Don’t Write Alone Interviews

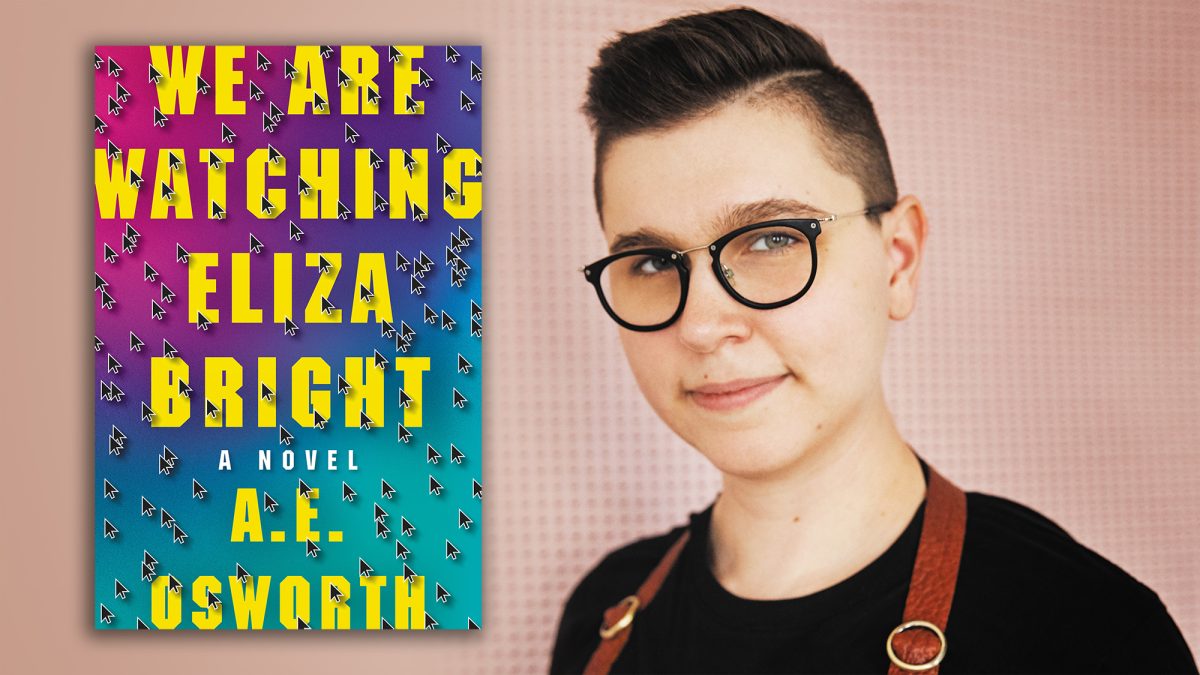

Actions Must Have Consequences: An Interview with A. E. Osworth, Author of ‘We Are Watching Eliza Bright’

“I take real issue with the idea of ‘in real life’ versus on the internet. That’s not a distinction that exists. It’s not honest.”

I’m not certain A. E. Osworth and I made it five minutes into our meeting in person for the first time before we were discussing Dungeons & Dragons. We could’ve touched on any number of commonalities—our respective transitions, our freelance writing careers—but what won out was our mutual love for a tabletop role-playing game where one person, the dungeon master, creates a fantasy world for the other players’ characters to engage in. (Also, there are goblins.)

Osworth usually takes on the dungeon master role, gleefully improvising a story based on their player’s in-game decisions. I wasn’t exactly surprised, then, when their debut novel We Are Watching Eliza Bright offered its reader a similar opportunity to play along, to have some say in how the story’s narrative plays out. Eliza Bright isn’t a “choose your own adventure” so much as it is a “fill in the blanks about your own adventure,” and Osworth offers the reader a generous number of blanks to interpret.

Early on in our interview about their debut, Dungeons & Dragons came up yet again. Osworth and I were discussing Eliza Bright ’s primary narrator, a first-person-plural collective comprised of the most active users of a fictitious subreddit dedicated to discussing the goings-on at a particular video game development studio. I asked where they found inspiration for this collective narrator; rather than naming a foundational novel or author, Osworth mentioned the D&D-based podcast Critical Role , of which they’re a longtime fan. In the show’s early years, they told me, there was what Osworth called a “schism” that resulted in a cast member departing “under mysterious circumstances.”

Over a video call from their place in Portland, Oregon, Osworth recalled that the company behind the podcast released a video about the cast member’s departure that instructed the show’s fans not to speculate: “That was when I popped my popcorn, got on Reddit, and watched perfect strangers talk about these people as though they were close friends.”

