People I Survived

The Moment Your Life Crashes and Burns: On Divorce, Injury, and Questions Without Answers

It’s been more than four years since my husband announced he was in love with my friend and no longer wanted to be married to me.

The morning I got hit by a car was unseasonably warm by Boston standards. It was a Monday in late September and I was on my way to work. I paused at the corner of a side street, where a car was stopped at a stop sign, and then kept walking, crossing in front of the car. The driver didn’t see me, though, despite my bright yellow skirt, as he made his turn onto the one-way street. Though the car wasn’t going fast, the impact was enough to break my ankle in several places.

By the time I was able to walk on my own again, it was January, the day after a weather phenomenon newscasters coined a “bomb cyclone,” which left more than a foot of snow, frigid temperatures, and extensive flooding in its wake. In the four months between the accident and those first independent steps, I spent most of my time in my apartment, vacillating between feeling that life was passing me by and that time had stopped. My convalescence afforded me time to think. I found myself asking the kinds of questions that don’t have real answers, like “why me?” and “how did this happen?” and, most commonly, “what if?”

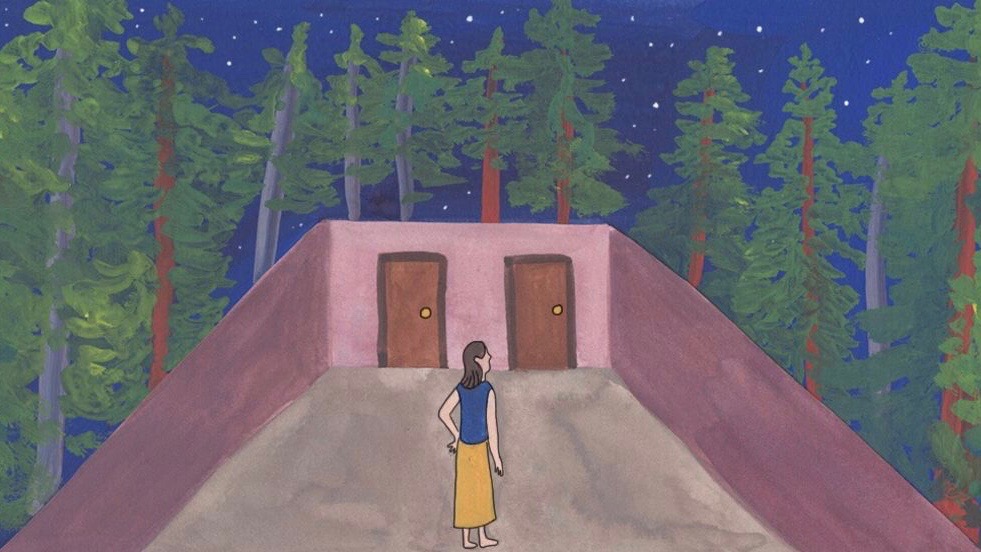

It has long been my instinct to seek alternatives, to wonder whether there were other paths I could have taken, decisions I could have made to avoid misfortune. My brain likes to imagine a scenario in which I have complete control, operating under the illusion that I have the power to affect my destiny rather than accepting the reality that sometimes bad things happen for no reason at all.

The 1998 movie Sliding Doors is a near-perfect exploration of this idea of parallel destinies. In it, Helen, a London PR executive played by Gwyneth Paltrow, loses her job (or “gets sacked” in the British parlance of the film) and rushes to catch the Tube. In one scenario, she manages to squeak inside the sliding doors, arriving home to find her failed novelist boyfriend in bed with an ex. In the other scenario, she narrowly misses the train, sustains a head injury in an attempted mugging, and arrives home after her boyfriend’s mistress has left, effectively missing the opportunity to walk out on him and start over, as the Helen of the first scenario does.

Sliding Doors shows a world in which our existence pivots precariously on the fulcrum of one moment. This is an especially seductive idea for those of us who are unhappy with our present situation. It gives us license to travel back in time, to try and pinpoint the moment our lives crashed and burned, when everything could have been different from the way it eventually turned out.

*

Until the day I got hit by a car, I’d never broken a bone, sprained a muscle, or been admitted to the hospital. Caution was my religion. When my doctor said my injury was “nasty,” the kind that excited doctors, I felt, briefly, special. It was like when I was told in fourth grade that I needed to wear glasses—both in the shine of novelty and how quickly the shine wore off.

