People Bodies

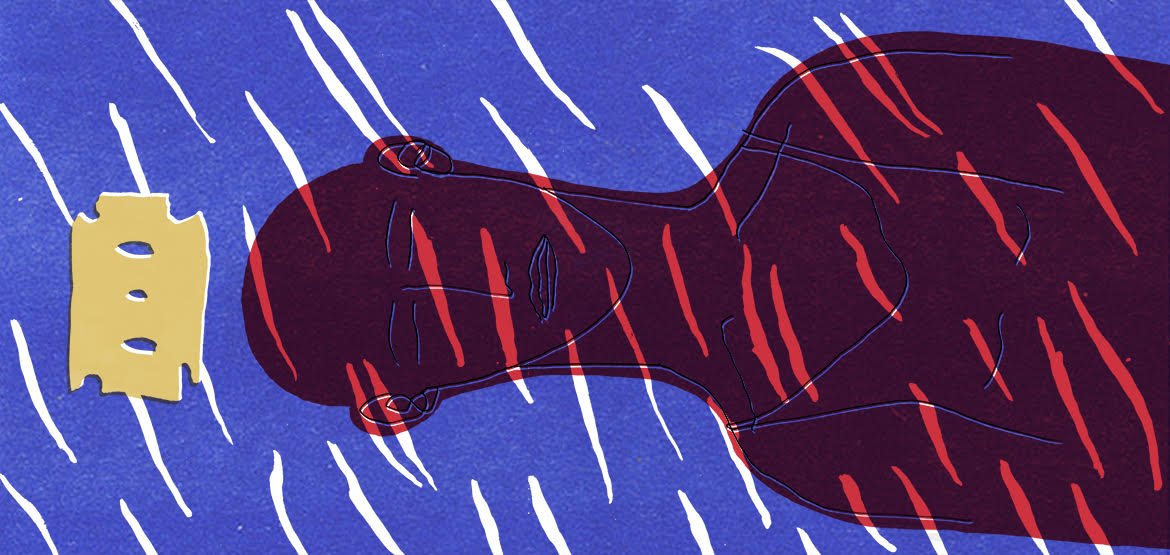

A Myth About Self-Harm

When I cut myself it wasn’t for attention. I cut to feel safe. And to stay sober.

I started cutting myself when I was eleven years old, but I can’t tell you why I did it. Partially because I don’t remember, and partially because I didn’t know myself.

“Be tough.”

It’s something my father often said to me as a child. He wanted me to stand up for myself, to keep on trying, to not doubt my own strength. As I approached adolescence, tough began to slip away from me, eclipsed by messy and out of control .

At first, the shift didn’t show itself in my behavior. For a while, it seemed there was nothing wrong with me. I was tough and I was smart . I ran the fastest on the playground field. I did all my homework. I won the science fair. I never cried when I got hurt. Still, underneath my performance, I sensed a boiling. Sometimes at night instead of sleeping I’d cry in my bed for no reason, confused because I couldn’t identify where the tears came from, frustrated because I couldn’t stop them and because they meant I was weak.

I started to imagine myself as some bad guy in a movie, putting a cigarette out on his arm so you knew not to fuck with him. That was me, but with a knife. I told myself it didn’t hurt and it didn’t. I liked it, and if I bore down into the pain it felt good, something coursing through me electric and alive but also entirely even, not the bubbly tears, not the out-of-control. In the beginning, the cutting was something I did absentmindedly with my pocketknife when I was alone, a secret advantage I had crafted.

It wasn’t until junior high that I gave it much thought. At that age, I loved reading teen magazines: Sassy , Seventeen , YM . I liked to look at the clothes and the cute boys and the makeup. I liked reading the articles about sex, and the “heavier” stories they had in each issue—“I Was Date Raped,” “I Was Anorexic.” It was in one of those articles that I finally recognized what I had been doing for, at that point, three years. It was called cutting. It had a name. Other people did it too.

