People Losing My Religion

From Atheism to the Cosmic

“Finding solace through trusting God became frustrating.”

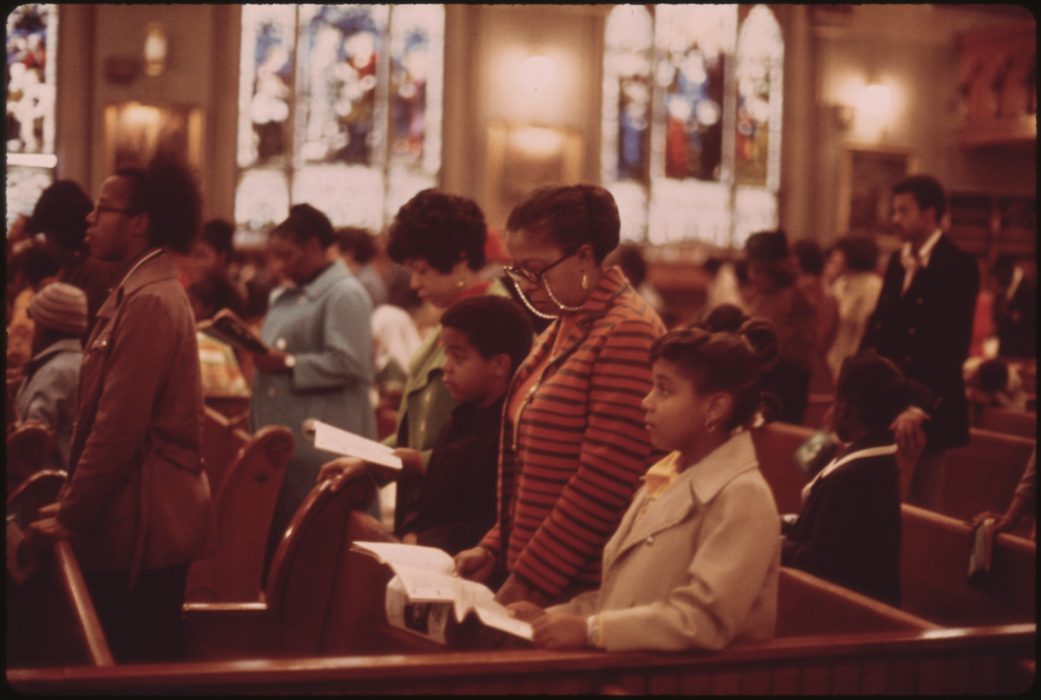

It was Sunday morning and going to church with my mom was inevitable. I had reached the age where spending time with my mother was no longer incentive enough to leave the house per se, and while I could usually talk or cry my way out of Home Depot, Marshall’s, and Dillard’s, church was a harder sell. I didn’t have to go every weekend, but trying to convince my mom I was mature enough to stay at home alone before I was mature enough to not freak out at kids’ Bible study didn’t quite cut it.

We walked into the middle of a service at Zion Missionary Baptist Church—one of many on the east side of Cleveland. The church was simple: gray brick with a brown gable, architecturally similar to something I might have drawn at that age were I not more partial to purple rooftops. This was before the annexes had started to sprout all up and down the street, which was all the better because the one eventually built next to the church had glass block windows, which bothered me; at the time, I was starkly convinced that sort of window belonged only in old ladies’ bathrooms. There were amber-colored blocks making a cross in the middle of each one, and I was still young enough to feel guilty about wondering if Jesus played Tetris.

Service had begun two hours prior. We always went at eleven because sitting still for a few hours was a marathon for a restless child. My mother, though she had an impressive collection of pant suits, did not seem to subscribe as much to the church culture as those around her. She had grown up in rural Mississippi and was about as no-nonsense and anti-establishment as someone could be coming from a tiny town that even McDonald’s didn’t touch until the 2000s. She was deeply committed to God; she was in no way committed to the hierarchy or politics that went on behind the scenes. We shared a certain sense of discomfort with the institution of church.

We diverged where the big questions came into play. Why do people die? Why doesn’t God talk to me like he talks to the people in the Bible? How could a benevolent God oversee the suffering of millions and sadistically demand praise and worship in the face of pain he himself wrought on this earth? But where her questions transitioned smoothly into faith, mine clotted into a growing ambivalence. As my little world expanded, the scope of the universe grew far faster than what scripture could sufficiently explain.

Over time, Sunday sermons started to blur, and I couldn’t stand sitting still for so long with nothing to occupy my young, idle mind, which had learned to grasp neither the meditative nor the performative aspect of prayer. Church was nowhere near as interesting as my Bedtime Bible Storybook, which at least included action, violence, and romance in plain, child-friendly English. The real Bibles at church—leather-bound with leaf-thin golden pages—were cryptic and far less engaging than my Amelia Bedelia books, even if they did involve equally as much unfortunate, literal interpretation of language.

