Catapult Extra Excerpts

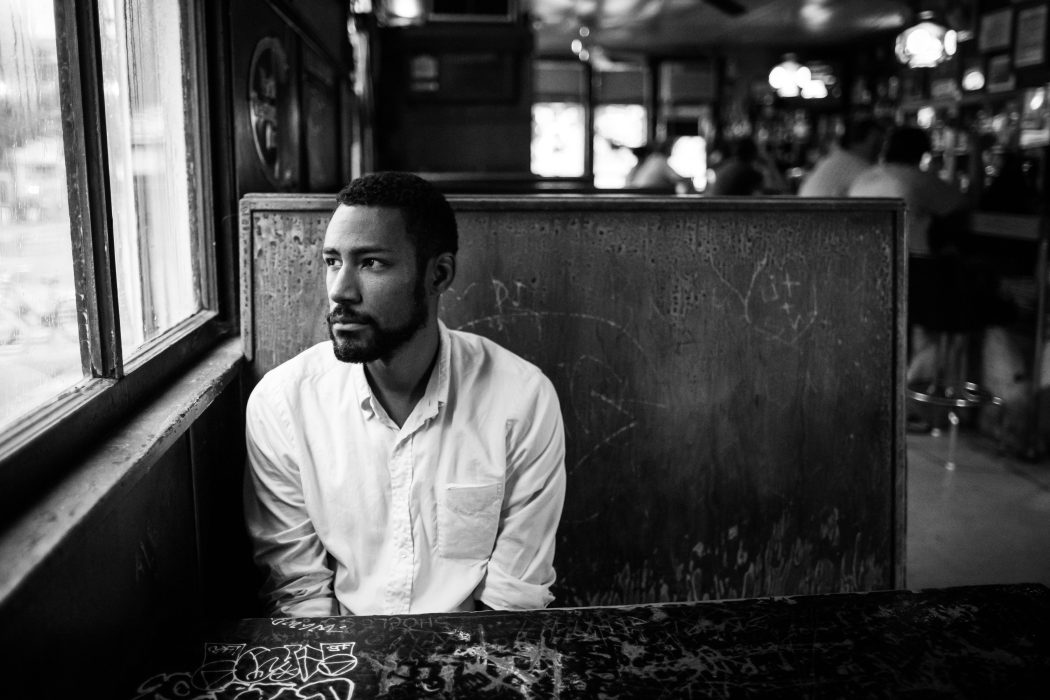

A Conversation with Andre Perry

“I wanted a way to talk to readers the way that I can only talk to my wife.”

My personal fascination with rapper Kendrick Lamar, ever since I first heard his album good kid, m.A.A.d city , has bled into creative endeavors, a fandom I’ve recently converted into literary criticism . It seems Kendrick’s art inspires and motivates the creation of more art, and more conversations.

This April, we published “Americana/Dying of Thirst,” an essay by Andre Perry, centered around a Kendrick Lamar concert performed in Iowa City. The epistolary essay is a love letter addressed to Emma, Andre’s then-girlfriend (now his wife), which briefly chronicles the concert, where Andre was in attendance amid “the roar of almost two thousand white people,” and where he ponders the dissonance between Kendrick’s self-reflective, political verses and an audience who might overlook the message his music offers.

I chatted with Andre Perry via Google Hangouts, where we talked about our shared interest in Kendrick Lamar, the love letter as a literary form, and the current state of the personal essay.

*

Mensah Demary: I figure we can start with Kendrick Lamar himself. In broad strokes, what is it about him, and his music, that gravitates you toward him?

Andre Perry: I love Kendrick for many reasons. It’s likely difficult to explain all of those reasons in this space and time but I’ll try my best to focus a few key points. For one, I deeply respect how seriously he is taking his art. His attention to lyricism, to flow, to the music, to reinvention, to taking chances, is pretty extraordinary. I am not just comparing him to other rappers but other musicians. There is so much tired popular music right now—as there always is—but Kendrick, who is working with a wide, growing audience, doesn’t seemed concerned with watering down his music to make it more palatable for the masses. On the lyrical front, I am intrigued with his commitment to a blend between sharp narrative storytelling and more almost essay-like reflections on the world around him. With good kid, m.A.A.d city , it seemed like he constructed this expansive narrative over the course of the album just as a means to reflect on a number of topics regarding the life he sees living in Los Angeles. But of course in between those lofty thoughts are great rhymes, dope beats, and a lot of humor.

Mensah Demary: It’s interesting when I listen to his lyrics because I tend to believe everything he says. He somehow has earned my trust as a narrator, in that even if he’s taking some creative liberties in his lyrics, which is fine, I still “believe” him. He has an authority in his voice that few current rappers exhibit, no matter how hard they try.

Andre Perry: His voice is amazing. Both in the live and studio settings. In the studio, it’s my assumption that he spends a lot of time working on exactly how his voice is going to sound: as in how they record his voice, how many vocal tracks he layers, how they compress it, how they mix it, and so forth. The process of recording rap vocals is so important because those voices are what seduce us, bring us into a rapper’s world, and make us believe them. I mean, Guru or Q-Tip or Prodigy or Missy, all of them just seducing listeners into their world.

Mensah Demary: You attended a Kendrick concert in Iowa, which was at the heart of your piece with Catapult . In the piece, you exhibited some anxiety regarding the scene: Kendrick, black and from Compton, performing in front of thousands of white college kids, and you even felt a disconnect in his music, between hearing it in headphones and watching him perform live.

Was this anxiety/distance specific to the Kendrick concert? Have you felt it at other performances where the audience was mostly white?

