On Writing Interviews

A Conversation with Kathleen Dean Moore, Author of ‘Earth’s Wild Music’

“Linking climate action and environmental protection to social justice action is essential. It is still possible to hope.”

As 2020 roiled into 2021, Kathleen Dean Moore camped with her husband on Oregon’s coast amid sand dunes and beach pines. They heard the roar of the surf from a raucous sea, and the wind shook trees that dropped pine cones on their tarp.

“It was glorious,” Moore says by phone. “We wanted to spend New Year’s immersed in the wild.”

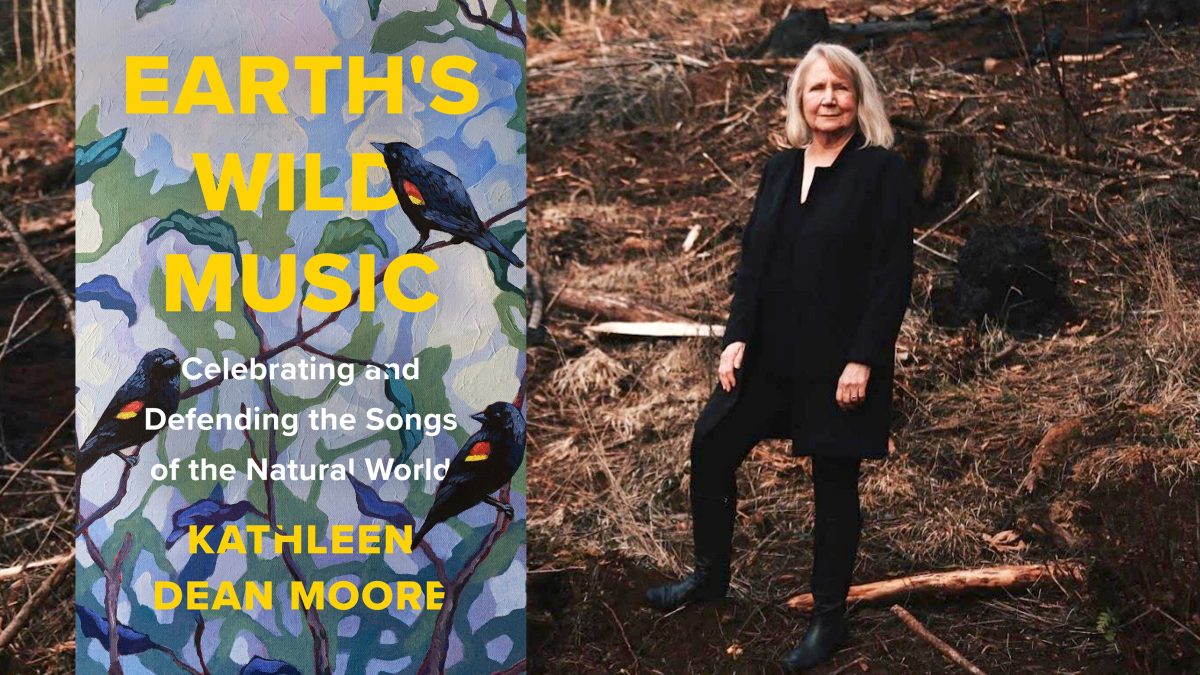

Moore, seventy-three, is a moral philosopher and environmental writer. Her new book, her eleventh, Earth’s Wild Music: Celebrating and Defending the Songs of the Natural World , is steeped in nature, brewing alternately with love and rage. “ In the fifty years that I have been writing about nature, roughly 60 percent of all individual mammals have been erased from the face of the Earth,” Moore writes.

The thirty-two essays, mostly written in response to the sixth extinction crisis (which says that the irreversible loss of species is due to human activity), move from lamentation for the growing silence of skies to reverie for life in the wild world.

Moore writes at the intersection of ode and alarm inhabited by the spirits of Mary Oliver and Rachel Carson. Part memoir, part call to arms, the book follows Moore’s treks into nature on an Alaskan island, where she spends her summers, and in Oregon, where she lives the rest of the year. She hears the “huff huff” of bears, the boom of a calving glacier, and yellow-headed blackbirds that “make a grating, buzzing noise like barbed wire caught on a gate in the wind.”

Along the way she introduces the reader to the one-toothed cannibal tadpole, trumpeting humpback whales, and a meadowlark that sings “like a flute underwater.” Fact boxes at the end of each essay dispatch data: the status of loons, spiders, and bats; the relationship between migration timing and climate change; the devastation wrought by recent wildfires.

