People Bodies

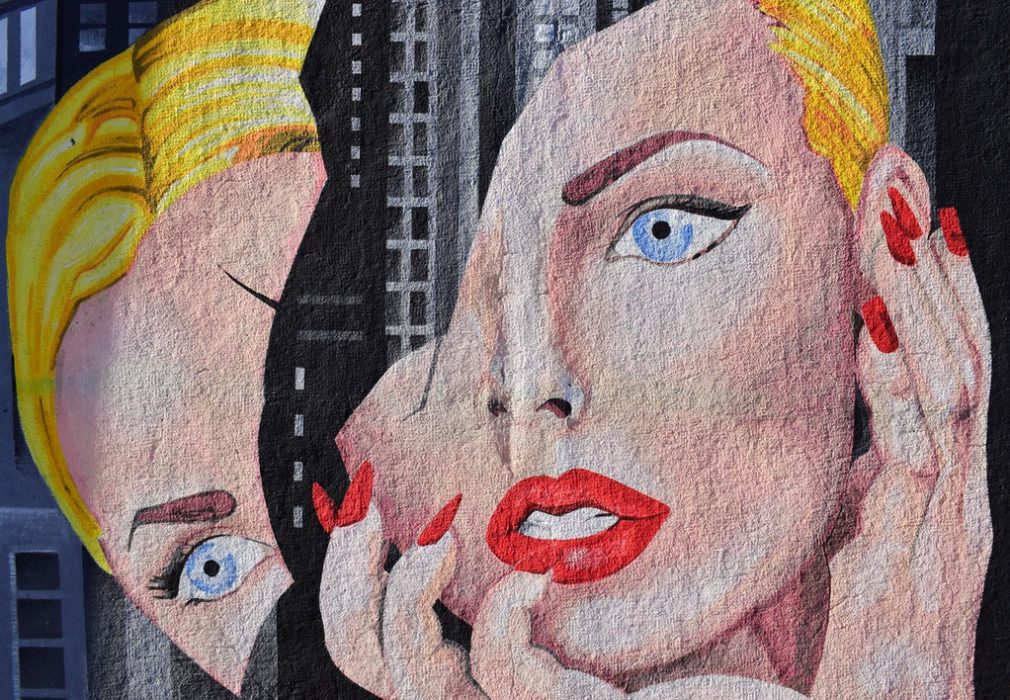

Disfiguration: How to Locate the Soul in Your New Face

Here is how the story of your new face begins.

I knew I was not supposed to move. Pressure churned rhythmically through my lip and out the other side. Each motion finished with the slight tug of a completed suture. Reclining, I stared down the bridge of my nose and caught sight of Becca in the corner of the hospital room. Our eyes met, and hers began to well. I remembered the wedding and the campfire afterward, where I felt jealous of an acquaintance’s perfect babies; I remembered getting in my tent and thinking I was going to bed before the party got too out of hand—and then I remembered nothing else.

The doctor was terse and agitated with me, and I held both my breath and Becca’s eye contact as he finished sewing my face together. The room was quiet with focus and judgment. I held my pose like a statue, knowing I would never be the same again.

This memory from the hospital is lit up with a path of faint stars. There was a car ride with the windows rolled down so the August air could warm us, though I don’t know if it was to or from the hospital. Someone said the word “drunk”—it must have been a doctor or a nurse. Clothes, mine and Becca’s, were covered in blood, as if we had killed someone. And there was a phone call to my mom, during which I struggled to tell her where exactly in Oregon I was, and subsequent missed calls from her as she desperately tried to locate her only child somewhere in the wilderness.

I know that I got drunk at a wedding and afterwards, at the campground where we were staying, got drunker. On my way to the campground’s bathroom, I tripped while running, fell, landed face-first on a rock, and was knocked unconscious. No additional light enters or leaves the dark prism of that night, located somewhere in my memory, somewhere deep in my brain where access may never be granted. I want nothing to do with it.

*

During the fifth century, Greek philosophers had essentially determined that a soul was what distinguished the animate from the inanimate. These theories, though abundant, seemingly all sprung from battle: Because the soul was something you could risk and potentially lose in death, it was thus the mark of the living. A life, and therefore a soul, was yours to keep and protect.

The debate over the soul was a tough one, fraught with disagreement among philosophers. Some argued that wrapped up in this arbitrary gift of a soul, granted to everyone (others would argue everything— plants, animals, oceans), was a behavioral element as well. One’s soul could be judged on how moral it was. So it was debated: Was a soul simply the distinction of a life that could be lost, or did it also apply to an individual’s character?

Imagine not having the science to tell us where a personality came from; imagine it seeming divine. Imagine not knowing if someone’s bad summer was an element of her soul or just a temporary conjuring.

By the end of the fifth century, it had somewhat been decided: A soul distinguished the living from the dead, and the living had a variety of personalities. What continued to be up for the debate was the soul’s location within the body. Was it in the head, or in the heart? Was it somewhere else?

*

Through the tent’s orange nylon, an aura of light filtered in every direction like a warming lamp over hatching eggs. I awoke, uncomfortably hot, sticky in my own sweat. I felt the pulse first in my face, under the skin, taut and expanded, then in my teeth, and finally in my nose as I rolled over. I went to the campground bathroom, where I had stood peering into the government-issue stainless-steel mirror the night before as I tried to get ready for a wedding. Its inability to mirror anything had made applying eyeliner difficult, but now I was thankful that it only showed sparse details.