One of the bones I’d broken, the talus, is one of the most difficult bones in the body to break due to its shape and location, hinging together the foot and ankle. In fact, talus fractures were relatively unknown until World War I, when cases were diagnosed in parachutists and other members of the Royal Air Force involved in plane crashes. Now, the talus accounts for approximately .1% of all fractures. I was basically a medical marvel. Of course, this didn’t help dull the pain radiating from my ankle, or quell the likelihood that I would develop early onset arthritis as a result of my injury. It also didn’t help the emotional strain and restlessness of finding myself under house arrest, though I’d done nothing wrong.

The two flights of concrete steps leading to my front door became my Everest, effectively trapping me indoors because I couldn’t go up and down them on one leg. I got a scooter and wheeled from my bedroom to the kitchen to the living room and back again. I was incredibly lucky to be able to work from home, using video software to call into meetings. Sometimes, on weekends, my family drove in from Rhode Island and took me grocery shopping, holding my crutches while I shuffled down the steps on my butt. My friends visited, bringing me wine and baked goods and gossip from the outside world. I learned how to live a limited version of my life, one in which I didn’t meet new people or encounter chance or feel the sun on my skin.

And throughout this time, there were the questions, repeating their syncopated dance through my brain every day. What if I’d gotten out of bed that morning when my alarm went off instead of scrolling through Twitter, a bad habit I’ve been trying to break for years, and left my house five, ten, fifteen minutes earlier? What if I’d been walking on the other side of the street, as I normally did? What had compelled me, that morning, to walk down the opposite sidewalk? What if I’d stopped and waited for the car that hit me to turn, despite the stop sign, despite knowing that as a pedestrian I had the right of way? What if the driver had looked both ways before making his turn? What if I’d fallen a different way and hit my head? What if I hadn’t had the luxury of being able to work from home? What if the driver hadn’t stopped, and instead sped away, leaving me responsible for the onslaught of medical bills and other expenses?

During the twelve and a half weeks of my house arrest, I also wondered about all that I was missing. In my “real life,” back when I was able to leave the house on my own, I was enjoying a busy social life, seeing friends and going to cultural events several times a week: parties, art exhibits, book readings, new restaurants, protests and rallies, drinks with friends, community meetings, holiday markets—events that once seemed like social obligations were now all swirling with the possibility and promise that comes with being forbidden, out of reach. I felt like a recluse, like an old woman, slow and frail and forgotten.

In addition to my injuries, I’d also picked up some kind of virus, leaving me with a cough that hollowed me out for months. I eventually visited the ER again six weeks after the accident, convinced I had pneumonia (I didn’t). Three weeks after the accident, my company underwent a reorganization and I was laid off, my position eliminated. My manager read from a script over the phone as I cried, unable to conceive of how I was going to manage all of the bills without health insurance, how I was going to get a new job when I couldn’t even leave my house.

Overwhelmed by my reality, sick and trapped and jobless, I constructed an alternate reality for myself, one in which I hadn’t been hit by a car, and had traveled to San Francisco on the business trip I was scheduled to take the day after the accident. In this timeline, I’d also taken the solo vacation I’d planned to Puerto Rico. In this timeline, I’d also gone on the date I had scheduled the night of the accident, and I’d actually liked the man. We’d go apple picking, see Lady Bird and Wonder Woman, and check out a new fried chicken restaurant. All in all, it was a pretty good timeline.

But perhaps worse than my fear that I was missing out on all of the things that were supposed to be happening to me was the nagging voice in my head that wondered whether, perhaps, I wasn’t missing much of anything at all. What if I hadn’t been hit by a car and my life had just continued along as it had been for the last four years since I’d moved back to Boston from New York City: a series of days in which I woke up, went to work, maybe got drinks with a friend, maybe went home to watch Netflix, went to sleep, and did it all over again? Winter was descending and I found myself settling into the comfort of being indoors, sheltered from the elements. Being confined to my house meant there were no chance encounters or visits to new places; however, it also meant I was protected from the disappointment of having the same underwhelming dates, of feeling trapped in my own life though I was free to go wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted.

*

It’s been more than four years since my husband announced out of nowhere he was in love with my friend and no longer wanted to be married to me. Yet the parallel timeline I think of the most, even as I explored various timelines tied to my car accident, is the one in which we are still married and he still loves me.

