Places Earth

An Island of Trash at the Top of the World

On a remote island north of the Arctic Circle, several centuries’ worth of human-made pollutants have come to rest.

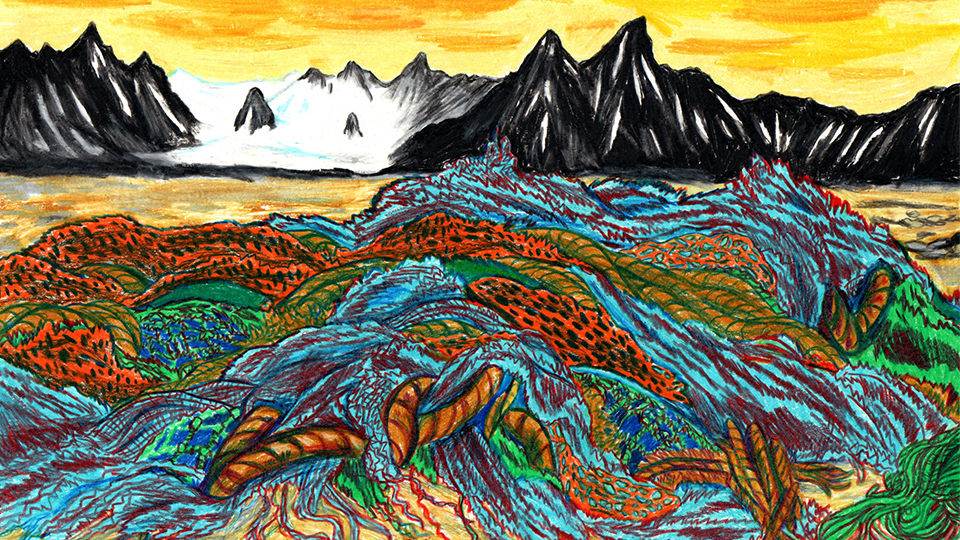

At the 79th parallel, an autumn sun struggled throughout the day to climb above the horizon, throwing brilliant orange and pink hues of dawn and dusk across black-veined mountains. I stood in the cutting Arctic wind on the beach of an island near the North Pole. Behind me lay the remains of a centuries-old whaling station, and all around were the gravesites of men who once plied these waters in pursuit of whales.

On that sunny morning—rare in the Arctic in late October—my eyes were glued to the ground. On the beach beneath my feet, I could see glinting gneiss and shimmering mica schist, rocks formed in extreme temperatures and under enormous pressure over millions of years. Strewn around and atop these rocks were endless strands of green and white plastic fishing net. I bent over to pick up another handful.

*

I visited the plastic-strewn beach in 2017 as a participant in the Arctic Circle Residency, a program with the compelling if vague mission of allowing participants—in this case, thirty artists, brought together on board a three-masted sailing ship for two weeks—to “engage in myriad issues relevant to our time.” As a filmmaker and landscape photographer attempting to document the unfolding environmental crisis, this program gave me the opportunity to visit a region crucial to understanding our rapidly changing world.

Since I was twelve, I had dreamed of visiting the Norwegian territory of Svalbard—a chain of rocky, barren, ice-crusted islands at the top of the world, cut through by fjords with striated mountainsides, jagged glaciers forged over centuries, and waters that are frozen for most of the year. I first discovered it through Phillip Pullman’s The Golden Compass . In the novel, Svalbard is a land of armored polar bears, evil forces, a swashbuckling Texan: a realm of darkness, but also adventure, upon which the fate of the world hung. As I grew older, my interest in Svalbard shifted—now, the landscape seems to stand between the relative stability of the world I grew up in, and the precarious future that lies ahead as our collective environmental breakdown accelerates.

I had arrived in Svalbard familiar with what I thought were the entire set of facts: As carbon dioxide builds to historically unprecedented levels in the atmosphere, the climate is rapidly warming. Changes in the Arctic’s temperature shift weather and precipitation patterns globally; temperature increases in the Arctic lead to rapid glacial melt, which in turn raises global sea levels. If unchecked, this process, known as the Arctic Death Spiral, will irrevocably alter our climate and destroy the conditions that make our lives possible.

Yet even after years of reading about this process, I had not encountered any mention of human-made pollution in the Arctic. I’d assumed that despite the melting glaciers and thawing permafrost, Svalbard would be pristine, free from the poisons that pollute our air, soil, and water around the globe. I was wrong.