By then, it had evolved into a hobby. At school, when I was supposed to be having fun with friends, I would think: I can’t wait to go home and cut myself . I had my supplies—at first the pocketknife, and then, after my mother discovered what I was doing and confiscated that, the twisted-off heads of razor blades, wrapped in a scarf, tucked in a box, dried blood encrusted on metal. I liked to light my incense and candles and turn off the lights. I liked to put music on my stereo. I liked the ritual. Once everything was perfect, I cut.

It is hard to separate the things that are wrong with me, because they all feed into each other. I have bipolar disorder, type 1. This was diagnosed my freshman year of high school, a time when my mind had veered wildly out of control. I was hearing things, I was seeing things, and I couldn’t sleep, or concentrate, or control my temper. Sometimes it felt like I was being sucked into an endless pit of evil. Sometimes it felt like I was talking to God. It was exhausting. I suppose it was something that had been in me a long time, the bubbling feeling from a few years earlier. During freshman year, it grew out of control.

The cutting shifted from a hobby into something essential. It was something quick, cheap, and easy that allowed my brain to focus. On something that wasn’t myself, my feelings, or the things that were wrong with me. It settled the thoughts. It allowed me to breathe. It forced me to take a rest, to be still.

There were other things I did that served the same purpose. Not quick, nor cheap, nor easy, but much more socially acceptable. Typical behaviors for teenagers, particularly teenagers with emotional problems. Pot, drugs, alcohol. My school was a wealthy one in California, not far from Humboldt, right next to Tijuana. Just about everything we got was good.

And so I discovered another character trait about myself. As I grew older, I developed a unique ability to turn almost anything into an all-consuming compulsion, something I did not because it brought me pleasure but because it brought me relief.

These are the things I have developed a negative compulsive behavior pattern with over the years: marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, Ecstasy, crystal meth, ketamine, pills (all kinds), alcohol (all kinds), cigarettes, nicotine gum, caffeine, romantic relationships, sex, eating, not eating, sleeping, not sleeping, hygiene practices, lack of hygiene practices, the internet (from AOL to LiveJournal to Facebook), TV shows, reading, writing, working, always being busy, shopping, my makeup, my hair, my clothes, my skin, my nails, cutting.

But maybe even more than an addiction problem, I have a problem with self-destruction. Over the years, I have found so many ways to destroy myself. The drugs, the bad relationships, the smoking. A need to be perfect or, if perfection was not possible, to fail completely, in every small or big thing I did. Suicide (four attempts). Placing myself in dangerous situations. Driving too fast. Overcommitting myself. Obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Cutting.

I don’t know if the cutting is something I am drawn to because it brings me pain or because it relieves it. I don’t know if I am drawn to it because of my compulsion to destroy myself, or if it soothes and narrows the chaos of my mind. I don’t know if it started as a symptom of my bipolar disorder or a result. What comes first. The egg. The chicken. The egg.

The line I heard a lot in high school, in the nineties, from my peers, from the magazines, from the therapists my parents had started to send me to, was that people cut for attention.

I cut mostly on my thighs because it was a place that people don’t normally see. For me, cutting was something I didn’t want to draw attention to. It was a secret.

There was one exception. It was tenth grade. My best friend cut herself too. We spent a lot of time hanging out at this glorified strip mall, the kind that is common in that part of Southern California. One day we were smoking pot in the alley behind the movie theater, with a few boys we sort of had crushes on. One of us had a razor. We started to cut ourselves as the boys watched. They seemed disgusted, not impressed by our desire for pain. But that was the point. It wasn’t something we did to draw in. That time, it was something we did to make us safe. Don’t look at me. Please look at me. Don’t touch me. Please touch me.

The attention is what finally made me stop. Or stop for the most part, at least. It had become common enough in everyone’s psyche to form a cliché: Wah wah, I’m a cutter, I write dark poetry and like the Cure . I didn’t want to be a cliché. I wanted to be tough and I vowed to myself that I would stop.

