On Writing Debut

How This Lawyer Learned to Call Herself a Writer

My vision of a writer has always been someone quiet, someone introverted, and—especially—someone white.

“What do you do?”

It’s one of the first questions we hear at parties, meeting someone new. For most of my life, this has been an easy question to answer.

“I’m a lawyer.”

That’s the way I’ve answered for fifteen years. For the three years before that, I was in law school. For the twelve years before that, in answer to the junior version of that question—“What do you want to be when you grow up?”—I always said, “A lawyer.” (For a while in childhood, the answer was “a ballerina,” but then I hit puberty and no longer had a ballerina kind of body.)

My seventh-grade history teacher, Ms. Murray-Gill, left teaching and went on to law school the year after I was in her class. She was a black woman about ten years older than I was, and looked enough like me to be my older sister. Seeing her on that path made me—a young, book-obsessed, chatty black girl—realize that such a path was open to me, too.

Law school called to me immediately: I’ve always loved history and politics; I watched the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings just a few years earlier with both confusion and anger; I grew up in Berkeley, so political protest and activism was part of my life; I basically memorized Schoolhouse Rock. I’ve always been argumentative, so when I told my family I wanted to be a lawyer, their immediate response was: “That sounds right.” I put my foot on that path at age twelve, following my beloved teacher and mentor, and never wavered from it.

Until about seven years ago, I never had any ambition to become a writer, despite how much I’ve always loved to read. Family legend says I learned to read at age three, and since then there have probably only been a handful of days when I haven’t read for pleasure. When I moved from the West Coast to the East Coast and then back again, I spent a small fortune shipping boxes of books across the country. Many of my closest friendships—from childhood to the present day—started with bonding over a book.

I now wonder why no one in my life ever suggested writing to me. I wonder, if they had, would I have rejected the idea out of hand? My vision of a writer has always been someone quiet, someone introverted, and—especially—someone white. I saw this pattern in so many of the girls in the books I read and loved as a kid: Anne, Emily, Betsy, Harriet, Claudia, Meg. When I turned those childhood favorites over to look at the picture of the author on the back, they almost never looked like me. There were books about little black girls, but they were almost exclusively about little black girls during times of struggle: during slavery, in poverty in the early twentieth-century South, during the civil rights movement. I wanted to read fun books about smart girls who lived in cities and did exciting things with their friends. I couldn’t find books like that about black girls.

After I’d been a lawyer for about eight years, I found myself longing for some sort of creative outlet. The repetitive, structured, spreadsheet-oriented nature of my work often made me feel stifled. I can’t sing, I can’t draw, and while I still love ballet, I didn’t feel an urge to return to dance class. After a few tentative conversations with some of my writer friends , I started working on a novel—a young adult book about a smart black girl who lived in a city. The sort of book I wished I’d been able to find when I was young.

At first, I told barely anyone what I was doing. It seemed almost embarrassing for someone like me to go home from her legal job every night, sit on her couch with a laptop, and work on her book. Why had I ever thought I could do this? I didn’t go to school for writing; I haven’t even taken an English class since my senior year of high school.

But I loved learning about and developing characters, the process of frustration and brainstorming and epiphany. I read books on writing, and closely reread a number of novels to study how other writers wrote dialogue, quiet moments of connection, fights. The more I threw myself into learning how to write, the more I began to wonder whether my novel could actually be published.

About a year after I started writing, I met Sara Zarr, a writer I’d been Twitter friends with for years, and whose work I’d read and reread. Over drinks, she said, “I realized I don’t really know what you do. Are you a writer?” I hesitated. She looked at me. “You write, don’t you?” she asked. “If you write, you’re a writer.”

It’s easy to know when to call yourself a lawyer: Did you graduate from law school? Congratulations, you’re a lawyer. But how do you know when to call yourself a writer? How did I know?

I started trying to call myself a writer after that conversation with Sara—only in my head, never to anyone else. I finished that first book and started another, yet still told very few people what I was doing. I would bring my laptop on business trips and work on my novel in the hotel at night. More than once, I brought my laptop on vacation with friends, escaping to write and telling them I had “work to do.” I told a few friends that I’d written a book while I was in the process of trying to get an agent for that first novel, but after all of the agents I’d queried eventually passed, I stopped talking about it.

