Arts & Culture Rekindle

In Pursuit of Prodigy: The Last Samurai and Me

“Books are the cause of so many bad ideas.”

I wanted to be a prodigy, so when I was fifteen—despite knowing I was already too late—I decided to teach myself ancient Greek. I got Kaegi’s Greek Grammar and the Liddell & Scott dictionary, as well as a copy of Plato’s Ἀπολογία Σωκράτους, or the Apology of Socrates , because it was the shortest work of Greek literature I could find and I wasn’t trying to bite off more than I could chew. My expectations were conservative: to translate the Odyssey by my senior year of college. I was a sophomore in high school, so I had seven years, enough time by anyone’s standard. Obviously I did not expect the translation to be all that good . Obviously I did not expect that a translation by a college senior would make anyone forget about Robert Fagles, whose translation was new that year and was being released as an audiobook read by Sir Ian McKellen. Obviously it would be just an exercise, I said; a real proper translation could take decades, by which time the world would be ready for an update to the Fagles edition.

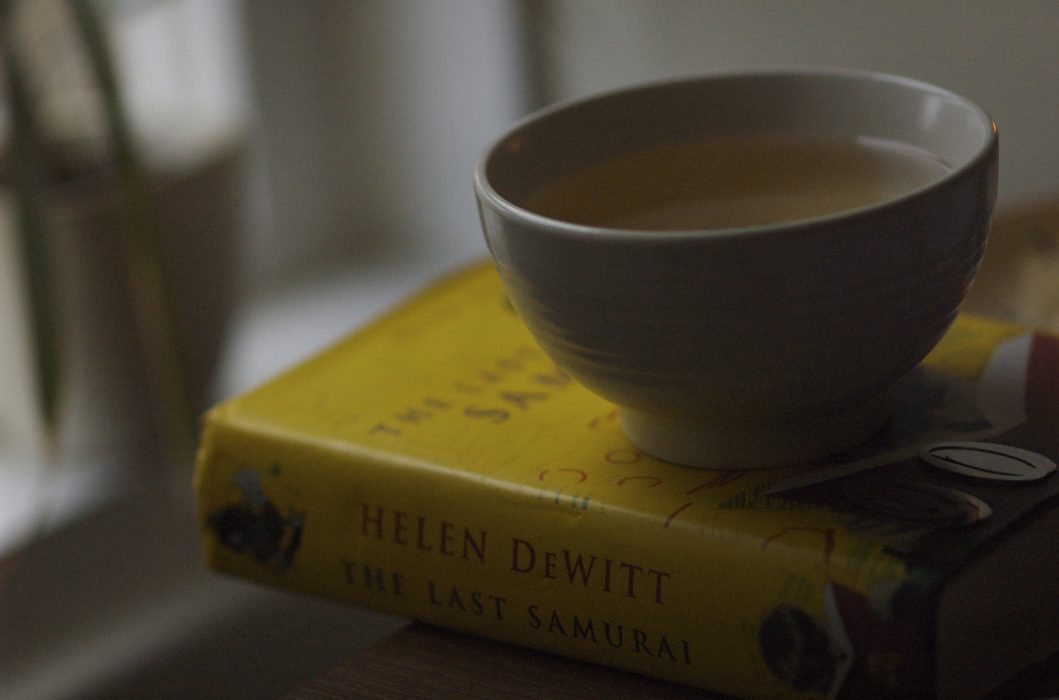

Books are the cause of so many bad ideas. The cause of mine was Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai , which came out in 2000, sold 100,000 copies, won every prize in sight, and then vanished . It has finally been reissued by New Directions, after having fallen out of print for fifteen years. It had dropped off my radar, too. But opening the new edition this week to find those galloping sentences and untranslated Greek and quotation-mark-free dialogue was like being hurled through a wormhole backward into my teens.

The Last Samurai came into my life like a bolt of lightning igniting a prairie fire. It told the story—and for no other book is a back-cover summary more futile or unjust—of Sibylla, a brilliant woman wasting her life typing print magazines like Pig Fancier’s Monthly into a word processor for £5.50/hour while raising her son Ludo, a prodigy barely out of Pampers. Aided by a VHS tape of The Seven Samurai , which she judges to be equal to seven fathers, Sibylla trains Ludo in the bushido of logic and reason, using great epics like the Odyssey and Kalilah wah Dimnah as guides . They eat thought like air. But as Ludo grows older, inhaling languages and literature and science like most children inhale small plastic toys, he becomes obsessed with the one thing he cannot teach himself: the identity of his father, a travel writer Sibylla baptizes “Liberace” for the lachrymose badness of his writing.

There’s more, but the point is that I was fifteen and a six year-old fictional prodigy became my pace rabbit. Ludo (and Sibylla, who teaches her son to love language for its precision and beauty, and hate irrational fools for their willingness to remain fools) were my cynosure, which they would want me to note comes from the Latin cynosura , from Greek κύνωσουρά dog’s tail, from kuōn dog + oura tail, also ‘Ursa Major’ — in so many words, my North star. The message of TLS —and its great beautiful lie—is that there is nothing prodigious about prodigy; it is only a matter of doing the work. All that year, I read TLS the way Ludo and Sibylla watched The Seven Samurai , no sooner finishing than starting right back at the beginning.