One night right before I quit, I did Ecstasy with two male friends. One of them sold E, so we had access to an almost unlimited number of pills. The other had an old car, a classic, in perfect condition. We drove around that night, stopping at a party, the canyon, the beach. We took more pills each time we started to come down. The antidepressants I was taking made the E not work that well on me; I was the smallest yet the least fucked up. At the end of the night, we went to a pool, one of the semi-private ones that exist in the luxury condo complexes that are common in that part of Southern California. The lights from the pool made the water and our skin glow green. The pills were making my friends’ eyelids quiver and their pupils blow into discs.

At one point, the two boys decided to roll around on the ground, which was concrete but the polished textured kind that is common around that kind of pool. The Ecstasy had somehow made it feel good on their skin. I tried doing it with them, but it just felt like I was rolling around on the ground. So I took this crappy little pocketknife, one I had bought from Rite Aid for three dollars, from my purse, and used it to cut into my stomach, right underneath my bra. (We had stripped down to our underwear to swim.) They were tiny little cuts. I didn’t want to cause pain; I just wanted to enjoy the sensation.

When the boys saw what I was doing, they seemed horrified. They told me to stop. It made me feel ashamed, and also confused. I didn’t see how it was any different from rolling around on the concrete. They were tiny little cuts. I put my knife away.

I didn’t cut myself for many years. I guess I no longer saw the need to. By then I had gotten into heavier drugs—cocaine and then meth and then synthetic opiates—and was drunk a lot of the time. I had also found a more effective combination of psych meds, so in some ways I was a lot better off than I had been. The nice thing about finding yourself in mental wards at fifteen? There’s not really anywhere to go besides dead or better . I hadn’t died.

When I was twenty-six, I got sober. In the twelve-step meetings I went to, people often described something they called a “pink cloud.” The feeling in early sobriety when the fog lifts, and everything seems wonderful and so great and it is easy to be optimistic about yourself and the future. Things will be better now! I will soon have everything I ever wanted!

This never happened for me.

The first few months of sobriety were, in a word, excruciating. I felt the doom I had been trying to keep at bay since I was a child, suddenly torn wide open like a black hole. I felt jittery and anxious, my mind a noisy tape on loop. It was hard for me to eat. It was hard for me to sleep. Sometimes, it was hard for me to leave my house. I’d ignored the AA rule that says not to make any major life changes in the first year of sobriety, and, twenty days in, had moved across the country to New York.

I remember one night right after ninety days, an important milestone in early sobriety. I was supposed to go to a meeting and accept my ninety-day token. It was a big meeting in Williamsburg, full of cool people in cool clothes who did cool things with their lives. We all joked that it felt like high school, a shared complaint, yet we all went anyway. I had been looking forward to accepting that token.

But that night, leaving my room seemed impossible. I couldn’t even make myself brush my teeth. I didn’t know where to buy drugs in New York but I lived right next to a liquor store and several bars and all of them were calling to me, telling me that they could make the voices shut up, they could settle me, I could sleep and eat and be still. I knew I couldn’t listen. But I couldn’t sit in the noise much longer either.

I went into the bathroom, took the razor I used to shave my legs. I ripped off the head. I peeled apart the plastic and the blades. Into my bicep, I cut a tiny, thin line, forgetting it was still summer and I would have to wear long sleeves until it healed. It had been so long since I needed that type of covering up.

The funny thing about cutting is the shallower you do it, the more it hurts. I was hoping the single cut would be enough, but it wasn’t, so I did another, and another, and soon there was a group of them, lined up neatly like a tally, oozing little beads of blood. The cloud lifted. When my friend called me shortly after, I was able to pull myself together enough to go to the meeting. I accepted my coin. I stayed sober.

Because I stayed sober, over the next two years I finished grad school. I found a relationship, stayed in it, was happy. Later, the comfort of the relationship grew uncomfortable and I did some dumb things and he did some dumb things and one night in our apartment we got into a terrible, ugly fight, the kind that is impossible to recover from. At its climax, he left, escaping to the bar, a luxury I didn’t have. I tried to stop him. A part of me wanted to end the fight but the other part knew if he didn’t leave, the fight would continue, get worse, and that part of me wanted it to. I wanted to completely destroy it: our relationship, our life. So when he left, I followed him, down the stairs, out to the stoop, but his lead was too great and I realized I was now a spurned woman, chasing after a man and it was embarrassing so I gave up, sat on the stairs. I hadn’t thought about the fact that I wasn’t wearing shoes or a jacket, I wasn’t carrying my keys or my cell phone or any money. The door to our apartment building locked automatically after it was shut. There was no buzzer. None of our roommates were home. I was trapped.