Now that I’ve been hit by a car, I can say the shock of that weekday December morning, sitting in our living room listening as he told me our marriage was over, was similar to the feeling of my body colliding with 4,000 pounds of steel in motion. He’d given no indication that he was unhappy prior to that conversation, never gave me a reason why he loved her more than he loved me. When he’d routinely told me that I was “perfect for him,” he’d decided after just a year of marriage that I was no longer good enough. Not good enough to stay faithful, not good enough to follow through with the eloquent vows he’d intoned at our wedding, not good enough to treat me like more than a stranger before he walked away forever, never turning back.

Perhaps spurred by that lack of closure, I’ve spent a lot of time in the ensuing years doing the same cruel mental geometry that followed my accident—what if I’d been more fun? What if I’d been a better cook? What if I’d been smarter, more well-read, prettier, skinnier, more adventurous in bed? What if I didn’t have punishing anxiety? What if I’d never met the friend he left me for? What if I hadn’t introduced her to my husband? What if I hadn’t gone out of town that spring weekend they’d first spent time together alone? What if we hadn’t lived in the crucible of New York City? What if we were still married? Would we have kids? What would they be like? Where would we live? What if I’d never dated my husband at all, and instead remained friends and experienced whatever life awaited me had I stayed in Boston? What if he and I had never met at all?

One of the questions that plague me most, though, is this: What if I could go back in time, back to the night we first confessed our feelings to each other, and change it, so that the following years, our relationship, our marriage, our divorce, had never happened? Would I do it?

*

The driver was well-dressed, about my age, his dark hair slicked back like bankers in ’80s movies. When he finally stopped the car, he was panicked, repeating “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry,” and “I didn’t see you,” over and over again. I fought the impulse to tell him it was okay, to comfort him though I was the one sitting on the curb, pavement embedded in my skin, crying tears of shock and pain. Instead, I told him, “I know.” Hitting a pedestrian has always been one of my greatest fears as a driver, so I empathized with him. But my ankle was also swelling to the size of a softball and I couldn’t stand up and why hadn’t he looked? It was Monday rush hour on a busy street that led directly to a subway station.

His “I didn’t see you” felt like an indictment, the very thing I fought against every day. The feeling of insignificance and invisibility had plagued me all my life, but most especially in the years since my husband had fashioned himself into a stranger, erasing photos of us from social media, never speaking to me again.

When healing a broken bone, it’s important to keep it protected, to keep it from harm’s way. This involves unlearning the ways you’ve used your body all your life. Where my leg had been supporting my weight for thirty-five years, now it was my turn to support my leg, to carry the weight on my own, to untwin it from my other leg. In many ways, it felt similar to learning how to be alone after being part of a couple for so long, to that process of carrying all of the weight myself.

*

Helen’s dual experiences in Sliding Doors are never quite explained; however, in both timelines, she eventually discovers her boyfriend’s infidelity, loses a baby, leaves him, and meets the man the movie leads you to believe is her soulmate. In essence: What will be, will be. The inevitable will happen, no matter what path you take to get there.

My husband and my friend moved in together to an apartment in the same neighborhood we’d lived in, weeks after I left the city. They got married a year later and moved across the country, taking the dog he and I had adopted together with them. They now have a son. I wonder if any of their new friends know how they met, that he was married before. I wonder if his son will ever find out. It is as though my existence is nothing more than a mistake, some fuck-up he made before he found his real life.

I wonder at this as I examine my current life—nearly six months after the accident, I can walk again, but pain hovers around the edges of my hours. I can’t run or go down stairs without holding on to the railing. I go to physical therapy twice a week. My right foot is still so swollen that some of my shoes don’t fit. It’s an adjustment from my pre-accident life, but it’s essentially the same as my life was before I moved to New York to be with the man I would eventually marry—I’m in Boston, working at the same company (where, luckily, I was able to get a new position after I was laid off), still single, still living with roommates. It is as though my marriage and life in New York was the alternate timeline, a brief interlude in what my real life was meant to be all along.

I think about what this past life has brought to my current life, beyond the longing for the kind of happiness I knew then and fear will never have again, an ache that is all pervasive but reaches its boiling point each year in the early weeks of December. Maybe there was no lesson in it at all, beyond understanding heartbreak. Or maybe I have those memories to show me there is no one destiny for anyone, no ready-made happy ending in store. Because no matter how many times I ask myself “what if?,” there is no answer. Life is complicated and messy, and it can change at any second—and that offers its own kind of hope.