With animal sounds and textured descriptions of the natural world, she emphasizes the importance of listening, “for safety, for beauty, for wholeness,” so as to be fully alive beneath the unbearable weight of loss. She argues on behalf of love and empathy. A mission statement guides her writing life: “For the sake of the beautiful, innocent children of all species, I stand against the corporate plunder of the planet.”

A scene early in Earth’s Wild Music haunts me: As Moore walks with her grandsons through the woods, they happen upon a dead bald eagle lying on its back. While the boys stroke its beak, Moore lies on the moss beside it, looking up to the sky to see what the eagle might have seen in its final moments of life. “I lay there a long time,” she writes, “looking east, listening to the wind and the water-smack. Thinking.” This radical empathy permeates the book, as she moves inside and out of the worlds of dying species. When a creature dies, Moore writes, so does its song.

Moore and I corresponded by email and spoke by phone about playing music on a cactus, about loneliness, about living like a bird during the pandemic, and about the culpability of corporations. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

Book cover by Counterpoint

LT: What is your writing process?

KDM: I do most of my writing in journals in the field or, more often, on the water. If it’s raining, I sometimes write with my hand and journal inside a ziplock bag. Then I bring the free-written words home and revise on my laptop. I number the revisions, so I can tell you that the average number of revisions before publication is seventeen.

LT: You can play “Ode to Joy” on a saguaro cactus, but do you also play traditional musical instruments? Do you listen to music while you write?

KDM: I can play the piano as well as most people who refused to practice when they were children, scowling at the keyboard with their hands clenched in their armpits—which is to say, very poorly. But I grew up singing four-part harmony, and I love to sing. This past Christmas, my extended family tried to sing Christmas carols by Zoom, and it didn’t go well—but it still made me weirdly ecstatic to be trying to create some harmony, even if none of us got to “laughing all the way” at the same time. I think it has to do with creating a resonance with other people you love—a true buzz.

I don’t usually listen to music when I write, because I can’t listen with only half my mind. The music pushes in like a king tide and the writing floats off unmoored.

LT: There is a lot of symphonic, collective activity described in the book, but also a lot of loneliness. Do you feel lonely when you’re listening to nature?

KDM: Ah, you have found me out. Yes. From a purely scientific point of view, animal calls are often calls of yearning. A thrush call in spring: Will you come near and love me? A wolf call in winter: Where is everybody? A whale in a Hawaiian bay: Big boy looking for love . Once animals are paired, they become very quiet. But there’s something more than this. Beauty itself can be lonely. I don’t know if it’s because there is a strong urgency to complete the experience of beauty by sharing it. Oh, I wish my children were here to hear that . What is it about a human being, that urgency to share?—Listen! Do you hear that call?

LT: You describe “living like a bird” during the pandemic. And you describe the diminishment of various species. Did the quiet of the pandemic, with people and industry on lockdown, affect the wildlife and nature in your region in any positive or unusual ways?

KDM: At first, I thought the birds were singing more brilliantly; then I learned that the volume of birdsong had not increased, but the volume of traffic had decreased. But what strikes me now, and what I am certain is a lasting effect of the pandemic, is people’s discovery of how very much they need what Gretel Ehrlich called “the solace of open spaces.”

The trailheads in my community are packed with cars, and more parking spaces are going in all the time. The bike trails look like the start of the Tour de France. The sidewalks are full of people, even in the pouring rain—especially in the pouring rain—walking their dogs or tilting their faces to the sky. I’ve never seen anything like it. You can’t get up early enough or stay up late enough to escape the crowds at the best goose-landing spots.

Where did all these people come from? And what do the swans in the roadside ponds think of the gawkers? What do the deer think of the people parades? When the pandemic is over, I hope people will remember how the wild places saved them.

LT: Is there a specific takeaway from the retreat of humans and industry during the pandemic that shows how we might better coexist with our natural world?

KDM: We learned that it’s possible for human beings to change quickly—to stay home, to give up the European vacation, to grow our own food, to telecommute, to live more modestly. Each of these had the effect of reducing carbon pollution, not so hard after all. We learned how much joy and comfort we take in the natural world, a refuge, a safe space, a broad expanse of land and light filled with birdsong.

We learned that we can be quiet. Our noise is an act of aggression that we have unthinkingly turned on the world. We have learned to listen. Most important, we learned we are vulnerable to the forces of nature. Not king of the mountain anymore, but flesh-and-blood creatures of the Earth.

