An Unquiet Mind

What If Accessibility Was Also Inclusive?

It’s hard to articulate what it feels like to spend a lifetime being told that you are not allowed. Not always in so many words, but in gestures, in spaces, in thoughtlessness.

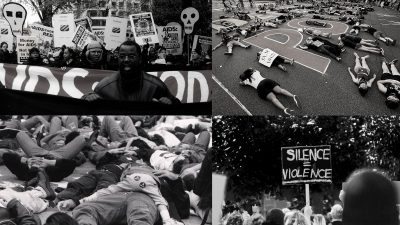

Tired of Dying: Ashes Action, Covid-19, and Protesting Under a Pandemic

When your back is against the wall, dumping your loved ones in the president’s front yard can seem like the only rational response.

The Hands That Haunt Us: When Did Disability Become Consent?

You will remember, in fact, the first doctor who does ask, who says ‘is it okay if I put my hands here,’ gesturing, waiting for you to say ‘yes.’

Why the Label of ‘Gifted Kid’ Isn’t Always a Gift

Here’s a thing about being labeled “smart” as a kid: When there’s a thing you’re not good at, people assume it is because you are lazy.

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Mental Health and Medication

Experiencing a severe reaction to medication taught me many interesting things about the limits of my own body, but also the limits of the world around me.

The Ugly Beautiful and Other Failings of Disability Representation

Those who spend their lives in bodies others deem unworthy grow accustomed to building our own self-worth.

Are We Ever Disabled ‘Enough’ When You Don’t See Our Disabilities?

It is not so much that these things are invisible as it is that people are trained to hide them, and society is conditioned to look away from them.

When Disability Is a Toxic Legacy

Disability is not wrong or tragic or bad, but sometimes it is a symptom of a grave injustice.

Skin Hunger and the Taboo of Wanting to be Touched

How can I say that I fear I’ll never date again without feeding the monster? No one owes me their touch; I am starving for it just the same.

The Beauty of Spaces Created For and By Disabled People

It is very rare, as a disabled person, that I have an intense sense of belonging, of being not just tolerated or included in a space, but actively owning it.