Columns Digital Hope

For a Freelancer in the Gig Economy, There’s More at Stake Than a Paycheck

Freelancers are turned into abstractions rather than people, recontextualizing the social relations of work in new ways.

A woman in the office I work at has been calling me “Gerald” for about a year. My name is not Gerald.

I tried telling her this a couple of times, but she continued to say, “Hi, Gerald,” when I would see her, so eventually I just stopped correcting her. Doesn’t seem worth it. I only work here a few days per week. Technically, I’m not even an actual employee. Instead, I’m what’s called an “independent contractor”—hired by the company, but facilitated via a third-party digital platform, in my case Upwork.

Upwork is a global freelancing app, intended to connect contractors (writers, social media coordinators, anything, really) to employers. This can mean many different things. For me, it means that I come into the office for this company as a regular employee, with a name badge and a (temporary) cubicle, and I interact with everyone there like I have the same benefits and resources as they do. In reality, I don’t work for the same people and my presence is tenuous.

Upwork claims to be the largest freelancer marketplace in the world, with twelve million freelancers and five million clients (though the accuracy of these numbers is unclear ). But there are countless competitors, including Fiverr, Hubstaff Talent, and Freelancer.com. With no clear agreement about which workers are technically part of the gig economy , it’s difficult to know for sure how many there are, but one estimate puts the number at over 57 million Americans. In that sense, I don’t have to tell you that the economy has moved significantly in ways that prioritize freelance labor and utilize digital platforms.

This reorientation of our lives to center digital platforms for services and work is always happening and ongoing. CNBC reported that Uber and Lyft drivers—ostensibly in business for themselves, and all the freedom that supposedly brings—earn between $12 and $15 an hour after costs (Uber’s 25 percent commission, gas, repairs, etc.), which is certainly not a living wage. According to a survey conducted by Freelancing in America , which is run by Upwork itself (a red flag, perhaps), 31 percent of American freelancers earn $75,000 or more annually, from a sample size of 6,000 (62 percent of respondents were white, and the vast majority are under thirty-five).

Moreover, Freelancing for America’s definition of freelancer also includes what is called “diversified workers,” which means they mix a day job with freelance work (they take up 31 percent of America’s freelance pool), and even more bizarrely, “freelance business owners,” people with one or more employees that still identify as freelancers (6 percent).

Even if we accept those numbers to be accurate, that leaves many freelancers that earn far, far less. Moreover, the pressures of the so-called ‘gig economy’ means that you often need to be hustling fifty, sixty, seventy or more hours per week, at all times, to make ends meet. (The same report says freelancers put in 1.07 billion hours of work collectively per week, up 72 million hours from 2015).

And in April, the Department of Labor announced that gig workers should be classified as independent contractors, dismissing the movement to get them recognized as employees. This was a clear indication that the government sides with the platforms, many of which have been faced with lawsuits over wrongful classification and other worker offenses.

The DOL claimed that the decision was due to the amount of “control” freelancers have over what work they do and who they do it for. In practice, freelancers know that reality is far more complicated. For example, my gig economy job is predicated on the assumption that I exist within an established hierarchy and that I am there to serve particular needs. But my contract can only ever be extended by a few months at a time, meaning I am more or less “on probation,” as a normal employee would be, only indefinitely.

I’ve been lucky enough to have mine extended several times, but freelancers are always on that cusp. Once a job ends, it’s not like a buffet of appealing options appears, as the DOL seems to envision. These are often financially desperate people searching for any short-term position that can make use of their skills.

What’s really happening here is that small businesses and giant brands alike have realized how vast the cost difference between hiring employees and simply getting some freelancers to take care of a job temporarily. Right now, I’m doing social media work for a tech company that barely has anyone else working on social, which means I am largely responsible for the company’s entire social media plan (scheduling, drafting, and developing posts across all channels) while only working three days per week. Rather than hiring full-timers to consistently have a full approach, employers think, why not hire someone part-time to do exactly as much as you need?