I saw two broken-off front teeth; my nose with a new horizon; stitches sewing tears back together between my nose and lip, sewing my top lip back together, sewing up a hole in my bottom lip. A layer, maybe several layers, of skin was missing from my chin to my ear on the right side of my face.

For years, there had always been something about my face that made me shy. I had staved off acne with lotions, serums, and antibiotics, and endured nearly four years of teeth-correcting procedures. In your late twenties your body tends to make up its mind about itself, and I was growing into my face—one with skin that was clear and teeth that were straight. I had finally felt comfortable looking straight into a camera and smiling. Now, as I stared into the mirror in the campsite bathroom, gingerly touching the stitches holding my face together and sucking bloody air through new holes in my smile, I worried about the permanence of these new changes.

*

The twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein believed the human body was the best picture of the human soul. Specifically, he argued that meaning is to a word what a mind is to a face. I take this to mean he thought the soul was in the face as a whole, but culturally we tend to chop up features and mine them for their individual significance to our beings. Eyes, especially, draw a soul searcher’s attention.

An oft-repeated adage tells us the eyes are the window to the soul. Studies show that our irises physically change to reflect our desires and impulses. Eyes are the “language of love,” where you can see futures and sunsets, but they can also convey disappointment or deception if, say, someone refuses to take off their sunglasses. All could be lost in losing them. At the same time, a certain mysticism surrounds becoming blind in some stories; losing the sense of vision ultimately leads one to finally see certain things. In blinding yourself, you may offer your eyes to a lover or to God, as saints have done throughout history to prove their fidelity to Christ.

But one’s mouth cannot be removed and offered up like an ear, an eye, or a lock of hair. Sometimes I wish for a recipient of my broken teeth, my lip with a knot in it, my discarded stitches sent in an ornate gold box—someone who would receive the grotesque donation, and grant me something in exchange for it. For better or for worse, a mouth cannot be given away. The new contours of my lips, uneven and alien, have made a fist form inside of me where once there had been an opened palm.

*

The original Greek use of the practice of physiognomy was to assess a personality based on a person’s appearance—usually her face. The practice has long since been dismissed as a pseudoscience, often used to discriminate. Still, today the face carries a lot of weight: A celebrity is the “face” of a brand. Meetings might go better “face to face.” Someone innocent has the “face of an angel.” A woman grows up understanding the secret meaning of the word symmetry —the hideous irony of the observation that Cindy Crawford’s mole somehow made her “imperfect,” and thus more beautiful. As a kid, I would drill a similar beauty mark into my cheek with my mother’s eyeliner, marring myself to be “prettier.”

In the days following my accident, when I couldn’t speak—and the weeks after, when my broken teeth prevented me from indulging in daily baseline human joys like eating meals—up until now, when I feel more comfortable smiling at night, when it’s dark and I know the aftermath of grey teeth and scars and asymmetry will be better hidden—I’ve felt it evident that my soul, at least, extends directly from the mouth. While most of the emotion may come from my eyes, the activity—the smiling, the kissing, the singing and communicating—comes from my mouth.

What is a soul if not, in part, a sum of its body’s actions? Living inside a body, this thing you cannot completely see without a mirror epitomizes the concept of consciousness and self-consciousness. It’s possible to never fully know what the expression on your face is communicating to someone else, or whether your face’s scars are telegraphing a reckless, embarrassing time in your life, despite your soul’s perfect intentions. That summer, it felt urgent that my face heal quickly; that my soul’s main purpose—of just being, rather than ailing or struggling—be clarified at once.

*

Here is how the story of your new face begins:

You spend the ten days while the stitches itch, tighten, and heal wondering how bad it will be. There are so many of them and they are dark, like flies with small, spiky wings.

You spend the rest of your summer and part of your fall with new lips and broken teeth until a benevolent doctor on the Upper West Side fixes your mouth for under one thousand dollars. He is the first person who does not seem to regard the marks on your face as a sign of your problems, proof that you are a disaster.

You learn, at the age of twenty-seven, that nothing about your body is permanent. The fall hammers this home—change this dramatic, this exacting, is something you had once attributed to aging, not injury. You spend the rest of the year bringing up how you used to look to any new person you meet, swiping a circle with your finger around your grey teeth and your uneven lip. It’s always cathartic when they say, This could’ve happened to anyone. You torture yourself for never realizing you had been pretty—symmetrical—before.

You learn the word person came, in part, from a Greek word prosopon, which also meant face, and you will see the path in front of you in which many battles will be fought and the challenge will be to keep your soul intact, starting with each new breaking day when you look in a mirror and confront scars you hate.

Your soul limps and hides with its tail between its legs. Forever, the hardest person to encounter is your mother, the maker of your face. And you don’t trust yourself in the same way that you used to; which is to say, the effort necessary to forgive the soul that allowed your fall in the first place calls for a kindness you’re not sure even exists within yourself.

But things that are different haven’t all been lost. From the inside looking out, you see no scars despite knowing they’re there, which becomes your primary and eternal concern: the self-consciousness of a soul dealing with the borders of a body in its phases of transfiguration. Eventually, you stop telling people about your old face; it makes no difference to them. Mornings still reveal your disfiguring, but they also atone for each day past.

At the very least, scars fade.