I always clung to my mom skittishly as we looked for seats. Everything grated at my nerves—eyes on my back that probably weren’t there, hats spiraling up like lace towers cutting across the sickly daffodil tint of the vast empty space between us and the high ceiling. Echoes gathered up there: amen , yes Lord , hallelujah , the pastor’s voice running up to Jesus and back before it reached you—a disembodied timbre falling like smoke. I found myself managing an ever-present sense of guilt that I was doing something wrong amidst the adult members’ peace and jubilation.

Eventually, neurosis begot ritual: I counted to fill the time. Intransitive counting, transient counting—I counted nothing into thin air for the sake of sectioning the contents of a racing mind into neat squares: four count, eight count, sixteen count. The longer I went, the more complex the counting became; I descended into it with a determination I could neither diagnose nor control.

One two three four (one)—I was off beat from the melting chords of organ music which were slow, too slow, vibrating the wood on my seat and curling criss-cross with the little lace patterns on my dress.

One two three four (two)—church clap, voices exalting the Lord in vainglorious soprano, boastful alto, crumbling tenor; I can’t tell who’s choir and who’s crowd.

One two three four (three)—locked in, keep going. Yes, Jesus loves me.

One two three four (four)—I kept counting, sticking carefully to sacred rules I couldn’t even articulate: no dangling eights, which felt more like rectangles than squares; no sixes, which zigged and zagged haphazardly between multiples of four; no threes, no thirds, no trinity. Three felt like six. Three felt like six. Three felt like six.

*

I was taking my second year off from college when I started seeing therapist number four. I was on a “voluntary” withdrawal for long-diagnosed health issues—though my leave hadn’t been deemed medical, I needed an official psychological evaluation before I could return. It didn’t make much sense to me, but it would surely be easier than taking a twenty-minute cab ride to a therapist off campus when I sometimes went days without being able to get up and feed myself.

She was the first Black therapist I’d ever had and I was optimistic. I never exactly had a bad therapist, but it was difficult to talk through the overwrought sympathy white therapists often performed when a matter of race or class cam e up, and I had already developed an exhaustion with people cloaking my life in post-racial melodrama in high school. Some therapists give you Lexapro in return for managing their guilt for an hour, at least.

The therapist had a bubbly demeanor and a cheerful, high-pitched voice—she was always decked out in mascara, eyeshadow, and lipstick; she reminded me of the type of church auntie I had taken to dodging in Bible study. The space where we met made me reminisce about the candy lady from down the street who passed away when I was little. Her name was Aunt Cathy, pronounced Aint Cathy due to my mother’s accent, which had stuck strongly to me until elementary school. I’d never been in Aint Cathy’s house, but I always tried to sneak peeks inside as I filled my little fists with butterscotch, strawberry hard candy, and the fruit-flavored Tootsie Rolls I could never seem to find elsewhere. All I can actually remember is that it was dimly lit and carpeted; candy and curiosity made it brim with wonder. The therapist’s office, with its wood walls, carpeted floor, and low lighting, reminded me of elderly Black women and sweetness.

Since I was on leave from school, therapy eventually led to the topic of extracurriculars, clubs, Black student groups. I was officially a part of none. Instead, I usually waded in and out of them sans the sticky commitments, preferring more casual interaction. The sense of displacement I felt as a child in church had metastasized to a sense of displacement in the general world, on both a micro and macro level. Anxiety made every moment a desperate search for contentment and quiet, and prayer helped as little as it had during my younger years. We talked about how and why I felt alienated even from the Black community, which I could easily trace to one core reason: There was, in my arbitrary estimation, about a 90% overlap between the Black student groups and the Black Christian student groups.

I was being a little dramatic, but I probably wasn’t too far off. As a conservative estimate, about four fifths of Black Americans are Christian —not just religious, but specifically Christian. Less than 2% of Black Americans are atheists, with some research yielding numbers as low as 0.8% . It’s almost no wonder my peers constantly assumed I was still Christian; they knew my mother was old-school and southern, and I had grown up attending a Black church, so I understood the cultural references. But I had explicitly given up that part of my identity, and with it, the relief of unconditionally belonging in certain spaces on a predominantly white campus.

I sometimes got invasive questions from Christians who began to suspect me—classmates, community religious leaders, little West Indian ladies on the train platform. The constant questioning made me feel that agnosticism was too weak a means to explain myself; over time, my half-considered ambivalence hardened into an outspoken atheism. The same thing happened with my mother: “Where does God fit in your life?” Annoyed, tired, in no mood to lie, I told her that he didn’t. There was not enough in Christianity to conceptually fill the vast space of the cosmos in a way that felt right to me. She didn’t speak to me for three days; her ability to marathon glare had apparently improved since my youth. I’m not the only one who’s had that experience with Black parents and authority figures . During those three days, the Christian TV increased; my mother even started watching the white pastors, whom I was sure she’d seen as lesser facsimiles of their Black counterparts in preaching style.

I mentioned some of this to my therapist in a self-indulgent tangent about Christian normativity. Christianity seemed as much a posturing mechanism as a religion to me; some instances when people dropped Bible quotes looked no different from when I would pull out a quote from a movie like Friday or The Color Purple . Here’s a benchmark for my identity. This is a tenet of my Blackness. I know the things I’m supposed to know.