The essayist Helena Fitzgerald has written that “there is a particular way we love books that find us at exactly the right time, a love that swells beyond the dexterity of the writing or believability of the characters.” The Last Samurai was that book, but if I loved it I loved it in one of those sinister, unstable isotopes of love, the kind you radiate toward people so seemingly perfect, so brilliant, that you want to subsume them into yourself. The Last Samurai may be the most unabashed novel-of-the-mind ever written. Next to nothing happens. All of the conflict— all of it—is intellectual. The villains are glib artists who make beautiful empty things; the heroes are pianists who will subject a paying audience to seven hours of the same Chopin piece repeated fifty times until the audience actually hears it. Instead of inventing dramatic plot twists to make the intellectualism go down smoother—as if the reader were a child who can only consume medicine if it’s hidden in a scoop of ice cream—Dewitt invests pure thought with an elan and heat that crackles on the page. I loved TLS because it was everything I wanted to be—that it even existed was a miracle—and I hated it because it was already too late.

Most adults treat our own adolescence as something we wish we could fire into the sun. Maybe Rimbaud is right in saying on n’est pas serieux quand on a dix-sept ans, we are not serious when we are seventeen, but from ages fourteen to sixteen we are in mortal earnest. Whenever I think back on who I was then, an intolerable, arrogant child with no chill at all , I am rightly mortified. And yet, now that I’ve returned to Sibylla and Ludo, I see how badly I need that old arrogance back.

There comes a time in our lives when our hunger shifts from wanting to have something to wanting to be something. Like the mutant X-gene in Marvel’s X-Men series, ambition tends to awaken during adolescence, usually as the result of a triggering event. And for a few years—if we are very lucky and tolerated by those who love us—our powers feel limitless. The world has not yet taught us the painful science of moderating expectations, so art bursts out of us like solar flares erupting from the surface of the sun, reckless and uncontrollable and all out of proportion to our skill. I did everything: I wrote plays, I wrote novels, I acted, I sang, I gorged myself on Aristotle and Walter Benjamin, I fell permanently in love with James Joyce—I even wrote half of my college application essay in Finnegans Wake -ese. All I knew was that I finally had something I was willing to work for, and it was as if the laws of gravity had been abolished.

The laws of gravity soon reasserted themselves. I managed to pass into Greek II in the fall, but once in a class, I could no longer hide from the nightmare of noun declensions, and I never studied it again. Those early novels and plays I started were never finished because I didn’t want to make them, I wanted to have made them. I thought that’s how you made art. I was like Ludo, who thinks “what if I had the chance of having a perfect father and blew it because I forgot the mass numbers of the three most abundant isotopes of Hafnium?” I’d missed the sadness embedded in that sentence: the child with knowledge of everything except what that knowledge is for . Back then, it was easier to admit that I was not cut out for prodigy; I had been right from the start—I’d begun too late.

I am still an ambitious person. Yet with each little failure and false start over the last fifteen years, I feel the scope of my ambition narrowing: “Write a work of great literature” became “just finish the damn book”; “inspire people with writing” became “get someone, anyone, to give me some money for writing.” We all have these stories. They are how we learn to become the adults we dreamed of as adolescents. We compromise, go at our dreams piece by piece, one essay or story at a time. We remind ourselves it’s a marathon, not a sprint. And year by year, those dreams diminish. The adolescent fire dwindles, and dies.

But after years in secondhand hell, The Last Samurai has come roaring back into my life. And its song is still seductive to me. To be honest, I was a little afraid to re-read it. What if I’d been wrong? What if what fifteen-year-old Sam had taken for sheer genius was, in the cold light of adulthood, nothing more than glib, pretentious hoo-ha?

It wasn’t. If anything, it was better. My once-radioactive love for it has stabilized, calmed, smoothed—as all love must if it is to last. I’d never understood how casually heartbreaking the story is. I’d missed the aching pathos of Ludo’s guilt over having surpassed Sibylla’s power to teach him, followed by his gathering fear that his mother might commit suicide, as poverty and Pig Fancier grind her down. Not to mention his search for a surrogate father, which involves convincing men that he is their biological son—and which I find intensely hard to read. I linger over the tiny glittering gems of craft Dewitt has studded every page with, gazing at each of them as if through a loupe. I am still dazzled.

More than anything else, though, as I dive back into The Last Samurai I feel the old hunger returning. Once again, Helen Dewitt is out here giving not a single isolate fuck about anything but her own vision. Once again, Ludo is thinking If we fought with real swords I would kill you. And once again, I am fifteen, and I begin to feel the old confidence and disobedience shake themselves awake, like atrophied muscles lent new vigor. The difference is that somehow, in the course of the marathon, I seem to have become a writer. The muscles are coming back, but now I know what to do with them. I’m not too late. I’m bang on time.