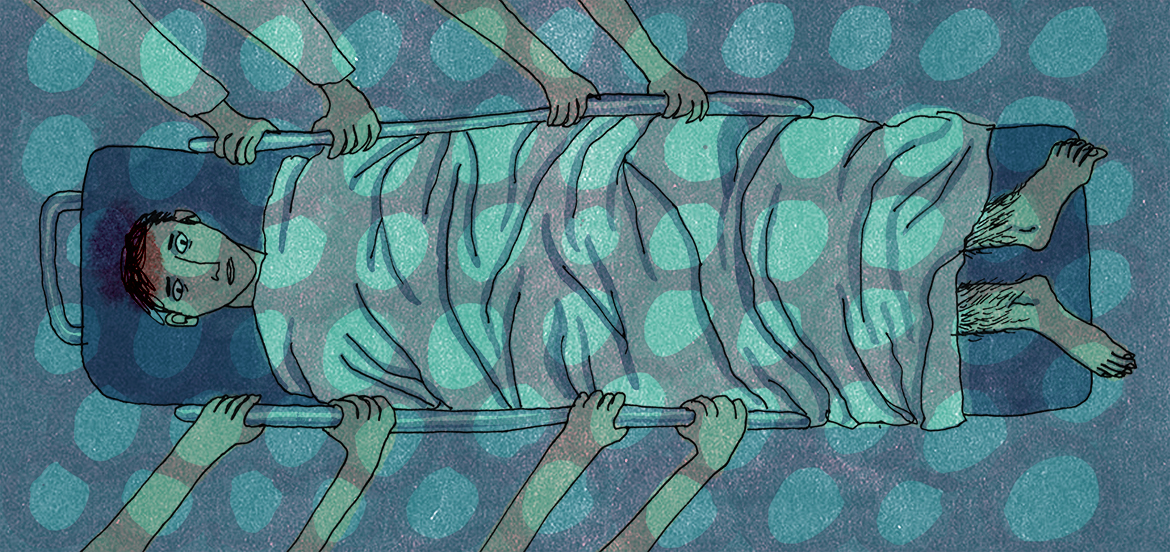

I am rushed to the ER on a stretcher. My clothes are sheared off by a horde of people wearing scrubs and masks. They work me over quick. A fraction of my boxers are left to cover me, a contemporary loincloth somebody might see at a prehistoric-themed male strip club. The rest is placed in a bag labeled “flannel undergarment” by the police as evidence. I am embarrassed by my pubic hair. I didn’t know I was going to have an audience tonight. It is grown out a little long past my personal preference.

“Regions Hospital. Yes. Yes. No. Just get here,” a nurse says over the phone. “Your mother is on her way. I’m going to ask you some questions, okay?”

I nod.

“What’s your birthday?”

“Twelve. Twenty-one. Ninety-four.”

“Full name?”

“Paul Jacob Rousseau.”

“Who’s the current President?”

“Donald Trump, regretfully.”

“You’re sure he only fired one shot?”

“Yes.”

“I’m going to check your vitals.” She takes a miniature flashlight, a ballpoint pen in disguise, and flashes it in each pupil. She says I have good blood pressure and I think this is the reward I get for eating healthy and never smoking cigarettes.

I feel something pouring onto my forehead like the cracked-egg trick kids show off in grade school. With two fingers I check to see what I already know. I’m still bleeding.

Someone grabs the back of my gurney and I’m carted off for a CT scan. I insist that I can hoist myself over to the machine without anyone carrying me. They say they wish I were every patient, but not really, given the circumstance.

“I’m going to give you some iodine through your IV,” a male nurse says. “Your face will feel flushed with warmth and you’ll get the sensation to urinate, but I promise you won’t.”

“Okay,” I say.

He makes his way to a separate examination room. I feel like I’m in a slumber pod from the future when the instrument begins to hum in intervals, and a crescent-shaped part zips along above me. It executes a few passes over my head and I get the flush sensation in my face and an unexpected surge of discomfort at the injection site. The first thing that comes to mind when I try and think about something else is whale watching. After a couple minutes, the nurse comes back out to find that I did in fact piss myself.