*

To the naked eye, the landscape looks untouched, as if it has just erupted out of the earth—all boulder and rock, mountain peaks, and sky. Staring at one of the many moraines that lead from the shores to the mountains above, it appears as if you have traveled backwards through history to a time before humans. In a place that feels utterly non-human, the individual shrinks to nothing. You feel awe and wonder, as well as a profound sense of your own insignificance; an ever-present awareness of the landscape’s cold indifference to your presence.

The austere beauty of Svalbard is deceiving, because one can’t see what lies hidden within. PCBs, heavy metals, plastics, and other toxic chemicals course their way through its air and water. The Atlantic Ocean currents, which keep western Svalbard’s average temperature warmer than the rest of the Arctic, carry large amounts of human pollution into the region from cities and industrial centers further south. Chemicals first spread into rivers and lakes and are then carried into the oceans or evaporate into the air, where they are brought along by the currents snaking their way across the globe. Human-made chemicals like PCBs, which freeze in cold temperatures and evaporate when warmed, eventually make their way north along the planet’s various natural highways. All roads end at the top of the globe, in the High Arctic.

The austere beauty of Svalbard is deceiving. PCBs, heavy metals, plastics, and other chemicals course their way through its air and water. I knew nothing about this when we arrived one cold October morning on the shore of Amsterdamøya, a small island near the top of the northwest coast of Svalbard. Our guides brought us so we could see the remains of an old whaling station and walruses that often gathered around it. The sky was soft blue when we landed, still smeared with dawn’s grey as the sun hid behind the mountains across the bay. A large huddle of walruses lay around the curve of the shore, resting like boulders on the beach. One of them lifted its head to look at us and let out a snort. Only the sound of the wind and our cameras snapping carried across the landscape.

After we explored the remains of the station, a guide asked for volunteers to walk further down the shore to see the effects of pollution on the island. Curiosity at what pollution meant in the context of this otherwise pristine place made me consider leaving the ready-made-for- National Geographic scene around us, but it was guilt that settled my decision. We could only stand in our parkas holding our cameras because we had taken multiple flights from across the globe. My single seat on the flight from New York to Oslo produced roughly 0.90 tons of CO2, enough to melt one square mile of Arctic sea ice. By traveling here, each one of us contributed to the massive emissions that will someday melt the ice around us, likely drowning the land we stood on.

*

It’s not surprising that Svalbard is among the landscapes at the forefront of climate disruption—from its first recorded contact with humans, the island chain has been a source of fuel and resources to be exploited. While the year of its original discovery is not known for certain, the Dutch made the first recorded sighting of the archipelago’s largest island, Spitsbergen, in 1596 while searching for a northeast passage around Russia to the Pacific. By 1612, Dutch, English, and Spanish whaling ships were traversing the seas around the archipelago. That same year, English Captain Jonas Poole reported encountering whales so numerous that his ships nearly had to plow through them. Roughly two hundred years later, the bowhead population of the region would be nearly extinct, slaughtered primarily so their oil could be used to light house lamps across Europe.

After the whale population was all but wiped out, Svalbard became a source of fur pelts for the European market. When that resource was depleted, its mountains were found to hold coal deposits that could fuel an industrial civilization spreading around the globe. In time, Svalbard, along with the rest of the Arctic, would become one of the environments most affected impacted by these extractive practices and the subsequent massive release of energy.

The former whaling station on Amsterdamøya is ringed by sea and mountains. Built in the early 1600s, it could be considered one of the world’s earliest oil factories. From the camp, whalers sailed out to pursue their prey and sailed back with corpses to process into fuel. Although a fort once existed alongside seventeen other primitive buildings, all that remains today are the calcified remains of whale oil that built up around the base of the copper-smelting pots used to melt blubber. Soaked into the sand and gravel of the beach, this formed a kind of cement, with circular imprints marking where cauldrons once sat.

Sailors’ coffins also dotted this shore once, sitting atop the frozen ground with stones resting on their lids to secure the bodies within from scavenging polar bears. “It is observable that a dead Carkase doth not easily rot or consume,” wrote German naturalist Friedrich Martens, who visited Svalbard in 1671, “for it has been found, that a man buried ten years before, still remained in his perfect shape and dress; and they could see by the Cross that was stuck upon his Grave, how long he had been buried.”