Andre Perry: I think there’s always going to be anxiety when you’re black (or anyone) in a room and hundreds or thousands of white people are saying the n-word. That was a particularly heavy moment at the Kendrick concert but it served as an open door to think a little more critically about some bigger issues that aren’t necessarily new, like why do some white people love this music so much and can get so caught up in the moment at the concert or in their car or at the gym but when it comes to seriously discussing policy or legislation that affects the lives of black and other disenfranchised people they are like, “I don’t want to talk about that,” or “I don’t see any problems,” or “Please stop complaining,” or “That’s nice, but all lives matter.” I mean, are they listening to the lyrics? Is anything in the immediate context or subtext resonating with them? I am not even necessarily hating on them—I am legitimately interested in knowing how they cherish this music but not the culture and its people at large.

I have definitely felt such discomfort at other concerts. I live in Iowa and I go to see a fair amount of rap concerts, so I end up in a lot of spaces with black rappers and white audiences. Though, I realize that’s not just happening in Iowa. I saw Vince Staples recently in a smaller club in Iowa City. There were maybe four hundred people there. His show was great but in between songs he had some next-level stage banter. I am a bit older so I’m never at the front of the pit anymore but there were some black people up front mixed in with the white kids. Vince navigated his mixed audience really well. Some white kid upfront felt comfortable enough to say the n-word in between one of the songs—I didn’t see his face but I just pictured him laughing, feeling like it was all in good fun—but Vince put him in his place. To paraphrase, he was like, “I will fuck you up outside when this show is done.” That was the end of that nonsense. The show went on and everyone got down.

And I have to note that he acknowledged and thanked his black folks for coming out to see him in Iowa.

Mensah Demary: Your Catapult piece is in the form of a love letter from you to your girlfriend. Why that specific format?

Andre Perry: The “Dear Emma Letters” is a series of essay/letters that I’ve been working on for awhile. The Kendrick piece is just one of them. The first one dates back to 2008. I literally typed up a letter and mailed it to my girlfriend—now my wife. I chose that format because it allowed me to consider and reflect on issues with a different voice and perspective than if I wrote a traditional personal essay. I am able to access a rawer emotional depth with the letter format. The more traditional personal essay format allows writers to display their intellect or literary smarts on the page but these letters, I think, value emotion more than intellect. I wanted a way to talk to readers the way that I can only talk to my wife.

Mensah Demary: Just curious: what are your thoughts on the personal essay in general, namely the ones often published online?

Andre Perry: I am an essayist so I am very much down with the essay as a form. It allows an incredible amount of freedom for creative writers to posit ideas, narratives, information, reflections, insights, and even other elements of other mediums onto the page. And essays aren’t limited to the written word; the elasticity of the form manifests itself via radio, podcasts, and film, too. We have witnessed so many mutations in the essay over the last 10-15 years. There’s been an explosion in how writers are co-opting, reshaping, and celebrating the form. In terms of what’s published online, I don’t know if I can put everything into one bucket; there are so many different types of essays that appear on websites ranging from opinion pieces to experimental video essays. Regardless of form, the work is ultimately good or OK or bad.

I have particular tastes—styles that I am more inclined to like, but I don’t get caught up in the form and genre wars. I find those arguments petty, even offensive: people hating on an essay because it’s not narrative enough or people hating on it because it’s too narrative or it’s too emotional and not intellectual enough. In grad school I had to endure endless conversations between fiction writers, poets, and nonfiction writers all questioning each other’s chosen craft—there appeared to be a heightened tension between some of the fiction and nonfiction people. Look, I don’t care what kind of essay you’re writing or whether it’s a short story or a hybrid form: Your shit’s roses or your shit stank. If it’s stank then go back and find a way to make it smell better. And if you like that stankness, well, that’s cool too.

Mensah Demary: I think that’s a mic drop answer right there.

Andre Perry: Haha . . . Sorry that’s just where I’m coming from.

Mensah Demary: No, I love it. I completely agree with everything you’ve said, and it needs to be heard. There’s something to be said about the proliferation of the essay form in general, but the conversation is often steered toward the quality of the essays.

I often fall into the “thinkpiece” trap, throwing the word around as if it’s a pejorative. But it’s not even that deep. Either you dig the piece or you don’t, as you said.

Any upcoming projects you want to share?

Andre Perry: My band just finished a record so we are in the process of playing shows and supporting it. That will happen over the next year. On the writing front, I am revising the draft of a book. The piece I did for Catapult is in the book. I thought I had finished it last year, but I was mistaken, and I am glad a few close friends offered some key feedback to help push me into the next draft. That said, I think it’s close. I think. There’s also a fiction project about Iowa that I’ve been taking notes on, but it’s still a few years from really being something tangible. I am always in the middle of something and there is never enough time, but I refuse to lodge a single damn complaint: I am lucky to even be doing this at all and to have anyone, I mean anyone—even on my street corner panhandling level—taking the time to pay attention.

Just one more note on the topic of black alienation at concerts. We talked a bit about the feeling of seeing a black rapper in the midst of a white audience but I also don’t want to forget two other kinds of experiences: seeing white artists with a lot of other white people, as well as seeing black artists playing some form of indie music in front of mostly white crowds. My friends and I find ourselves in those situations frequently. It can be both exhilarating and frightening to be at these big concerts with thousands of white people submerged, due to no fault of their own, in group-think mentality. You’re almost like, “If something shifts there’s no telling what all of these people will do and I am the first one to go.” But there is this great feeling of solidarity that happens when you do see the other folks of color at those shows. It creates a real positive bond. Sinkane is coming to Iowa City next month and I am going to buy him a beer, whiskey, or Sprite—whatever he drinks, just so he knows he has people supporting him everywhere, even in IOWA.