The parasocial relationships Critical Role ’s fans had formed with the show’s cast resulted in some listeners developing a wholly imagined sense of intimacy, but one that resulted in very real, intense discussions—ones that were admittedly lower-stakes than what Eliza Bright ’s narrators engage in. To craft their group narrator, then, Osworth pulled from “the imagination—the conditional form—and with it, the disagreements and the texture of a Reddit thread where someone speculates and then someone else comes in with either additional information or conflicting information.”

Over the course of an hours-long video call, Osworth and I talked about Neopets, Gamergate, how the 2016 election impacted an early draft of their manuscript, planning versus pantsing, and, of course, Dungeons & Dragons.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Book cover by Grand Central Publishing

Calvin Kasulke: Can you tell me about the first day you sat down and started writing what would eventually become Eliza Bright ?

A. E. Osworth: I don’t remember the exact first date, but it was an assignment in a class at The New School. And it wasn’t even in a workshop. It was my lit seminar with Shelley Jackson .

Her classes are amazing—this class was called “Strange Worlds, Strange Words,” and it was about the language of a weird world. Aside from the big discussion that we did every class, we had to write two pages in the style of whatever text we had just read.

The text I was responding to was Motorman by David Ohle —in the plot [of Eliza Bright ], there’s no indication that’s what I was responding to—but it had these short, vignetted chapters that jumped around. I’d been doing some light coverage of Gamergate in my capacity as Geekery editor at Autostraddle , and it was on my mind. I actually remember covering it more than I actually did because I was thinking about it so much. I sat down to do the assignment and that is what came out—specifically actually at the very beginning of the book, not the [virtual reality]. The “strange world” that I was occupying was the company. I think it’s a weirder world than the VR one that features superheroes.

I was supposed to write two pages. I wrote thirteen, and then kept going.

CK: Which part of the company did you write about first?

AEO: I remember really clearly writing about the dogs in the company building where the dogs have uniforms—which is actually a real thing, by the way. It’s actually sweet. But I melded it together with what I knew of startup culture and made this strange open-plan office where even the dogs that people bring to work have uniforms.

CK: Can you tell me a little bit about the research you did for this book, for the worlds of both startup culture and gaming?

AEO: I worked in technology, but never for a startup. The way I osmosed startup culture was through my role at Autostraddle, where I was doing things like covering conferences and covering consumer technology and doing explainers about computers . It’s also not particularly hard to osmose because it is so ridiculous, and it’s formulaic. There is a vibe that gets replicated over and over again, including the thing with the dogs—the decisions made about company culture are basically memes. It’s not particularly original, and it’s not particularly careful.

CK: Say more about what you mean by “careful.”

AEO: People who buy into the concept of disruption don’t ever stop to ask themselves the question “Yes, I can, but should I?” So there’s not a lot of forethought in terms of consequences. And we can see that with the political landscape in the US right now, in terms of what social media has done.

The idea of disruption assumes a vacuum that doesn’t exist. And so I wanted to knit together all of the consequences of this pretty inextricably. This is a world that is happening largely virtually, and the consequences of it are supposed to be in-game consequences. They’re supposed to be fake consequences, but they’re not.

I take real issue with the idea of “in real life” versus on the internet. That’s not a distinction that exists. It’s not honest. There are textural differences between those two spaces. Yes, they’re good for different things, but they are equally real.

CK: I want to talk about the process of writing in the first person plural, and also about writing in the conditional tense, because those two things are happening simultaneously in your book and the latter seems to be a function of the former.

AEO: This narrator is not particularly reliable. For most of the book, the narrators cannot see the protagonists. They can see when they show up in the game and they have the invisibility function off. We can see when they receive chats and emails because of the hacking. And they can see them sometimes in meatspace when they’re in a Starbucks or in a restaurant.

They make up largely what happens in their apartments. They make up conversations between them when they’re online and they can’t access the information.

CK: What is your writing process like?

AEO: Unhinged. Let me tell you what I do. I will start a sentence in one chapter and then scroll up and finish a sentence in the previous chapter, and then scroll up farther and then write a whole paragraph in chapter two that I just thought of, and then scroll down and finish the sentence I started in the last chapter at the beginning of that writing session.

CK: That makes me itchy.

AEO: It works for me; I have no desire to change it. I tend to write stories with a lot of interlocking pieces. Actions have to have consequences in fiction. It can’t just be a list of things that happen. It has to be a list of causal things: This happens and therefore the next thing happens.

So when I’m holding a story in my head, I cannot possibly hold that consequence when I’ve written the action, so I skip down to write the consequence and then go back. I have these interlocking pieces, and I don’t care to outline. And I recognize that it makes you want to remove your bones from your body one at a time.