Photograph courtesy of Kathleen Dean Moore

LT: You describe a number of species that you’ve observed in decline—frogs, whales, and owls, for example. Can you point to one that affects your daily life?

KDM: Twenty years ago, my husband and I dug a pond in an old feral farm field next to the Marys River in Oregon. Our goal was to provide habitat for two endangered species—the western pond turtle and the red-legged frog. The red-legged frog is the only frog I know that sings underwater. To listen to its chorus, we had to sink lawn chairs in the shallows and drop in a microphone on rainy days in spring. Gwaaap .

For a number of years, we heard them often, but less often this year, and I am afraid for them. The hotter, drier summer emptied the pond before their tadpoles could develop into froglets and hop to safety. As for the western pond turtle, we have seen no sign of them. We try to stay focused on the possibility they will come.

LT: Ours is a country that seems perpetually busy. I wonder how you’d answer this question (one you wrote): “How can we be fully alive if we don’t pause to notice, and to celebrate, all the dimensions of our being, its length and its depth and its movement through time?”

KDM: If I were an evil genius whose goal was to strip the humanity from humankind, to strip them of the natural pleasures of being closely connected to time and rivers (as they say), I would design an economy in which parents couldn’t feed their families without working two or three full-time jobs, in which mothers had no help in the work of the household, in which fathers were disdained and underpaid for the unsafe work they did. I would convince people that what they needed, they didn’t really need (food, rent); I would convince them that what they didn’t need, they really did need (Ford pickup truck, football); and I would convince them that they did not deserve what governments were pledged to provide them (safety, clean air and water, a homeland).

Then I would sit back and laugh, because they would be too busy to connive or complain, which is the whole point of the exercise. Damn.

LT: You write that the answer to hopelessness is to do what you think is right. But many people won’t start a bicycle collective or cook with solar power. What do you suggest to them? What is one of the largest actions people could make to change the course of loss? What is one of the smallest?

KDM: May I first humbly object to the question?

LT: Of course.

KDM: Big polluting corporations love the “fifty things you can do to save the world” lists, because they redirect blame for climate change and ecosystem collapse onto personal decisions. They thus outsource their shame onto ordinary people, whose decisions have a small impact, and away from their own cynical devastations, which have a huge and multiplying effect.

Polluting corporations also love the assumption that people need to act alone. “What can one person do?” people ask me. The answer is “Stop being one person.” Communal, community-building, collective work, large or small, is much more effective, and much more fun. The most effective first step in combating loss is to pick up the phone and call a friend: What are we going to do about this? The most effective first action is the potluck: How can we work together?

The most fun I’ve had as a climate activist was the day eight of us stood on a rock in an icy inlet and let the tide rise right up over our heads. The accelerated video was a great demonstration of the effect of global warming on ocean-level rise.

All that said, here’s the best advice I’ve heard for aspiring activists. It comes from Joanna Macy. “You don’t have to do everything. Do what calls your heart; effective action comes from love. It is unstoppable, and it is enough.” What calls my heart is calling out the corporations.

Photograph courtesy of Kathleen Dean Moore

LT: Alaska and Oregon sound like beautiful places to live in nature. What do you advise city people to do to hear the music of the earth amid the asphalt (other than leave town)? How might families not raised by naturalist parents like yours pass along to their children a way to commune with nature?

KDM: I grew up on the southwestern edge of Cleveland. My dad was a naturalist in a skinny little strand of park under the final approach to the Cleveland Hopkins Airport. People washed their cars in the stream while their kids waded around. But there were fossils in rocks in the ledges and salamanders under fallen leaves, and between the jet contrails, there were vultures.

What made all the difference for us was not a pristine wilderness to explore, but an adult to show us the nature that was all around us, to say, “Look. Listen.” This is a great gift that each of us can give to children, no matter where we are or how much or little we know about birdsong.

LT: What do you want a Biden administration to do immediately to address the climate crisis, other than rejoin the Paris Agreement, which they’ve said they’ll do?

KDM: The list is long. Linking climate action and environmental protection to social justice action is essential. Restoring and expanding the protections that the Trump administration destroyed is urgent—protections for migratory birds, clean water, public lands, Indigenous lands, the Arctic plains, forests, soil, and especially frontline communities.

Whereas Trump’s environmental decisions seemed to be based on vengeance, greed, and spite, we have a new chance to design environmental policies based on visions of eco-cultural thriving and environmental justice. Crazy, after all these years, and all these woundings, it is still possible to hope.