This “control” or “flexibility” is a trade-off that these workers make in exchange for no paid sick leave, no insurance, no laws for overtime or wages, and certainly no unionization ( though many groups are trying ). Ephrat Livni, for example, called the gig economy “corrosive” and “dangerous.” She put simply, “Companies can make more money and incur a lot less liability classifying workers as independent contractors, so they do.” Even a Federal Reserve report on economic well-being that was released in May showed that gig economy workers are struggling much more than the average laborer. This led Vox to declare that the gig economy is “largely based on exploitation.” Cost-cutting via freelance work has become the core of the modern economy’s profit strategization. Put simply: We’re getting fucked.

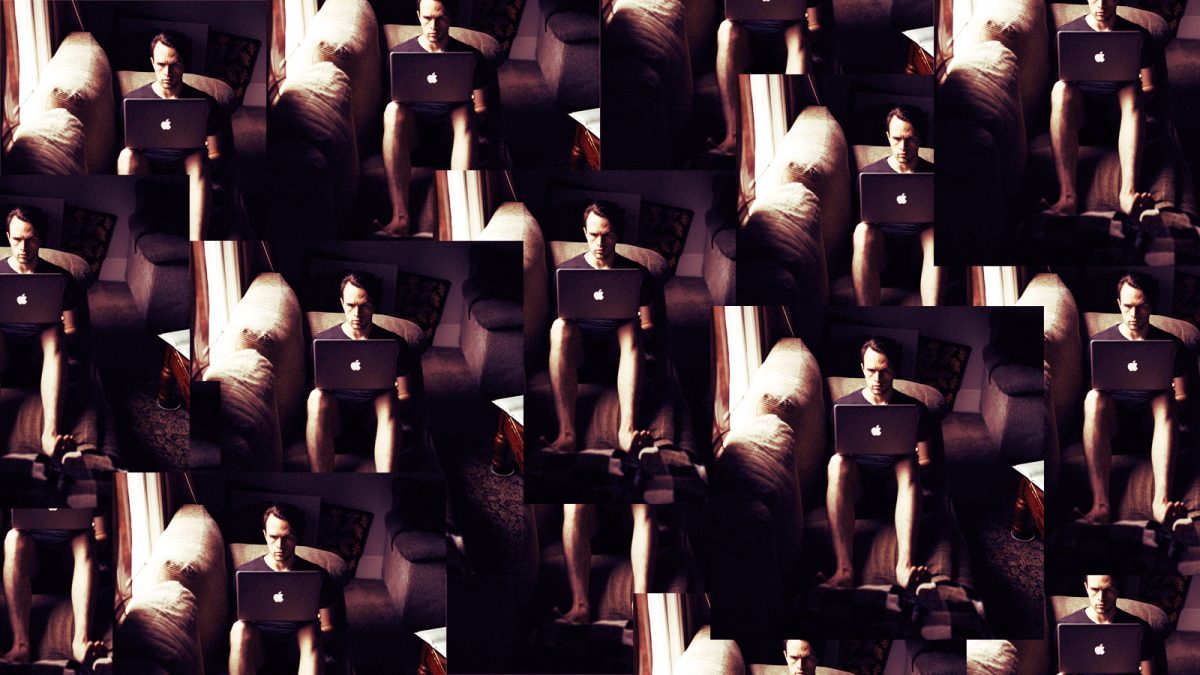

The result of all this is a profound sense of alienation. I write as a freelancer, and it’s been well-established how unreliable it can be, with late payments (or payments that never come) and increasingly low standard rates. I work for myself, which is great—I set my own hours, can work in my boxer briefs at home, and more or less choose what sort of stories I want to pursue. At the same time, I also work for every editor I can find, re-starting those relationships each time and unable to build any kind of long-lasting stability. Even more isolating, I’d say, is my Upwork job, for which I could potentially be rated for the quality of my work in social media, possibly impacting future gigs.