During a health crisis, I took a long break from writing fiction but tiptoed my way back into writing by publishing short pieces online. I wrote about books, and food, and celebrities I adored, and while I still had trouble thinking of myself as a writer, all of that practice helped work my writing muscles.

The orgy of reading I did that year did, too. Before that year, I hadn’t read more than a handful of romance novels since I was in high school, but while I was sick, and then recovering, I dove into a pile of them. Finally, I talked myself into starting a romance novel after a push from a friend. I was still working well over sixty hours a week on my day job, but I snuck away to Starbucks to write for thirty minutes at lunchtime and wrote for an hour or two every night when I got home.

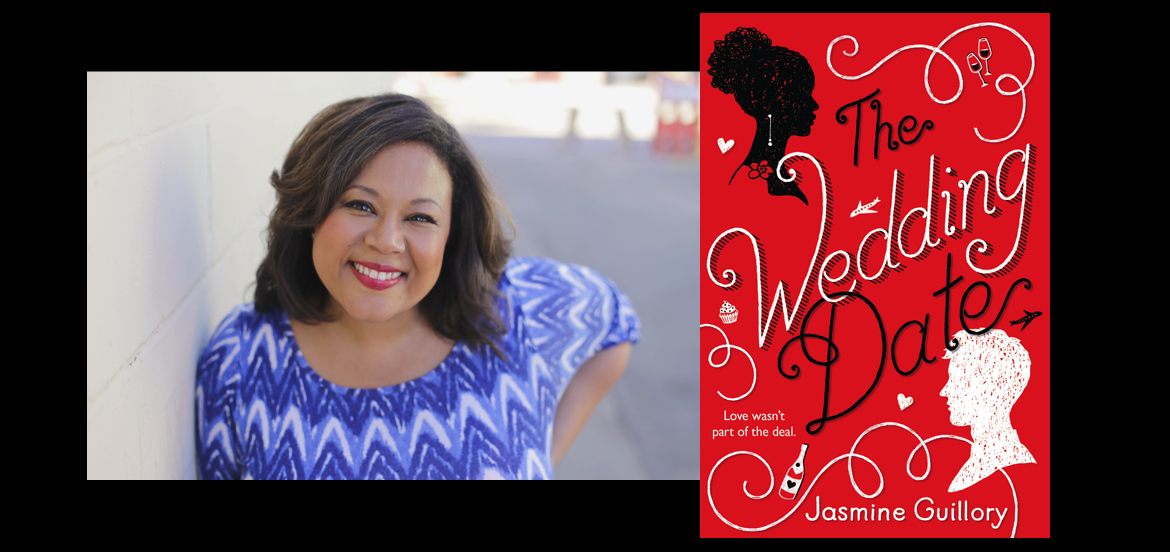

Berkley Books, Jan. 2018

That romance novel got me an agent, but most of my friends and family still had no idea until I announced my book deal. Overnight, it got a lot easier for me to call myself a writer. Then, at least, I had something to point to that actually made me a writer. But part of me still felt like I was pretending. Even as I went to gatherings with other writers, people who knew and saw me as a writer first, I thought of them as the real writers. They all had long writing resumés and seemed so established, I had no idea why they were letting me crash their parties.

Last summer, during a weekend away with friends, I woke up early to write for two hours—something I’ve done many times before—and I realized that I was better at being a writer than I’d ever been at being a lawyer. As a lawyer, I knew I sometimes procrastinated, but as a writer, I was fully committed to my work. And I spent years grinding away at it in private with no reward, no payment, no one making me do it. One glance at my cluttered apartment, with books piled on the floor and necklaces hanging from every door knob, shows how disorganized I can be in other arenas of my life—but as a writer, my search for an agent was methodical; my plot outlines are detailed; my character spreadsheets are updated frequently.

I know I’m a writer—not just because I write books, not just because I love it, but because I’m better at being a writer than I’ve ever been at anything else.

Now, when I’m asked what I do at parties, “I’m a lawyer and a writer” comes out a lot easier. I love this job more than I’ve loved anything else. And I love hearing from all the other people who hide away to write—on lunch breaks, on vacations, at home late at night—and whisper their secrets to me. You’re all writers, too.