The issue of faith returned: “supposed to know” for Christians meant an understanding of the world that accommodated what they couldn’t explain. “Supposed to know” for me was as amorphous as the ways I could find to explain myself: daughter, nerd, Scorpio, agnostic, gamer, atheist, queer, anxious, geek, black, writer, Halloween baby. I constantly tried to make myself so literal that my identity would extend far beyond the endless uncertainty that framed it—the paradox of understanding infinity and trying to conceive all of it anyway. I kept outgrowing my ability to keep calm, and counting didn’t help like it did when I was a kid in church; infinity is not a multiple of four.

My therapist’s face betrayed an odd sort of concern; before I processed what was about to happen, I felt the all-too-familiar wariness of guilt management. I had long since learned to prepare myself mentally for Black women—particularly older Black women—who were not only Christians but self-proclaimed evangelists. It was harder when they were nice about it; I felt bad that they felt bad that I felt bad. Who, I wondered, is served by this guilt?

“Now as a therapist,” she began in a practiced tone, “I can’t recommend that you practice a certain faith. But as a Christian, I don’t want your bad experience with Christianity to make you think it’s always that way. I can’t recommend that you practice Christianity, but I do want you to know we’re not all like that. Religion can be very good for people!”

“So can atheism.”

I didn’t actually say that. I’d developed a habit of fashioning dialogues between imaginary versions of myself and others in which we are inexorably possessed by l’esprit d’escalier: anxiety-fueled wet dreams about a me that is present and quick-minded instead of self-conscious to the point of losing any trace of self-awareness. In reality, I responded with measured politeness. Anything short of panic was theater at that point; since childhood, my neuroses had developed from two-dimensional shapes to fully fleshed out characters in elaborate what-if dramatizations that always made me the hero. Stressful conversations always had a retroactive choose-your-own-adventure sequence that I would latch on to—unhealthy, yes, but also comfortable.

During that time off, I had started to singularly block my mom out before we got to the stressful conversations, particularly ones about religion. I became irritated when the topic of church came up, when she expressed her concern to her friends about me within earshot, when she informed me that my laptop was the mark of the beast. It was something I could never really stand to talk through with her, so I sat to write a letter about it—one that I would never actually send her—just to process it all.

To my surprise, when I sat down to write it, the frustration I thought stemmed from my mother’s religious badgering instead attached itself to a feeling of wishing she’d badgered me more when I was younger. As much as I knew that Christianity was not right for me, as much as I knew that choosing atheism was choosing self-honesty, there was a part of me that wished my sense of purpose could be neatly affixed to faith and fellowship—that church and prayer could rid me of the lingering sensation of being untethered. Wish as I might, the window had closed for Christianity to grant me the sense of belonging I longed for. But as much as I dreaded admitting it to my mom or to myself, I realized that my rejection of religion was no more soothing for my addled mind than trying to embrace it. While I’d acted the part, I realized I was not the stereotypical arrogant atheist; atheism just provided a clearer lens for my confusion. Anything religion could fall short of, I realized, so could atheism.

Where faith and faithlessness fell short, I sought other ways to anchor myself to a sense of belonging, ways that better fit my fidgety mental state; I became very much interested in astrology. Whereas the practice of Christianity became no different to me from pop culture, astrology elevated itself to a form of compulsive meditation: a scorpion tattooed on my ankle like verse; descriptions of what my sign meant relative to every other sign; eagerly parsing the meaning of every single star as it related to me. Where my counting had clear limits, astrology did not. My body was the vertex—the heavenly bodies, rays pointing ever outward: precise angles that covered more and more space as they left me in all directions.

Seven degrees, 35 radians: a sun in Scorpio made being a recluse seem much sexier than Generalized Anxiety Disorder. One degree, 20 radians: moon in Aries made combative streaks and paranoia feel more passion-fueled than connecting them to depression and wildly vacillating self-efficacy. Christianity made me feel dishonest and anxious; atheism made me feel authentic but adrift. Astrology made me the center of the universe. The thought of finding solace through trusting God became frustrating the moment my nervous body moved past the bounds of what my mind could readily control. Atheism felt more like accepting a limitation than stepping into my truth. With astrology, I found comfort without pretending my body wasn’t in a constant state of fight or flight, without pretending my body was not drawn to bodies both like and unlike mine.

When asked, especially by other atheists, I explain that my strong affiliation with my zodiac sign is similar to picking a favorite Ninja Turtle or Thundercat: the same sort of fun as a personality test. The lack of gravitas was undoubtedly what drew me to it. But it would be dishonest to say that astrology, like my nervous habits, doesn’t give me some sort of contentment with my place in the universe. The thought that every person on Earth is radically diverse by a traceable order of years, months, minutes, seconds, miles, gives me peace. On an intellectual level, I understand that this is unsound. I see the irony in rejecting God and trying to lift myself to the cosmic. But my body as synecdoche for galaxy makes more soothing sense than being a lone heathen in a universe so big that one day, I will disappear, utterly. Facing reality in a Black queer body, there is solace in the notion of navel-gazing as star-gazing.