I sat on the stoop, cold in the night air, with that familiar feeling of doom. I would need to find a new place to live. I was only partially employed; I didn’t have enough money. I was pathetic, crying and barefoot on a stoop, needing someone to rescue me.

A shard of glass glinted on the street. I picked it up.

I considered the dirtiness of the glass. I considered the possibility of infection. In that moment, a bonus.

I pulled up the hem of my jeans and cut along my ankle. I cut deeper than I had two years ago. To my surprise, the slices didn’t feel good. They hurt.

Right after, I heard a noise, from the chain-link fence that bordered the building across the street, some sort of warehouse. My apartment was once a factory for TVs and technically illegal to live in. There were no trees. The closest thing to nature on that street were dirty pigeons. But on the fence was a raccoon, looking at me, as though it was thinking about what I was doing on that stoop. I looked at it, wondering what it was doing on that fence. It wasn’t the cutting but the raccoon that made me feel safe again.

Later, back in our bedroom, the two of us trying to make up while also acknowledging the futility of it, my soon-to-be-ex noticed the cuts on my leg. The look on his face changed, softened, as though I had made the cuts to show how much he had hurt me. He stopped talking, then reached over and held me. As though the cuts meant more than my tears or my words. I didn’t say anything but I didn’t understand how they were any different from him going to the bar. I didn’t understand how it was any different than the shitty tattoo I would get a few days later, impulsively, as a way to deal with the emotional pain. He thought nothing about going to the bar. Nobody thought much about the shitty tattoo.

I started seeing a therapist twice a week. During that period, I constantly fought the urge to cut myself. This time, my desire was a need to feel tethered. A physical connection to the rest of the world.

One day I asked my therapist a question. I didn’t think it was appropriate but I didn’t know who else to ask. I couldn’t remember the reason we aren’t supposed to cut ourselves. I mean, it doesn’t hurt anyone but us. As long as you don’t do it on an exposed part of your body, it doesn’t affect any other part of our lives. It’s less harmful than drugs. Why not?

She was quiet for a while, and I thought, for a moment, that it was because she couldn’t think of a reason herself. But then she told me, It’s because there are accidents. There’s a possibility of losing control.

When she said that, I remembered an “accident.” I was sixteen, in boarding school, the kind you get sent to because your parents are afraid for you. I was in the shower. I was upset, over who knows what. I started cutting the inside of my forearm. I didn’t do it deep because I didn’t want to get caught; my arm seemed safe because it was already sweater weather. They were just surface cuts, lines thinner than a pencil point. The trouble was, once I started, I couldn’t stop. I got caught. It was too big of an area to hide. When the counselor, a particularly sweet woman named Doris, saw it, she looked as if I had broken her heart. My arm was covered with lines, going upward and across and diagonal. But there was something beautiful in what I had made. A pattern, a quilt. An artifact formed from being out of control.

Sometimes now, while leaning over my students, pointing to things in their papers, my gaze falls across those streaks of scars. I wonder if they ever look at them. If they do, I wonder if they know what they’re from. Their teacher’s past of being messy. Her accidents.

Years later, I remember the expression on my ex-boyfriend’s face—identical to the one my counselor wore, similar to the therapist’s after I asked my question. As though my cutting was for them, an effective way to broadcast my emotional pain. The difference between cutting and drugs? There’s a possibility for accidents and losing control in just about everything we do: alcohol, food, even benign things like driving. But with cutting, even if you do it solely for yourself, even if you do it carefully, eventually it gets owned by other people.

My therapist didn’t supply this as a reason. If you’ve never been a cutter, it’s the kind of thing you can’t possibly know.