The illusion of control is a top selling point ( Lyft : “Want to be your own boss?”), and also the biggest lie. By default, Upwork implements a system that takes a screenshot of your entire screen every ten minutes (though never precisely, to avoid predictability), ostensibly to make sure you’re on task. This can be turned off, but you would have to ask your “employer” about it, which many freelance workers might be uncomfortable doing, considering how tenuous their position already is—there’s always someone else waiting to take on the same role. While the folks at the company I work for are nice enough, there is an undeniable atmosphere of separation and even a dystopic Big Brother-esque surveillance culture.

Working for a platform means engaging in a unique form of emotional labor, in the original sense of the phrase. You are expected to be grateful for the opportunity, and to look and act like part of the team, even though you are not. Moreover, workers on platforms like Upwork are at the whim of feedback and rating systems, just like Uber and Lyft drivers, which makes me think about how the gig economy is the ultimate capitalist dream come true.

As Harry Braverman wrote in 1974, “The ideal organization toward which the capitalist strives is one in which the worker possess no basic skill upon which the enterprise is dependent.” The profits of a graphic design firm, for example, are not reliant on a particular designer’s abilities or output, “but rather where everything is codified in rules of performance or laid down in lists that may be consulted (by machines or computers, for instance), so that the worker really becomes an interchangeable part and may be exchanged for another worker with little disruption.” The intervening years have allowed this nightmare to become our reality, wherein companies rely more and more on worker interchangeability. They commission individuals for one-off jobs and maintain their organizational flow by building those turnovers directly into their structure.

Freelancers are turned into abstractions rather than people, recontextualizing the social relations of work in new ways. Some of that comes from the impersonal nature of utilizing a digital platform for that process. The act of hiring, firing, evaluation, everything, is all done via an impersonal platform. Freelancers are turned into abstractions rather than people, recontextualizing the social relations of work in new ways. The platform isn’t simply an intermediary, it is the entire infrastructure within which these jobs exist.

Workers on Upwork are often required to “bid” for jobs, crassly mimicking a regular competitive market (even drawing comparisons to gamification , as though yearning for personal best achievements is the same thing as being incentivized into scoring highly at your job to secure more work). Soon , freelancers will even have to pay to bid for a job on the platform. Upwork features a system of “Connects,” which used to be free tokens that you would use to apply for jobs by spending up to six “Connects” at a time.

Formerly, you were given sixty “Connects” for free and could buy more if you ran out. Now, they will cost fifteen cents each from the beginning, meaning that each bid will cost freelancers. Particularly in-demand jobs (requiring at least six “Connects”) will cost more, with (of course) no guarantee of even being contacted. This structure, supposedly built on user choice. is sometimes termed as “management by customers,” particularly by Silicon Valley types using language that appeals to investors and regular folks alike. In practice, it’s management by platform.

As the sociologist Alessandro Gandini argues in a journal article about the consequences of the gig economy, this state of affairs is nothing new. It’s merely an intensification of capitalist desires facilitated by new technology. Moreover, “digital gig work platforms seem to be designed as organizational models that ‘invisibilize’ the managerial figure—which remains hidden and inaccessible for workers as it sits behind the screen of a digital device and a set of anonymous notifications—and prevent workers from socializing with each other, thus reducing the potential for resistance and unionization.”

Again, we are made into abstractions, working for an abstraction. I think the lady that calls me “Gerald” is probably just a little old, but she helps demonstrate how these calculated ambiguities play out in the real world, too. Capitalism lusts after a homogenous, easily substitutable, and unidentifiable workforce. These platforms merely provide them with the ideal tools necessary to make that happen like never before.

There have been some pushes for union efforts and one can take advantage of organizations like the Freelancers Union . Still, it remains true that the very condition of working for a digital platform makes these efforts all the more difficult than they already are under normal circumstances. The social reality of freelance work is being leveraged and weaponized to make the increased individualization of work seem not only tolerable, but desirable .

To conclude, then, please share this article so I can point to its impressive metrics when attempting to get another one published. All I have is my reputation.