Over the centuries, most of these graves have been scavenged for wood or absorbed by the land, and are now no more than small mounds upon the earth. I encountered only one partially intact coffin on a nearby island that served as a lookout post to spot whales. Four long pieces of wood sat on top of moss- and lichen-covered ground, and the stones that once secured the lid lay inside the coffin’s frame, pieces of broken wood beneath. It had taken on the coloring of the rocks around it; death and the land merged into a singular, subtle monument.

From its first recorded contact with humans, the island chain has been a source of fuel and resources to be exploited. Already abandoned due to overfishing when Martens visited in the summer of 1671, the camp was known in Dutch as Smeerenburg—Blubber Town. Throughout the summer season, before the ice and cold of winter forced the whalers south, large copper vats filled with whale blubber slowly cooked down to oil under a sun that never set. The rancid smell of decaying whale flesh and burning blubber would have filled the air as the men skinned their latest catch along the beach and stirred the fat in boiling cauldrons. Thick smoke, burning fires, gagging smells: the hellish work of a haunted species bleeding the earth for fuel. The extracted whale oil lit buildings and houses across Europe, while the baleen and bone threaded corsets and produced knife-hafts and walking sticks.

The oil that formed around the vats and a few petrified pieces of timber are the only artifacts pointing to this primitive oil processing technology. But we didn’t need to know the history to see the human impact on the island. As we followed our guide away from the station, we saw the remains of fishing nets, shampoo bottles, buoys, and so many pieces of plastic ephemera stretched out in piles and patches along the rocky shore. Just as this site once provided fuel for a burgeoning industrial civilization, it is now a graveyard for oil byproducts produced by our own.

*

We walked along the beach, stopping every few steps to bend over and pick up plastic netting that lined the shore, placing it in large Polypropylene bags. At first, we only encountered thin green strands of net poking out of the ground like mushrooms sprouting after rain. Then we came across larger pieces of fishing net—an individual strand might look easy enough to pick up, only we would discover most of its length was buried deep underground, requiring two hands to pull loose. Whole chunks of net, like enormous plastic cobwebs, piled up like seaweed on the shoreline.

As we continued gathering the trash, a painful, frustrating monotony set in. The sheer volume of plastic on such a small beach, on such a remote island, rendered the beauty of the landscape impossible to see. My eyes could only focus on the objects at my feet: water-bleached buoys; a pair of beige high heels with a label inscribed in Cyrillic; black plastic take-out containers; a dented gasoline canister; coils of rope and huge nets. Much of the waste we saw had been produced by fishing vessels, but some, like the high heels, were lonely cast-offs that had roamed the world’s oceans before coming to rest here. Every single piece of net seemed to represent one node in the infinite web of trash our society has created.

Photograph by Brandon Holmes

The further we walked, the more bags we filled, the more mechanical the process became. I lost interest in talking with the people around me. There were only my arms, my legs, the unsteady surface of the beach, the endless trash to pick up. Time slowed as we gathered it into our arms, and a growing sense of pointlessness settled over me. In the same way overwhelming statistics about climate change can induce apathy in some, the act of picking up so much trash made physical a sense of helplessness, even nihilism: We would never be able to clean the ground we stood on.

Yet as the day wore on, even that feeling began to pass. The act of picking up trash, however Sisyphean a task, numbed my frustration. I could sense myself moving past the initial hope and pleasure I’d felt that morning, past the disappointment that inevitably followed, into a place where the act of cleaning the beach was an act sufficient in of itself. While it would be easy to write it off as a feel-good exercise—the waste would pile up again, after all—we were actively choosing to clean up some portion of it together. There was no triumph in this, nor was there any loss. Without hope or fear of a desired outcome that day, we tentatively stepped into the void of environmental catastrophe and did what we could with what we had.

*

History is made visible in the ground beneath our feet, each generation leaving behind its own layer. Societies are often survived only by the trash they amass and the graves of their dead, their stories a mystery to be pieced together from these trace remains.

I try to imagine future archeologists, should they exist, encountering Smeerenburg. What will they make of it? Will they see past those human-made materials—all the plastic I held in my hands, the mounds of melted whale blubber, the remains of coffins—to understand the stories behind them? Will the piles of preserved nets speak to a species driven to extinction? Will they see what we’ve only recently discovered—that the history of oil and fuel production leads from the graves of whales and whalers to our own?