He recruits some people to clean up the floor and leans over my prone body.

“I looked at your CT pictures. You are one lucky dude. Has anyone ever told you before that you were hard-headed?”

“Maybe.”

I’m wheeled back into the previous room and my mom is there waiting for me. Her eyeliner is smudged, cold sore already forming. I prop my hand up as an attempt to greet her.

“Hey.”

“Oh my God,” she says. She hugs me. “Are you okay?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “I guess I’m hard-headed.”

I squeeze my eyes shut, coming to terms with what happened. I’m no longer in shock. The inside of my lids look like bright orange petri dishes laced with pulsating amoebae. I pretend each formless shape is its own universe, and I pick out the one where a bullet never fractured my skull bone today.

*

I am with my roommate in our apartment. We are the only ones home. On the couch, side by side, laptops on laps. Television on for white noise.

“Want to grab a beer tonight somewhere?” he asks.

“Groveland after ten has got really cheap drinks on happy hour,” I say.

“That could be fun. Wings sound good too. I’m trying to decide if getting a little buzzed would be considered a warm-up, or actually hurt my performance tomorrow,” he says. Tomorrow he is supposed to drink an entire box of wine and then pedal around on a bike in a race.

“If it’s beer tonight, I don’t think it would impair your efforts,” I say.

“I kinda want to get buzzed up a lot today though,” he says.

“I don’t see why not,” I say.

“All right,” he says. “I’m going to watch Netflix in bed and maybe take a nap until then.”

“Have fun,” I say. He exits behind me. I stay in the living room, which is the centerpiece of our apartment, and the divide to each of our personal spaces. I’m working on a research paper. I get up to grab a book and something comes at me through the wall.

I feel blindsided, tackled into a pool of cough syrup. My ears buzz as if someone hit the monkey bars with a tree branch in my brain. My sight is a television color-quality test; I lift up my forearm and sand is pouring through it like an hourglass. I stand up to a head rush like when elderly people have low blood pressure. I trip on my own silly putty feet and leave several red handprints on many surfaces. The trail is random and confused. I’m fighting it. There is no pain yet.

I tell my legs to get up and walk but they stumble. I misstep and evaluate the depth of the floor all wrong. I fall over. I suspect a natural disaster or nuclear warfare. That’s how I ended up tossed into a couple wooden dining room chairs. An earthquake in Minnesota. The fire alarm starts going off.

My face is heavy, as though attached to one thousand fishhooks towing five hundred bags of sand. I park my body by the bathroom sink, using my palms as kickstands. I hesitate to see myself in the bathroom mirror.

I look for the end. I look for a hole in the middle of my forehead, or through an eye. A bullet could be wedged in there somewhere, killing me by the second. I part my already clumping hair to each side. My bangs now look like a drawn curtain; below my widow’s peak is a stage in a theatre. Nothing. Just skin. No thimble-sized intruder.

I check for the source of bleeding by poking around the top of my skull. I find an indent the depth of a peppermint candy. I see the round that struck me on the carpet. There is no exit wound so it must have bounced off my head. I move in close to my reflection and tilt my head like a holographic trading card to spot the bullet. I only see pink, red, and white. Nothing glimmers, or refracts. I look back towards the main room. The drywall above the couch is pretty messed up.

My roommate comes rushing out of his doorway with one hand over his mouth, the other holding a pistol.

“Shit! Shit shit shit fuck. I didn’t know it was loaded!”

He lays me down in bed with a pillow under my neck to reduce any swelling. He grabs a first-aid kit from his room. He bought it to go on solo hikes in California.

“You must really fucking hate me right now,” he says.

“No,” I say.

“There is no way, dude. You must really fucking hate me right now,” he says.

“No,” I say.

While he puts pressure on the gash with gauze, I look up at the popcorn ceiling. I had a popcorn ceiling in my first house and whenever my mom would put me in timeout, I’d look for faces in it. I find a face that resembles me a little and I imagine him graduating with honors in two months, like I would have. I imagine him finding a decent-paying job after college to chip away at student loans, and potentially moving out of his parent’s house. I imagine he is not as brave as me.