I take real issue with the idea of “in real life” versus on the internet. That’s not a distinction that exists. It’s not honest. CK: There are multiple theories of the case presented over the series of the book—maybe three or four versions of the story that could describe what actually happened. You’ve written a world in which characters go from A to B, but they might’ve taken a lot of different paths to get there, which sounds an awful lot like Dungeons & Dragons. Something makes me think that that’s not a coincidence.

AEO: I am a dungeon master.

CK: Can you talk to me about how that impacted how you constructed this book?

AEO: This is a hot take actually, because there are plenty of popular games where this is not true and people still call them games—the thing that I feel characterizes a satisfying game is that what the players do impact the story. Their choice impacts how the game is going to go forward.

Much like when you’re a dungeon master, you don’t know what choices your players are going to make. You have to have multiple paths for them to go down and be willing to improvise when they choose none of them and go in a different direction that you did not predict. And that is how the narrators operate.

There is one particular place in the book where the collective narrators present different narratives of how things could have gone if the players, the protagonists, had made different choices. They don’t know which choices that the characters made. The whole thing shatters into three pieces, where there’s a big decision that is made, or a big decision that is not made, that they can’t see.

Originally that shatter scene wasn’t in there, but it was the logical conclusion to that dungeon mastering—having multiple paths for people to follow. That shatter reads very much like a Dungeons & Dragons adventure. The thing about the book, though, is that during a game, they pick one. And in this case, there is no one to pick something because it’s a book, not a game.

So the interesting difference between structuring a game and structuring a book is that I had to find some satisfying ways of holding all three threads of possibility for a long time. And the way that that came back around for me, actually, is about computers and not about games. It’s about logic.

CK: What’s meaningful about that distinction?

AEO: The main narrators, these Reddit narrators, function as the OR operator in logic, which is that the code fires if this is true or that is true. But the code fires either way, if either thing is true. And so to keep the story moving I needed to have ways for it to move forward, regardless of which one is true. I know what I think is true, and I will not be confirming which one I think happened, because it doesn’t matter, because the code still fires if any one of them is true.

That was something that I couldn’t describe until way late in the process—the addition of the second collective narrator is when I understood that that’s what I was doing and when I was able to solidify it. The other collective narrator in the story, the Sixsterhood, is a queer art commune that lives in a warehouse in Queens. It’s a much smaller collective than the main one.

Much like when you’re a dungeon master, you don’t know what choices your players are going to make. A thing about queer community is that it largely operates on abundance, and the Sixsterhood is a queer and trans narrator. The way that they operate is that everything can be true at one time. As soon as I figured that out, scarcity versus abundance, it popped into my head that what I have with the Sixsterhood is an AND operator, which is a different thing in logic, where the code fires if and only if all operands are true. And that is how the Sixsterhood works. As soon as I had them to play against, I was able to articulate that that’s how the shatter could work: the Reddit narrators are OR operators , and the Sixsterhood are AND operators .

CK: Speaking of AND and OR operators, do you have experience with coding or programming?

AEO: Very little. The languages that I’m most familiar with are languages that allow me to present myself on the internet: HTML, CSS. I know a little JavaScript. And that’s because I work primarily on the internet. And also because I came of age when people were starting to get the internet in their homes. And so the way to make my world bigger as a kid was to learn how to use the internet.

CK: How did you learn?

AEO: Myspace, Neopets—which I believe makes it into the book. I was always playing around with different ways to communicate with people who were not directly next to me. As a kid, I didn’t have language for queerness, but I knew that I did not belong where I was. So the impulse to make my world bigger by any way I could think of is where those code languages come in.

Also with Web 1.0, the illusion of no consequences was still there for me and for most people. I say illusion really specifically because the internet was a DARPA project . There’s never no consequences about the internet. It’s an instrument of war. That’s how it started. And the industry that drives most of the innovation that we have for it is pornography. I love pornography, but the intersection of sex and violence is what makes the internet go forward.

CK: How does the internet impact how you write sex and how you write romance? Both of which are in Eliza Bright , or maybe not in it, depending on—

AEO: —on who you ask. Depending on what you believe happens in the scenes that shatter apart, there are a couple of iterations of sex in here, some in meatspace, and one in particular in virtual reality.

That one particular scene that features virtual reality sex—which may or may not happen, who knows? The consequences of such an act are real, and therefore it is sex. That is the barometer. The feelings that you get about it are real; therefore, it is sex.

About the shatter plotlines, by the way, my intention with that OR operator is that you could pick any one of them and it would be satisfying, or you could pick something that’s in between them and that would be satisfying too.

CK: Do you think that gives the book a measure of what in games is called “replayability”?

AEO: Yes, I do. But the thing is, books already have that, because we’re different people every time we read them. So you can reread anything and you’re going to take away something completely different from that book than you ever have before. The thing that gives books replayability is our evolution as human beings, which honestly also is the thing that gives games replayability. The replayability is baked into the human experience.